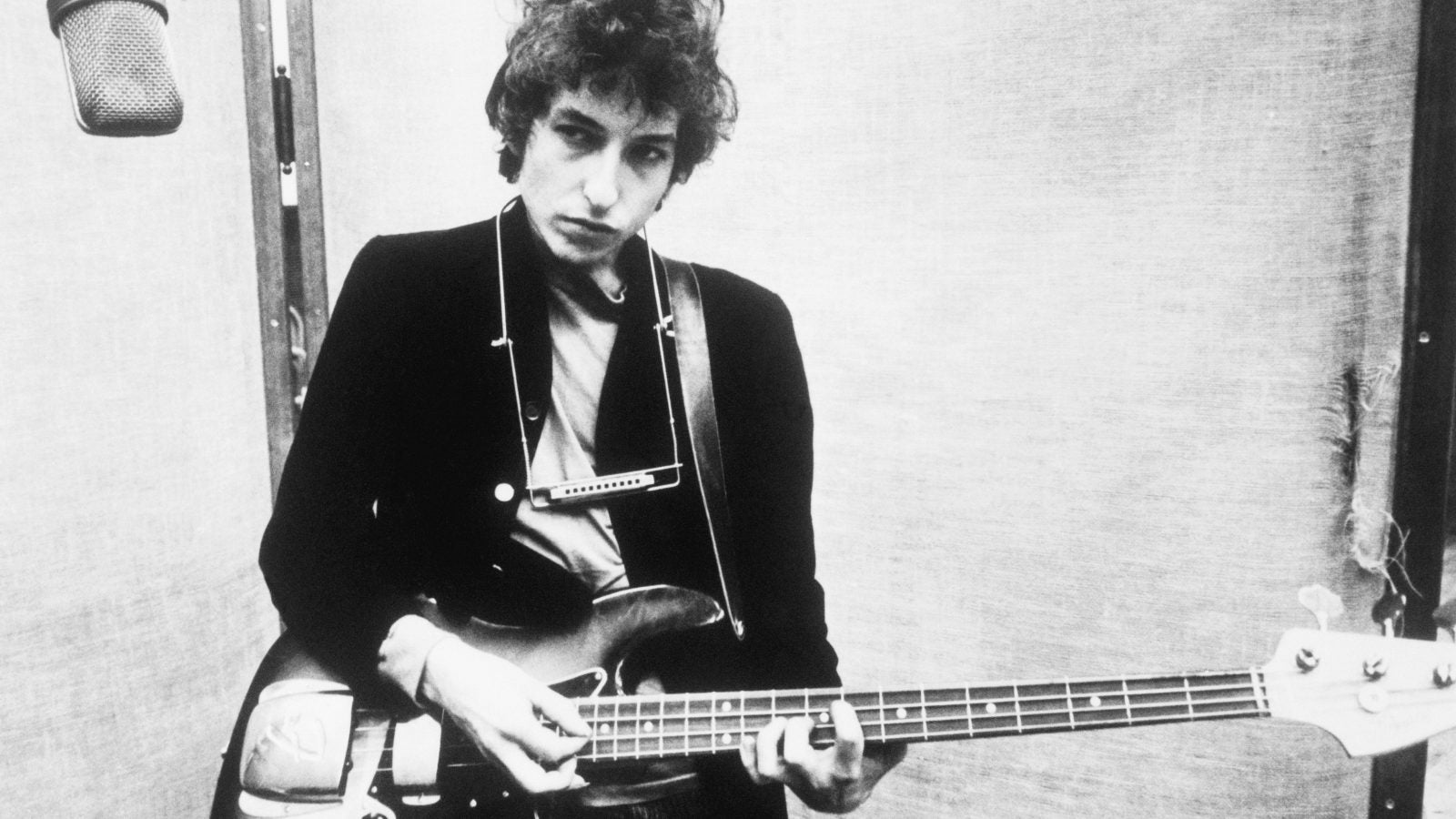

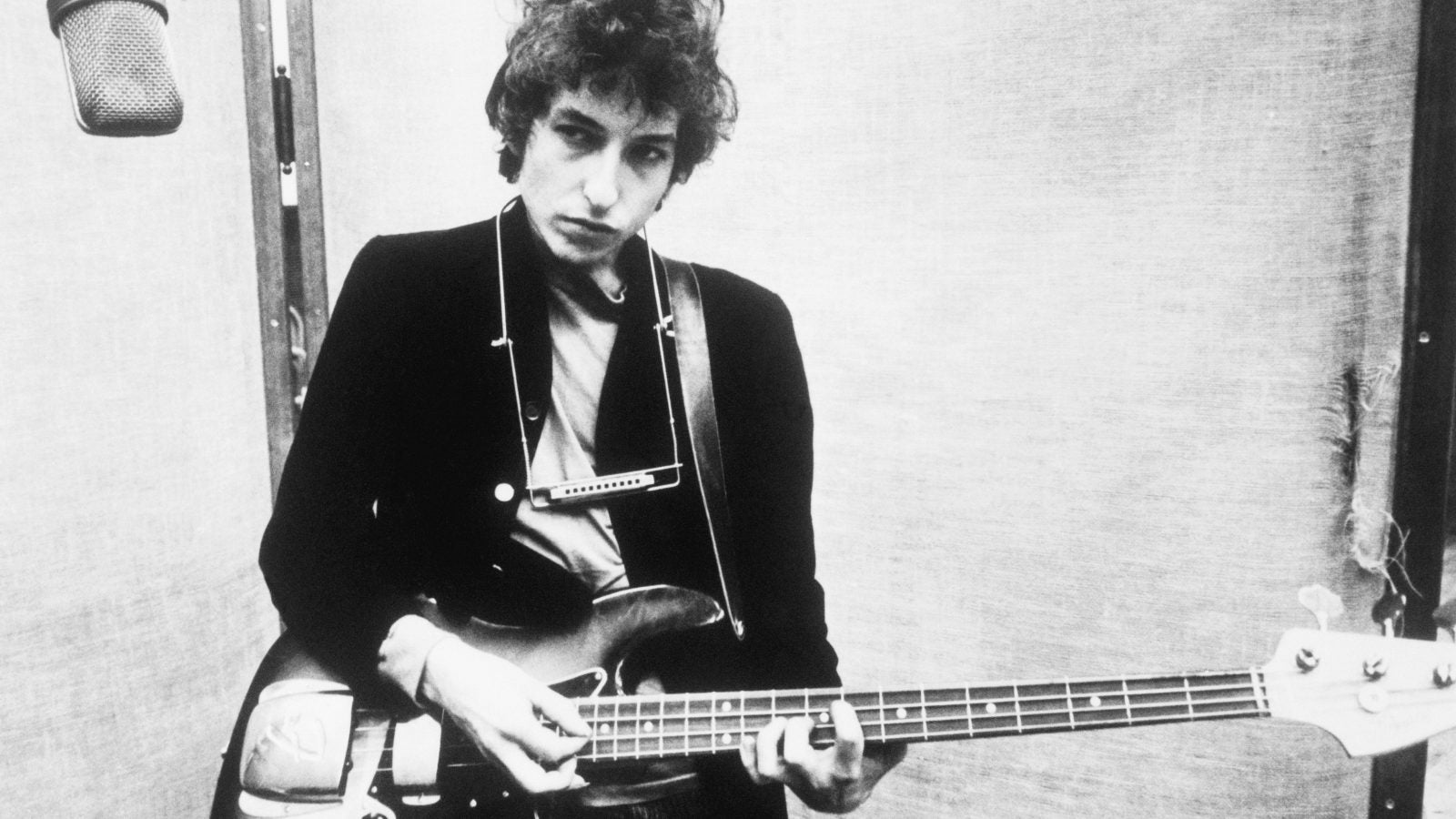

Bob Dylan’s greatest work of fiction is himself

Just don’t call Bob Dylan, the American songwriter who today became the first musician to win the Nobel Prize for Literature, the “voice of a generation.”

Just don’t call Bob Dylan, the American songwriter who today became the first musician to win the Nobel Prize for Literature, the “voice of a generation.”

Dylan himself has shied away from that particular yoke.

To be known as the voice of anything—a time, a movement—is to be fixed. And even when hitting the peaks, capturing the moment and encapsulating it in lyrics and music, Dylan has insisted on nothing so much as his right to change, then change again.

As a man who has been writing, singing, and touring for most of the last 54 years—discovered and adored anew by wave after wave of music-lovers, literary scholars, and introspective teenagers—Dylan has shown that certain voices can transcend time, generation, and genre.

Dylan’s work has evolved throughout his career, from acoustic folk to rock, and from protest songs to songs people want to protest against. He has been notoriously difficult to interview, to pin down, to categorize. He has also upset his fans by changing tack.

The filmmaker Todd Haynes, a chameleon in his own right, in 2007 released I’m Not There, a weird and brilliant non-biopic in which six actors played seven versions of Bob Dylan, none of them called Bob Dylan. The character most like Bob Dylan’s visible public persona, a singer called Jude, was played by Cate Blanchett.

In an interview with Rolling Stone, Haynes suggested that while reinvention comes with loss, it could also be necessary:

But what’s so amazing about Dylan is that each of those transitions from character to character or self to self, which come with a death – the death is built in – is also a liberation into a new self, a new identity. And whether that is due to the unique constraints of a highly coveted popular artist who needed to eke out some fresh air for himself to create new work or just constitutionally part of his psyche, it’s a healthy erraticality.

Academia and the establishment have for years been taking bites out of Dylan—prolific, profound, and maddening as he is—to feed themselves. The literature prize is a nice twist in a tale about changing direction and foxing pursuit.

And of course, in winning the most venerable of establishment awards, he’s still confounding expectations.