The secret to a higher salary might be to ask for nothing, but it only seems to work for men

I read Brooke Allen’s provocative advice for job seekers (“The secret to a higher salary is to ask for nothing at all”) with relish. Who doesn’t love a good counter-intuitive argument? And I’m a big fan of negotiation tips that cultivate mutual empathy and win-win outcomes. So why was I left with a nagging feeling that he’d neglected something?

I read Brooke Allen’s provocative advice for job seekers (“The secret to a higher salary is to ask for nothing at all”) with relish. Who doesn’t love a good counter-intuitive argument? And I’m a big fan of negotiation tips that cultivate mutual empathy and win-win outcomes. So why was I left with a nagging feeling that he’d neglected something?

Because he failed to mention two of the critical conditions required for his advice to work:

1. You need to explicitly define the work that’s being done.

2. And you need to agree, at least roughly, on the financial value of that work.

These may seem like absurdly obvious conditions. But bear with me, because they matter greatly—especially for women.

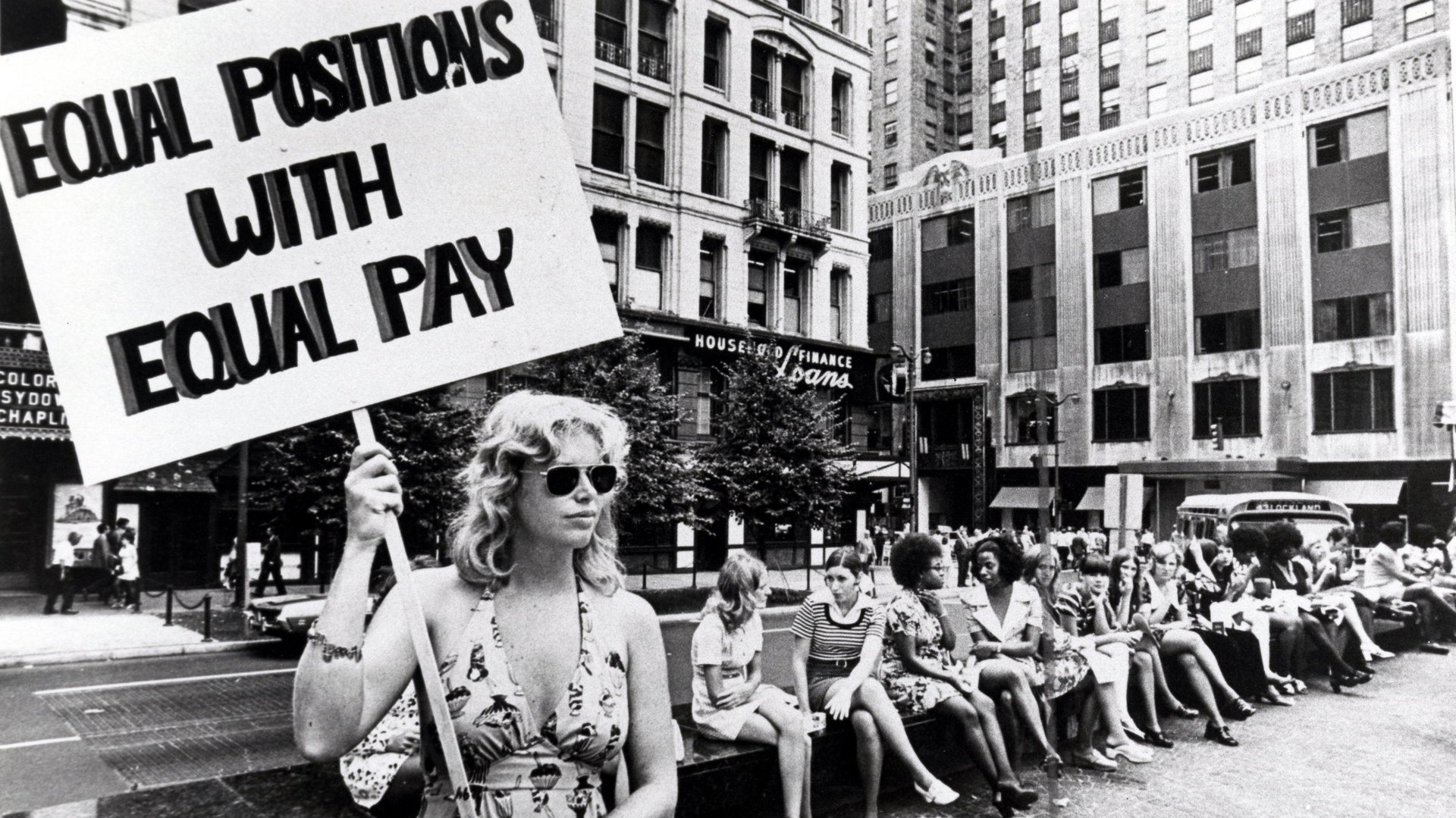

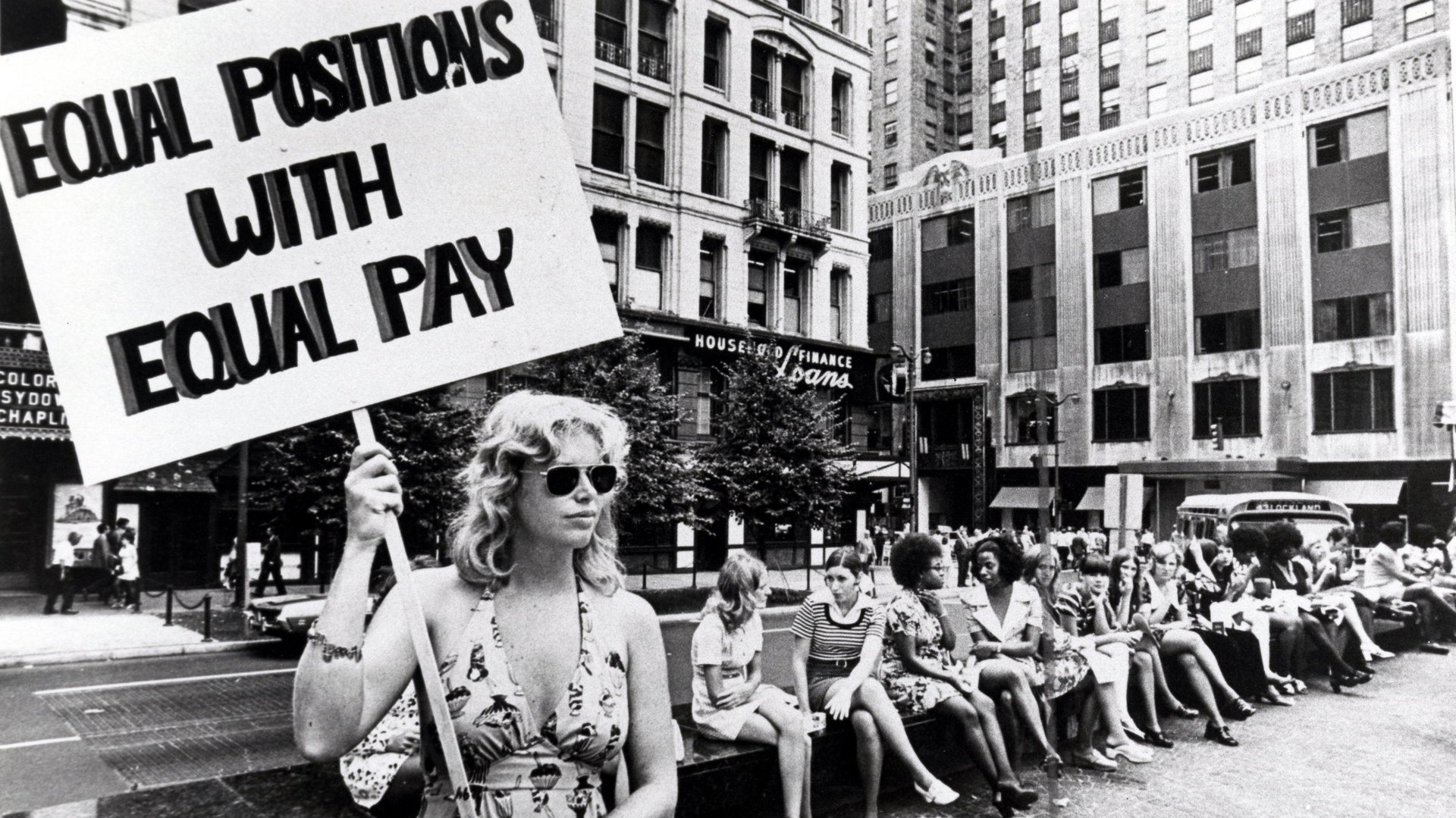

Women, according to research by Linda Babcock and Sara Laschever, don’t typically negotiate with employers over compensation. Joan Williams of the Center for WorkLife Law suggests that this is because women are stuck between a rock—negotiating and being perceived as overly aggressive—and a hard place—not negotiating for the sake of maintaining a “nice” image and losing out on earnings. Williams delicately sums this up with, “Women don’t negotiate because they’re not idiots.”

With men still out-earning women by a significant margin (by anywhere from 7-23%, depending on how you crunch the numbers), the research suggests that the two most significant contributing factors to the wage gap are lingering gender discrimination (both overt and unconscious) and negotiation skills. If the former is arguably beyond women’s control, the latter surely isn’t—though it means overcoming some serious cultural conditioning.

What I’ve noticed is that women, as a group, have a tendency to perform invisible work in the workplace, because that same tightrope Williams describes applies to self-promotion: If you talk too much about what you’ve accomplished, you lose your “nice girl” status and get filed under “bitch.” Add that forced-humility conditioning to our self-critical undervaluing of our own skills, and you have a recipe for significant discrepancies between how men and women describe their past performance, as well as their future potential.

This doesn’t bode well for Allen’s advice crossing the gender divide. Here’s why:

His thought-provoking and high-minded proposal assumes that both parties have the same picture in their heads of the job description. And from what the research shows about women, we are likely to undersell our skill level and experience, and over-deliver once we’re hired (because we turn out to have far higher expertise than we give ourselves credit for).

Women ultimately don’t get rewarded for several reasons:

1. We aren’t always strategic about what and how we give. We tend to be quick to pick up slack on grunt work and things that aren’t in our job descriptions, to keep the peace and make the work environment more pleasant.

2. The aforementioned aversion to tooting one’s own horn—it’s frowned upon in women more than men.

3. We don’t tie our “giving” to business objectives. (This is a different angle on #1.) Brooke Allen’s advice is basically to approach the employer with the attitude, “I don’t make money until you make money.” That’s a pretty aggressive approach in some ways because it means you’re playing a high-stakes game and you’re gambling that your work has a measurable impact on revenues.

If I were an employer faced with a candidate who under-promised on their abilities, I’d be hard-pressed to assess their value at the same level as someone who was a better salesperson. Odds are that I’d offer the humble applicant a lower wage than the more confident one.

The million-dollar question is, of course: Would Allen have received the same, generous offer if he’d been a woman, a person of color, or someone with a disability? I doubt we’ll ever know the answer to that. But we can ask ourselves what marginalized groups can take away from Allen’s advice, and I think it’s this:

If you want to increase your earning power, you’d better learn to define the exchange with prospective employers in a way that clearly communicates your value.

That’s not going to magically erase the wage gap—there’s still that pesky cognitive bias problem to solve–but it might at least put us in a position where if we’re doing things for free, we aren’t also doing them invisibly.