Everyone’s rushing to drill in the Arctic—but is it worth the money?

From Russia to Alaska, big oil companies are girding to drill in the Arctic Circle, a frenzy ignited by the melting impact of global warming. Or are they?

From Russia to Alaska, big oil companies are girding to drill in the Arctic Circle, a frenzy ignited by the melting impact of global warming. Or are they?

On Sept. 17, Royal Dutch Shell halted drilling offshore from Alaska because of the dangerous movement of ice. In Russia, development of Shtokman, the gigantic natural gas reservoir, has been postponed indefinitely because of cost. ExxonMobil, which has a prized Arctic exploration deal with Russia’s Rosneft, has opted first to drill in a non-Arctic field in Siberia called Bazhenov. And now Total is saying that because of environmental risks, companies should not drill for oil in the Arctic at all (though it says gas, in which the company has some Arctic projects, is fine).

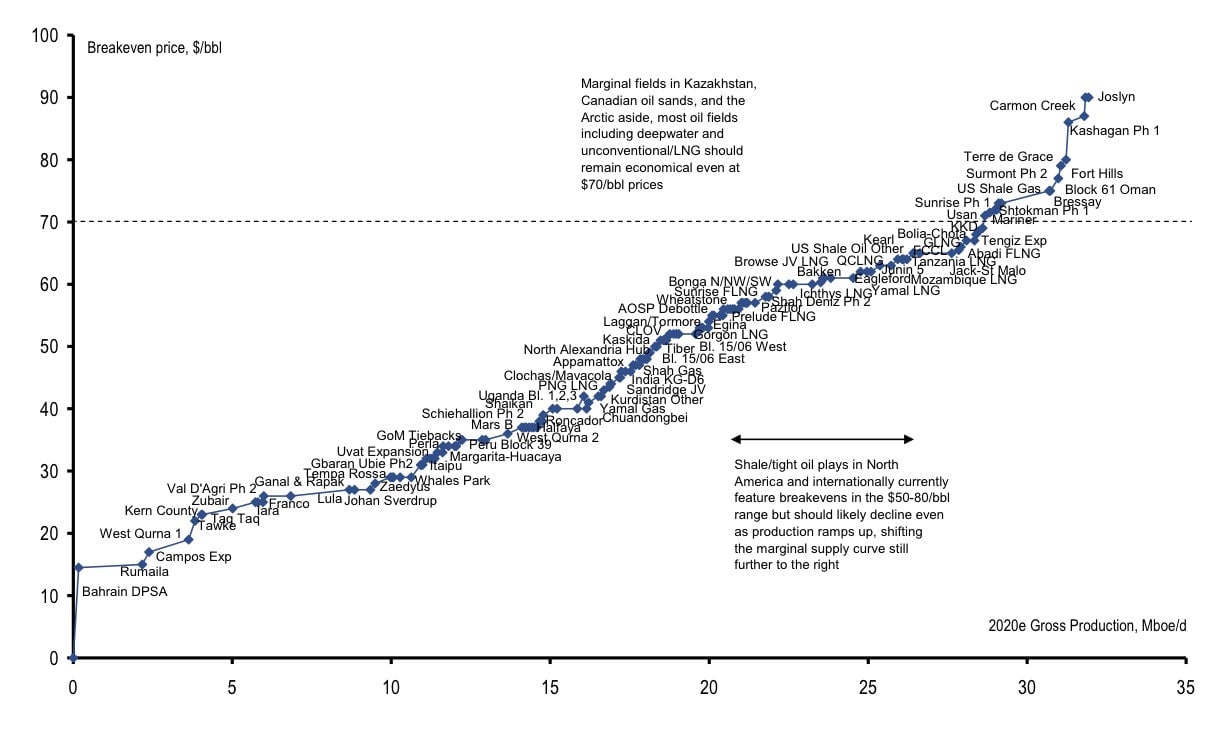

Little is known about the average cost of producing oil or gas in the Arctic, since none of the fields under scrutiny has been developed. But a geologist from the United States Geological Service who evaluated drilling in Greenland estimated that it would require prices of $100 to $300 a barrel and more to extract the larger volumes that are attracting company interest. That’s way above the marginal cost of existing oilfields.

Meanwhile, a boom is under way in less-expensive drilling locales—Mozambique, French Guiana and Angola among them, where break-even production costs are less than $70 a barrel. Given that plans for this drilling stretch into the 2020s, activity in the Arctic is likely to be far in the future.