“It was seen as distasteful. Maybe that’s why David loved it.”—Inside Bowie’s private art collection

David Bowie might be gone, but his spirit lives on through the artworks he collected, which are currently traveling the globe.

David Bowie might be gone, but his spirit lives on through the artworks he collected, which are currently traveling the globe.

A long-running retrospective of his collection and his artistic legacy makes its way to Asia in coming months, and hundreds of works from his private collection will go on sale in London in November. Sotheby’s offered a glimpse into that private collection in Hong Kong last week, displaying 35 out of the 350 artworks, estimated to be worth between £9.8 million and £14.3 million ($12 million to $17.5 million).

Beth Greenacre, gallery owner and curator of Bowie’s private art collection for 17 years, was on hand to explain how the private collection reveals a side of Bowie beyond his memorable stage presence.

“I always think of David as a social and political historian,” she told Quartz. “He always looked backwards to understand his and our current position in the world, and then looked forward to predict [the future],” said Greenacre, who met Bowie in 1999 when she was fresh out of university. “He was inquisitive, well-read and intelligent.”

The works in his collection raise the existential question of mankind, which Bowie also questioned through his music, she said.

Bowie developed his love for collecting art very early on. According to Frances Christie, a senior director at Sotheby’s who is handling the auction of Bowie’s art collection, the late star used to bid for artworks in the bidding room himself, rather than sending a buyer, a sign of his passion for collecting.

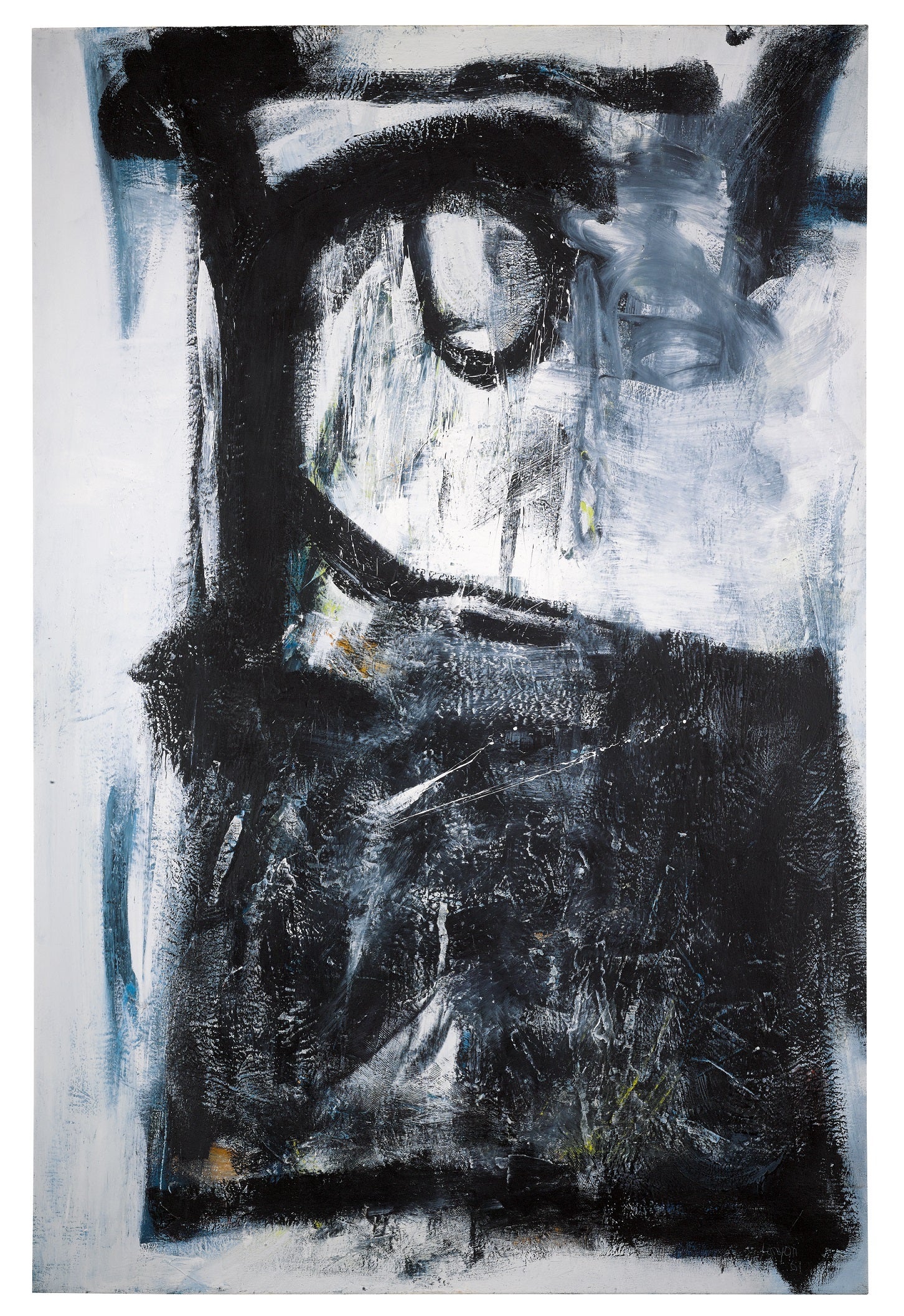

The collection on sale contains a diverse range of artworks and objects, from Frank Auerbach’s sculptural oil painting Head of Gerda Boehm (1965), which used to live in Bowie’s apartment, to paintings by Jean-Michel Basquiat, to obscure furniture and design objects. (The entire catalogue of Bowie’s art private collection can be viewed online.)

Bowie told the New York Times in 1998 that “art was, seriously, the only thing I’d ever wanted to own. It has always been for me a stable nourishment.”

Among his pieces is Ettore Sottsass’ wooden shelves known as “Carlton” Room Divider designed in 1981. Greenacre says that when the design emerged, it was considered unfashionable and being looked down upon. But Bowie took it home.

“Today, there’s a revival in terms of academic interests in it. David, as throughout his artistic and creative endeavor, was ahead of everyone else,” she said. “It was a post-modern piece, borrowing concepts from different sources. It was seen as distasteful. Maybe that’s why David loved it.”

“Via his music and collecting, he questioned any given moment in reality. A lot of artists [in the collection] were very avant-garde. They were questioning questioning the given reality and the fractured world,” Greenacre said.

Witness (1961), one of the three paintings that Bowie loaned to Tate St Ives for a 2011 retrospective of the late British artist Peter Lanyon, has a special connection with the star, says Greenacre. While Bowie was always on the edge throughout his artistic and creative career, Lanyon was physically putting himself at risk. The curator said Lanyon’s bleak painting was inspired by the artist’s experience in the sky on a glider, a super-light aircraft that typically has no engine. “He was putting himself on the glides. He was killed in a gliding accident few years [1964] after the painting was done,” she says.

Greenacre declined to reveal the exact size of Bowie’s collection, but said Bowie’s estate retained a number of significant works. The late star was already planning to disassemble the collection before he died of cancer in January, she added. “David only saw himself as a custodian of the works. He wasn’t about ownership. He would just hope other people to enjoy the work after he had done so,” said Greenacre, also a long-time friend of Bowie.

Greenacre was introduced to Bowie in 1999 through the collection’s previous curator Kate Chertavian soon after she graduated from The Courtauld Institute of Art, one of the world’s most prestigious schools for the study of art history. She became the collection’s curator in 2000 and worked on numerous projects with Bowie, including Bowieart, an online platform supporting young artists.

“Just working with David and having conversations with David was enough to change you. You were constantly learning because he was so well-read. He was so intelligent that he would make connections with things. You would go in having conversation with him on an artist or an exhibition and suddenly it would spark a connection with something completely disparate but logical in David’s mind,” she recalls.

Traveling was important to Bowie, says Greenacre, and Asia had a special place in his heart. He had close ties to Hong Kong, which were highlighted during the viewing here.

Cha Na Tian Di, Bowie’s first and only Chinese-language song released in 1997, was dedicated to Hong Kong shortly before the handover of the city. The song is a Mandarin version of Seven Years In Tibet from album Earthling, and the project was developed in Hong Kong with the chorus “You have my blessing, the world is merely a glimpse of time” written by Hong Kong lyricist Lin Xi.

His performances in Hong Kong in 1983 and 2004 are well-remembered, and his music influenced generations of musicians in Asia.

Greenacre said believes such notion will make Bowie’s art collection appealing to an Asian audience.

Bowie also spent a lot of time in Japan, Greenacre noted, and the Victoria & Albert Museum’s touring exhibition “DAVID BOWIE is” will bring the late star back to one of his favorite countries. That show’s only stop in Asia will be at Warehouse TERRADA in Tokyo on January 8, 2017, Bowie’s 70th birthday. The exhibition highlights more than 300 objects ranging from music, rare footage, costumes and collectibles from the David Bowie archive, which Greenacre works with closely.

Follow Vivienne Chow on Instagram @missviviennechow and Twitter @VivienneChow