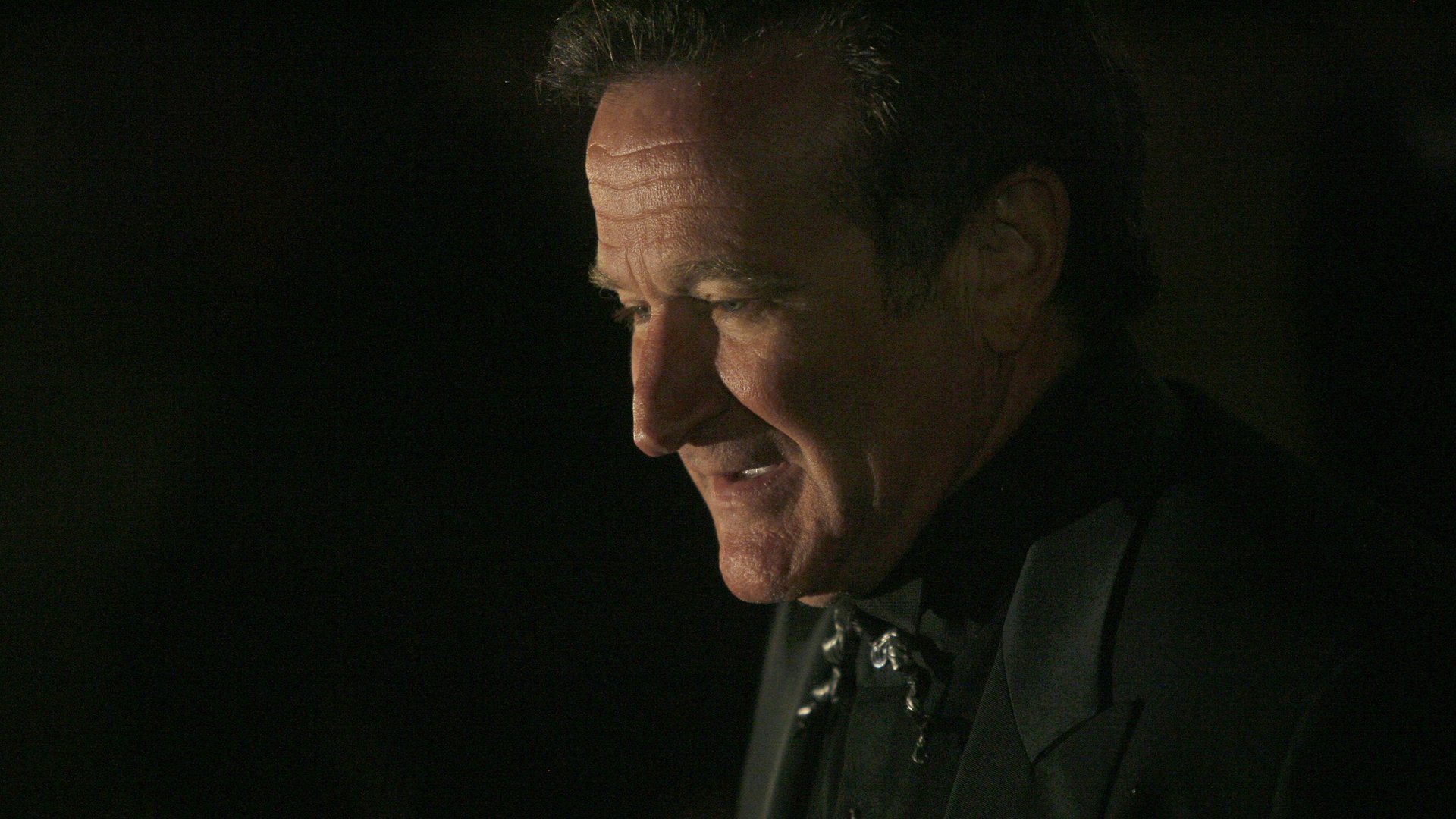

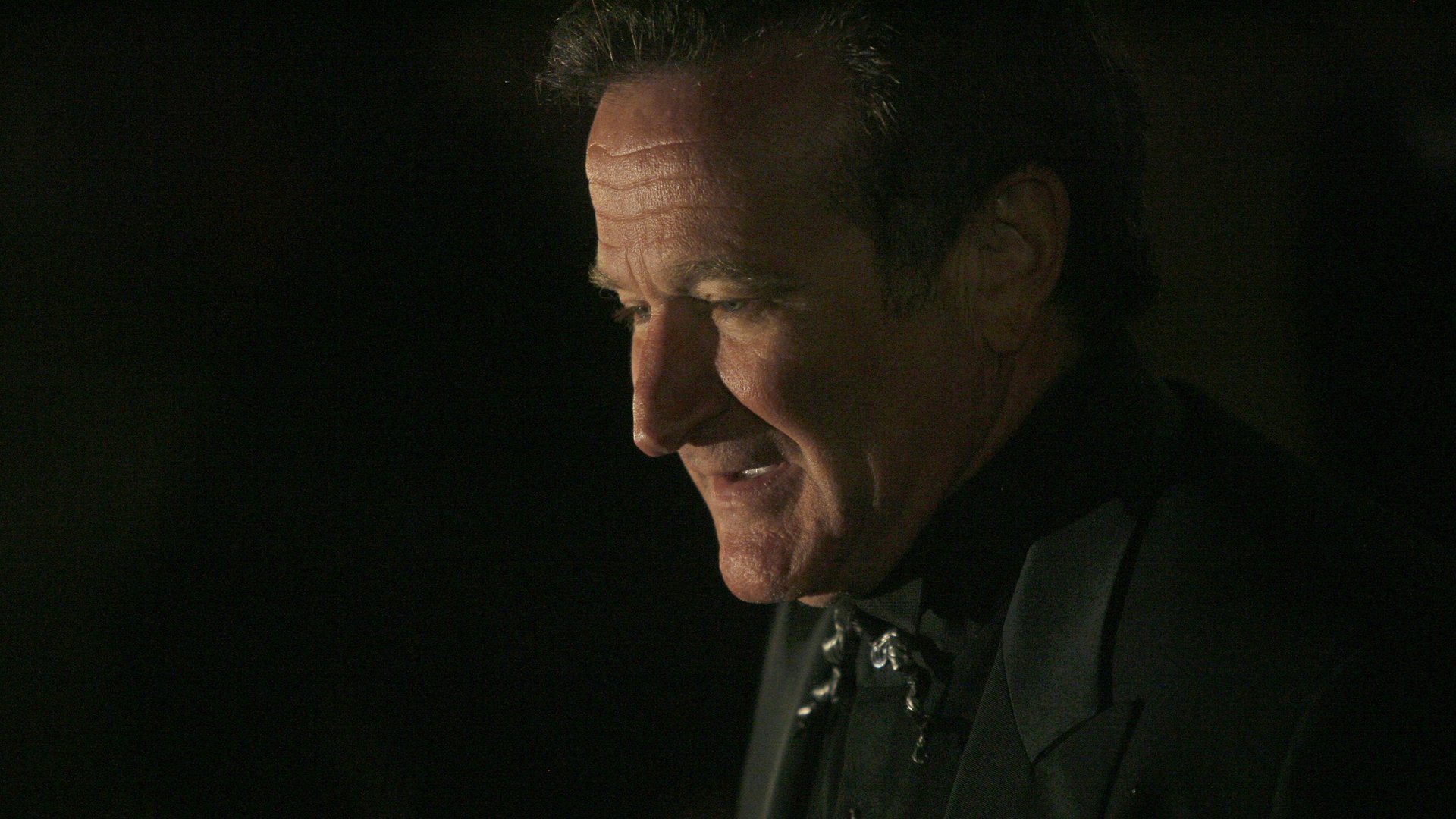

Robin Williams suffered from a common form of dementia that many people don’t know about

Susan Schneider Williams, the late wife of comedian and actor Robin Williams, has penned a harrowing account of how her husband suffered from Lewy body disease (LBD), a form of dementia, prior to his suicide in August 2014.

Susan Schneider Williams, the late wife of comedian and actor Robin Williams, has penned a harrowing account of how her husband suffered from Lewy body disease (LBD), a form of dementia, prior to his suicide in August 2014.

Writing in the journal Neurology, Schneider Williams likened the disease to a “terrorist” inside her husband’s brain. Her husband had been diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease after battling a multitude of symptoms, including paranoia, delusions, insomnia, tremors, and memory problems. It was only in the coroner’s report that the correct diagnosis—and the severity of it—became apparent.

“The mere fact that something had invaded nearly every region of my husband’s brain made perfect sense to me,” Schneider Williams writes. It emerged that “almost no neurons were free of Lewy bodies throughout [Williams’] entire brain and brainstem.” One specialist said it was as if the actor ”had cancer throughout every organ of his body.”

The misdiagnosis of Parkinson’s was not unusual. Lewy body disease is actually an umbrella term for two very similar conditions, dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB) and Parkinson’s disease dementia (PDD). Both are caused by the proliferation of Lewy bodies, abnormal deposits of a protein called alpha-synuclein, in the brain. The main difference is that in Parkinson’s they are concentrated in the brain stem and in DLB they spread to other areas too, according to the Lewy Body Dementia Association in the US.

Together, DLB and Parkinson’s form the second most common form of degenerative dementia after Alzheimer’s disease, and are said to affect around 1.4 million people in the US. Because the symptoms of DLB closely resemble those of Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s, the disease is ”widely under-diagnosed,” according to the association. In the UK, DLB accounts for 4% of all recorded dementia cases, but the real figure could be as high as 10%-15% because of misdiagnosis, according to the Alzheimer’s Society.

People with DLB may show Alzheimer’s-like symptoms of memory impairment and problems with judgment, attention and alertness. Other frequent symptoms include delusions, hallucinations and difficulties with visual and spatial perception. Around two-thirds of sufferers show movement difficulties—a symptom also seen in Parkinson’s disease. Disturbed sleep, including moving around during sleep, and in some cases yelling or acting out nightmares, is also common.

The symptoms of DLB and Parkinson’s are so similar that, according to the Lewy Body Dementia Association, the method of diagnosis is ”somewhat arbitrary”: if a patient starts to have Parkinsonian tremors more than 12 months before showing signs of dementia, it’s Parkinson’s, and if dementia appears before or at the same time as the tremors, it’s DLB. Brain scans can’t reveal the difference, either; often only an autopsy can confirm the diagnosis for sure.

However, while the symptoms may be almost identical, the treatment isn’t. Though there is no cure, various drugs can lessen the impact of these forms of dementia, but certain drugs prescribed for Parkinson’s can make DLB symptoms worse.

Schneider Williams’ research into the condition led her to the American Brain Foundation, where she now sits on the board of directors. Her message to neurologists is to not give up: ”Trust that a cascade of cures and discovery is imminent in all areas of brain disease and you will be a part of making that happen,” she writes. ”It is my belief that when healing comes out of Robin’s experience, he will not have battled and died in vain.”