A quarter of all Nobel prizes in medicine have been for research on the smallest unit of life

It’s not easy to make a 12-year-old read a science textbook. He has friends to hang out with, video games to finish, and pranks to plan. And, yet, when I heard the magical tales of a whole new world that existed inside the world I lived in, I was hooked. The person who hooked me was a biology professor, and the new world that enchanted me belonged to the smallest unit of all life: a biological cell. It created in me a strong love for all of science and even gave me the resolve to get a PhD.

It’s not easy to make a 12-year-old read a science textbook. He has friends to hang out with, video games to finish, and pranks to plan. And, yet, when I heard the magical tales of a whole new world that existed inside the world I lived in, I was hooked. The person who hooked me was a biology professor, and the new world that enchanted me belonged to the smallest unit of all life: a biological cell. It created in me a strong love for all of science and even gave me the resolve to get a PhD.

Cell biology is a crucial part of medicine. Nearly a quarter of all the Nobel prizes for physiology or medicine—including this year’s, awarded yesterday to Yoshinori Ohsumi of the Tokyo Institute of Technology—have been for research in this field. So what makes the cell so special?

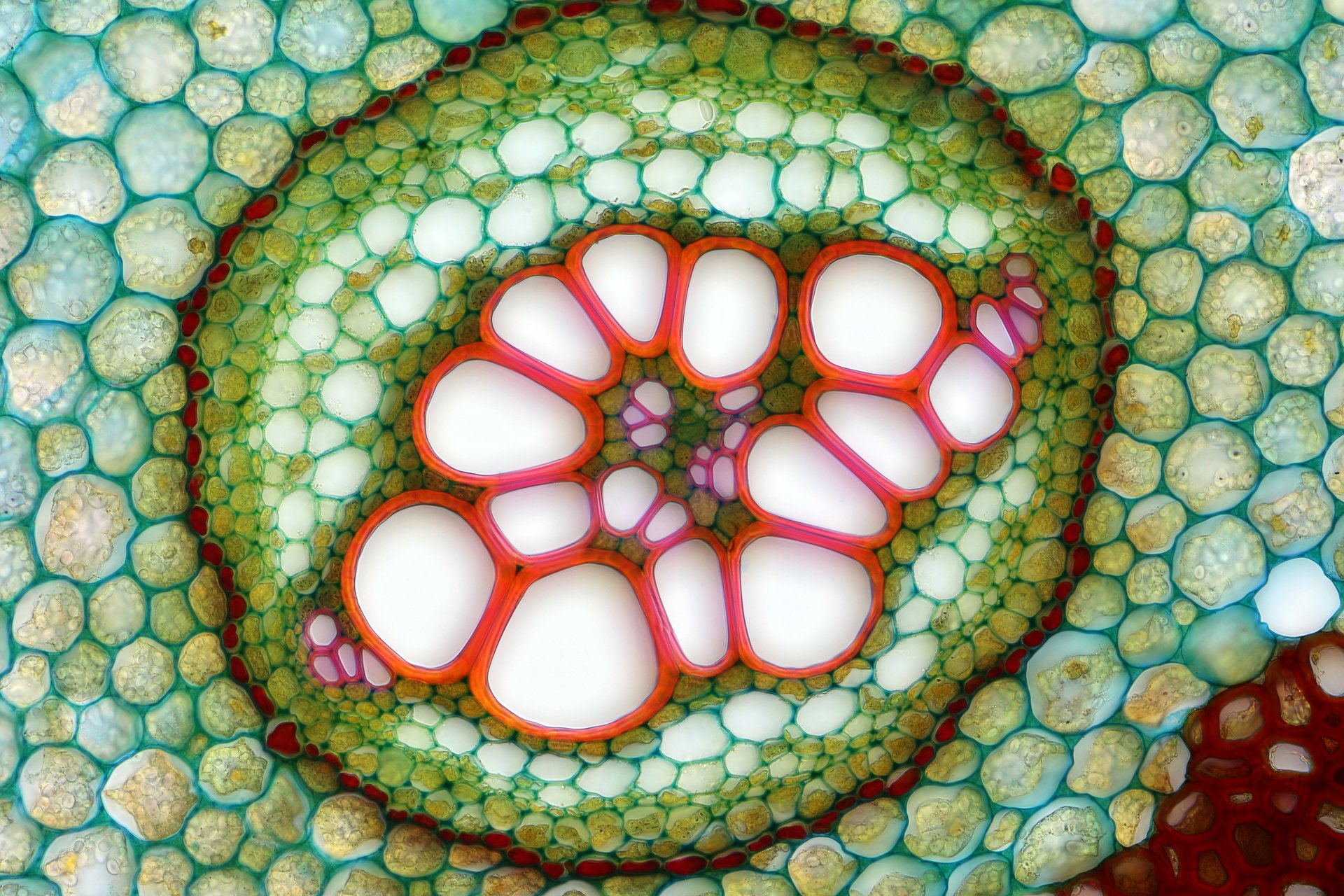

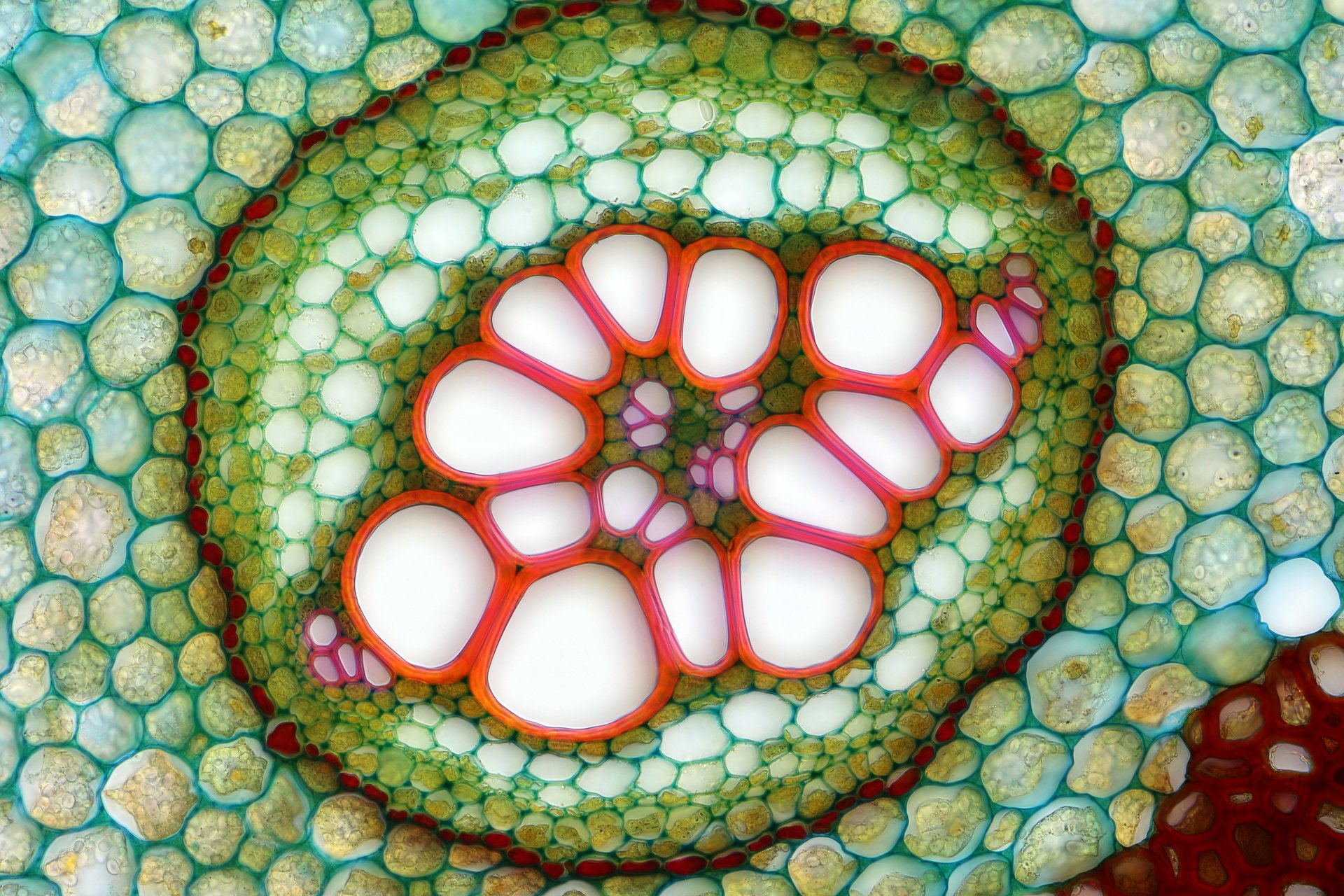

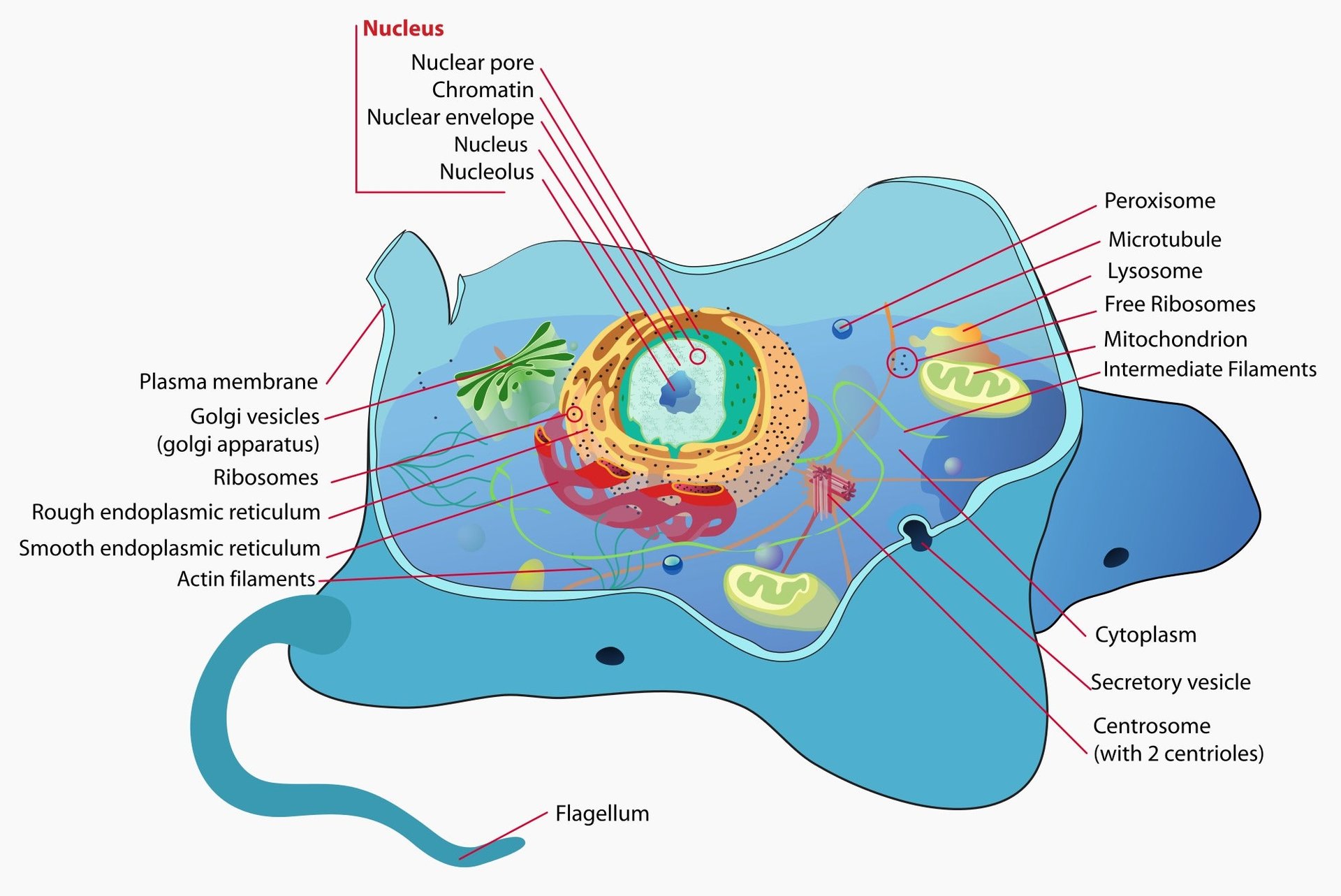

Each cell in the human body is ten thousand times smaller than the body itself, and yet it is just as complex. Your body has organs; a cell has specialized organelles. You have a brain; cells have DNA which determine how they function. You have lungs; cells have mitochondria which provide essential energy molecules. You have blood; cells have cytoplasm which ensures the flow of all crucial elements. You have bones; cells have a cytoskeleton which holds the structure firm but keeps it flexible. You have skin; cells have membranes that keep it contained and allow for transportation of crucial fluids. And so on.

Another way to think about the cell is to compare it to a pencil factory. Billions of pencils are made every year. But, as immortalized in a 1958 essay by the economist Leonard Read, the process to make each pencil is incredibly complicated. The wood is harvested, the graphite is mined, the lacquer synthesized… and so on till all those ingredients come together in an orderly manner to produce one of the most common commodities of modern life.

Now consider one particular type of cell, the pancreatic islet. Some 3 million of them exist in every person’s pancreas and each of those cells creates the hormone insulin, which regulates the amount of sugar in our blood. When the islets don’t work properly, you get diabetes. Each islet is like a single pencil factory, assembling insulin molecules from a variety of different chemicals that the body sources from diverse raw materials in the food you eat and the air you breathe. An insulin molecule is many times more complex than a pencil, and in a healthy pancreas the islets produce trillions of them each day without any mistake.

Each cell in the human body is a highly sophisticated factory of this sort, and they all work perfectly in tandem (most of the time) based on simple instructions. They also produce very little waste, relative to the complexity of work they perform. How they achieve that is the discovery for which Ohsumi won the Nobel: using equally sophisticated systems, present in each cell, to break down and recycle waste matter.

There are, of course, many other such magical tales science has to tell: from the Big Bang to quantum computers. And, yet, none of those tales are as accessible as the world of the smallest unit of life. All you need to delve into cell biology is some water from a pond or a river and a $1 microscope.