My balls-out fight against testicular cancer

I had been living in Berlin for nearly six months when I had a bit of a kick in the nuts.

I had been living in Berlin for nearly six months when I had a bit of a kick in the nuts.

Skyping my girlfriend in Australia, things were getting a little raunchy when I first came across “it”—“it” felt like a lumpy marble lodged inside my ball sack.

I went a little white. It was definitely a mood killer.

My girlfriend suggested it was an infection of some kind, but Dr. Google and my own suspicions said otherwise. I spent the next few hours searching “lump in my testicles,” which lead me to discover various facts and figures on my condition. Most signs pointed to testicular cancer, which is the most common cancer among young men in their 20s and early 30s. According to Cancer Research UK, in 2013 2,296 new cases were reported in the UK alone—and over half of those were in under 35 year olds. I was 35. My heart sank a little.

I had no idea how long the lump had been there, but one thing was clear—I needed to get it checked by a doctor, pronto. I went to bed fearing the worst, and work the next day was fretful. I was working for a new art gallery that was just starting up, and we had a new girl in who needed a lot of help. I didn’t have the patience or mindfulness to give her the answers and help she needed, and when she left the room, I crumbled and broached the subject with my male colleague. He immediately told me to take the rest of the day off and get checked out at hospital.

Digging out my health insurance papers, I got outside to find my car battery was dead, which spiralled me further into sweaty panic. After a quick jump from a taxi, I was on my way to one of Berlin’s extremely clean, well-equipped university hospitals. With a mix of crappy German and average English, I awkwardly explained to the nurse what the issue was and joined a handful of other people in the emergency waiting room. A short time later I found my balls being fondled by a young doctor who covered my nuts in clear gel and examined the lump with an ultrasound. He seemed more nervous than me.

My Google doctorate had furnished me with the possibility that this was probably cancer, and I’d probably lose a bollock. My doctor confirmed that I was most likely correct. A few minutes later, some more gel, an ultrasound, and more fondling, and his colleague concurred. Both of them asked if I’d had any complications when my balls dropped in childhood, but I could barely remember what I’d done last week, let alone whether one of my plums had struggled to drop when I was a kid.

I resigned myself to the fact that this was happening, and for a moment I was oddly elevated, almost nonchalant. I felt I was lucky that I’d found it reasonably early, that I was in the best sturdy German hands, and that all of this was going to be totally fine. Testicular cancer has a relatively low chance of metastasis to your lymph glands, lungs, and brain—and even to the other testicle. Although there are no real preventative measures to guard against the disease, it is extremely curable, especially if caught early. Testicular Cancer Society figures put the success rate at over 95%. I felt pretty small and afraid for a moment, but in the grand scheme of horrible things happening in the world, if all I had to endure was losing one of my balls, things really weren’t that bad.

But when the doctors left the room, I blinked back tears. Left alone, the possibility that it could have spread likewise metastasized through my brain.

My personal health aside, I’m not ashamed to say that I was also afraid I’d lose all the parts that essentially made me feel like a man. I suddenly felt as if all my masculinity was essentially reduced to a few dangly bits between my legs, leaving me questioning what it really was that made me a man.

As men, the media has taught us that we’re all supposed to stay strong and never show emotion or weakness. It’s instilled in us from a young age with chiselled action heroes and staunch, emotionless stereotypes. It’s hammered home in the playgrounds and streets every time we call each other chicken—or worse. Whereas women are often typified as emoting their feelings, men are supposed to bottle up their emotions and pretend everything’s just fine. So initially, that’s what I did. I went home feeling stunned and fell asleep exhausted.

The next morning I headed back to the hospital for more checks. It was a long day of ball-fondling, forms, signatures, and the option of freezing sperm. Thinking this was the only chance I’d ever get to be offered a cryology service, I said yes without blinking.

It was pretty surreal. I saw an older nurse who took some information from me, slapped a label on a small container, and showed me to a small room with a solid, lockable door and a decent box of tissues. Safely entombed in my chamber, I looked around at the contents of the room: a Pirelli calendar and a few soft-porn mags from the 1990s. They looked glossily back at me from beneath pastel eyeshadow and bouncy ponytails.

I reached for my phone and called my girlfriend for help.

Dropping off the sample, I watched in embarrassment as the nurse swirled it around in the light, seemingly happy with the result. A few more forms, another couple of different clinics, blood, and urine samples, and a surgery appointment locked in… and I was apparently free to go.

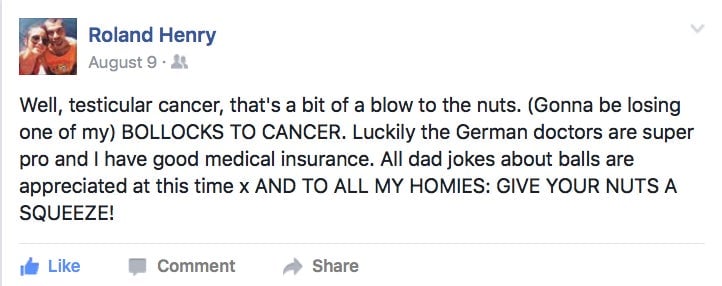

I headed home thinking of who I was supposed to tell about this sort of thing. Wanting to let as many people as possible know so I didn’t have to repeat the story a million times, I decided to drop a Facebook post about it, explaining as light-heartedly as possible that I had testicular cancer and everyone else should check their chaps too.

Sharing the news of my health felt like I’d broken some kind of sacred man-code. However, having grown up with three sisters and my mum predominantly taking care of us on her own, I guess the female influence helped show me that I could be vulnerable without compromising what it was to be a man.

The response was amazing. I was overwhelmed with people offering their support and encouragement for sharing my story so openly. Inadvertently, I’d spoken about something that touched people. I didn’t feel heroic, or big, or even particularly brave, but it seemed I’d opened up something inside my friends that they could all relate to—the vulnerability and humanity of us all.

Two days later and I was in surgery at 6:30am. Donning a medical gown, I was put into a small holding room with a couple of other uncomfortable inmates heading in for human butchery. It wasn’t really until I was being wheeled into the operating theater that my veneer of sensible, rational thought disappeared. My mantra of “Everything Will Be Fine” gave way to “Oh My Fucking God They’re Going To Castrate Me.”

My benign serenity faltered. I began to panic. What happened if the other one had cancer as well? What happened if they took both of them and I could never orgasm again? What happened if my dick got cancer and they took that off too?

Trying not to breathe too heavily, I nodded as bravely as I could at the nurse clamping on my oxygen mask. Counting back from 10, I felt the blackness of the anaesthetic crawl up my arm.

I woke up feeling like I’d been thrown down a flight of stairs and then kicked in the goolies. An old guy was coughing to my left. A younger bloke was lying over to my right, staring out of the window. I coughed and immediately winced.

A few close friends made the pilgrimage to see me, and I did my best to entertain them, but I got tired pretty quickly. After a couple of days I was allowed out, and I spent most of the following weeks lying down. My girlfriend was amazingly supportive during the whole process, and despite my fears that she’d be scared off by the ordeal, she was a total rock throughout. A CT scan and outpatient appointment confirmed I was cancer free just weeks later, and I was well on the road to recovery.

I felt super fortunate. The doctor confirmed I’d been “unluckily lucky” in many ways—the cancer was one of the least aggressive forms, and I’d found it early. There was no spread, and I was completely covered under my work’s health insurance.

A month and a half later and I’m as healthy as I ever was. I’m supposed to go for a short, mild chemo session to reduce my chances of other cancer from 15-20% down to 2-3%, and I’ll need to go for yearly check-ups to stay on top of things. But, for now, it already seems like a distant memory.

The response from friends and family and the huge amount of support I’ve received across the board has been amazing, but the best thing about it was the messages from friends who came out with their own stories of cancer battles or approached me with private concerns over their own bodies. Hopefully me speaking out about my issues has enabled a few others to realize that it’s really not that scary to man-up and get their junk seen by a specialist or to cop a feel yourself.

It might still be viewed as “weak” by the old guard to discuss your fears or concerns, but hey—it’s 2016. We men should be able to talk about stuff like this openly without stigma or judgment. Women speak openly about breast and ovarian cancer in both private and public forums, and that helps raise awareness and provide vital early treatment. The fact I was so open about my own ordeal probably saved my life—and hopefully it will save a few others’, too.