Nike signals that investors don’t get how its business works, and it has a point

For years, Nike has provided investors on Wall Street a unique way to gauge the health of its business. It reports ”futures orders,” which are a tally of goods it has committed to deliver to retailers in the next six months. The program lets retailers buy in advance at fixed prices, and Nike in return gets cash and a glimpse of sales in the months ahead. Perhaps even more than actual revenue, investors have used these orders to make decisions about the company.

For years, Nike has provided investors on Wall Street a unique way to gauge the health of its business. It reports ”futures orders,” which are a tally of goods it has committed to deliver to retailers in the next six months. The program lets retailers buy in advance at fixed prices, and Nike in return gets cash and a glimpse of sales in the months ahead. Perhaps even more than actual revenue, investors have used these orders to make decisions about the company.

But Nike says it’s now changing how it reports those orders, because they no longer offer a full picture of the company’s business.

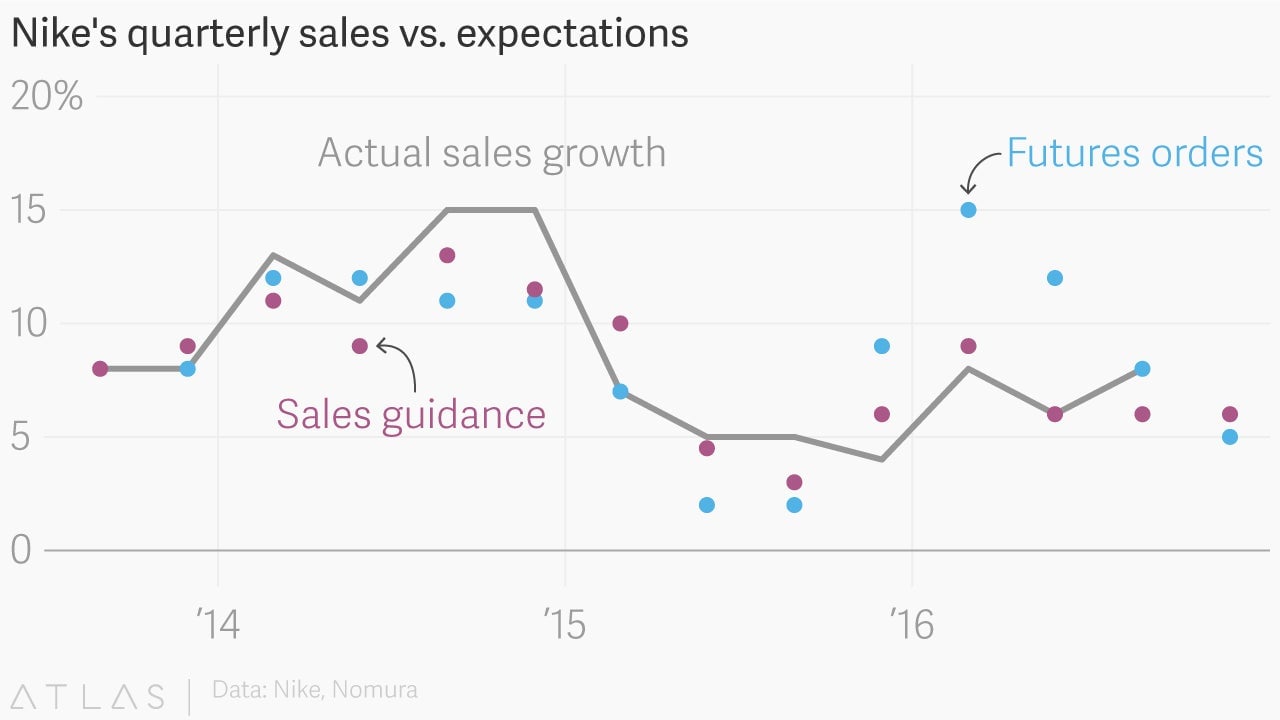

The company is taking a bit of flack for this. Accounting and financial reporting changes are frequently red flags to investors, who often suspect they’re a ploy to mask bad news. And Nike, which is under increased pressure from the likes of Adidas and Under Armour, has had its share of bad news. When it reported quarterly earnings yesterday (Sept. 27), its futures orders missed analyst estimates for the third time in a row. Its orders in North America were up just 1%, the “lowest futures growth expectation for the region since 2Q10,” according to research by Credit Suisse. These are the concerns that have led Nike’s stock to drop 12% this year.

Nike founder Phil Knight created the futures program himself as a way to generate cash in the company’s early days. ”Why not go to all of our biggest retailers and tell them that if they’d sign ironclad commitments, if they’d give us large and nonrefundable orders, six months in advance, we’d give them hefty discounts, up to 7 percent?” he wrote in his recent memoir, Shoe Dog.

But the retail landscape has changed a lot since then. Nike has a network of its own stores now, and the internet allows it to easily sell direct to customers on nike.com and its SNKRS app. That shift has made futures orders from retailers a much less reliable predictor of Nike’s business.

According to an analysis by investment bank Nomura Securities, actual sales tend to track closer to the sales guidance Nike provides to investors than to reported futures orders, with only occasional exceptions. “Sales guidance has been a better approximator of actual sales growth vs futures in all but two quarters since 1Q15 and we therefore fully understand management’s decision to dilute the importance of the metric,” the analysts said.

At its investor day last year, Nike said it plans to grow direct sales from about $6.6 billion in 2015 to $16 billion in 2020. It projects e-commerce sales alone will be $7 billion annually by then.

Retailers are still important to the company, but not in the way they used to be, and Nike believes its earnings reports should reflect that.

Futures orders aren’t disappearing entirely from the Nike vocabulary. Rather than reporting futures as a standalone metric in its earnings releases, it will now just include them in regulatory filings and discuss them on calls with investors, where executives can presumably offer some context.