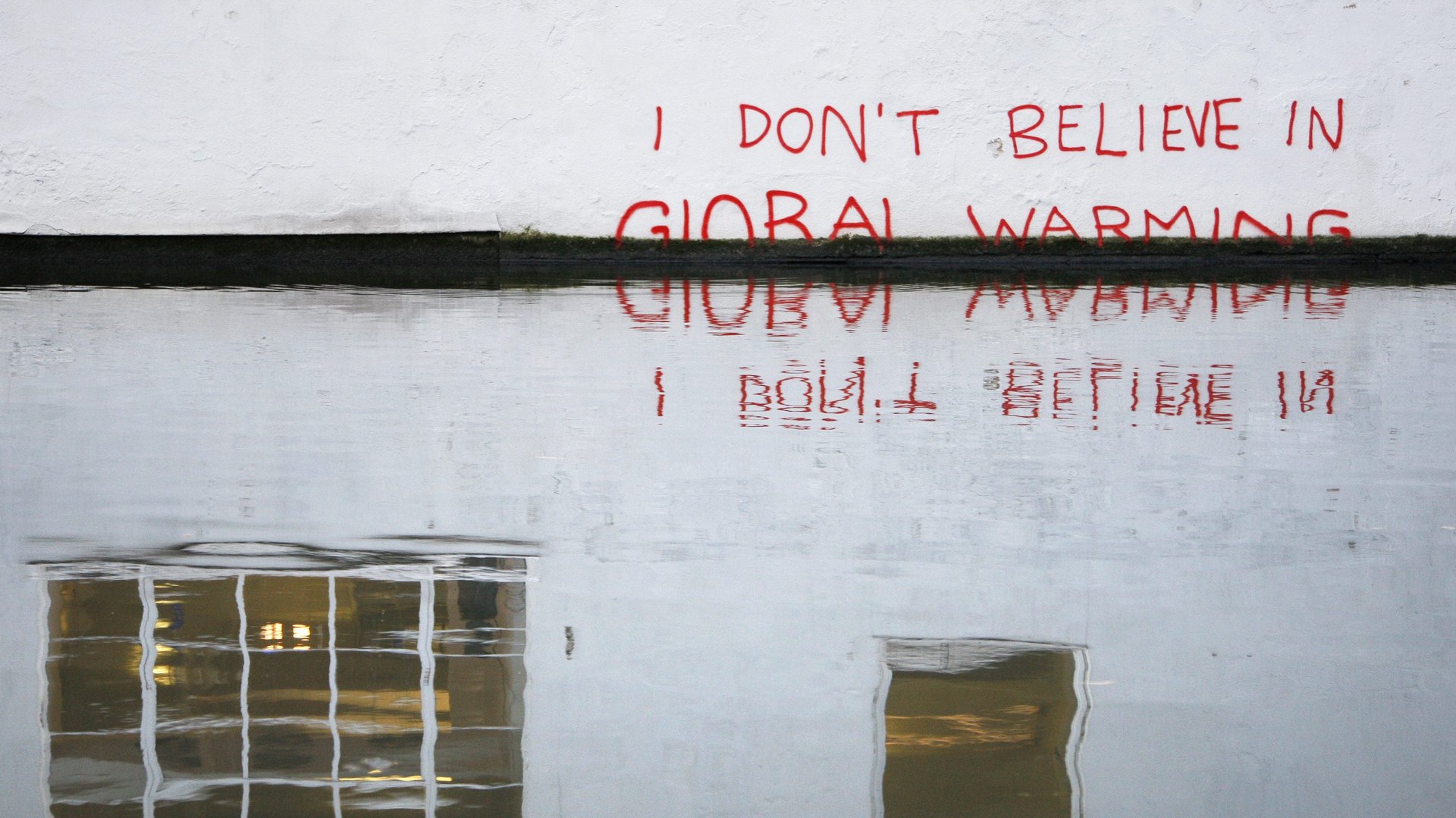

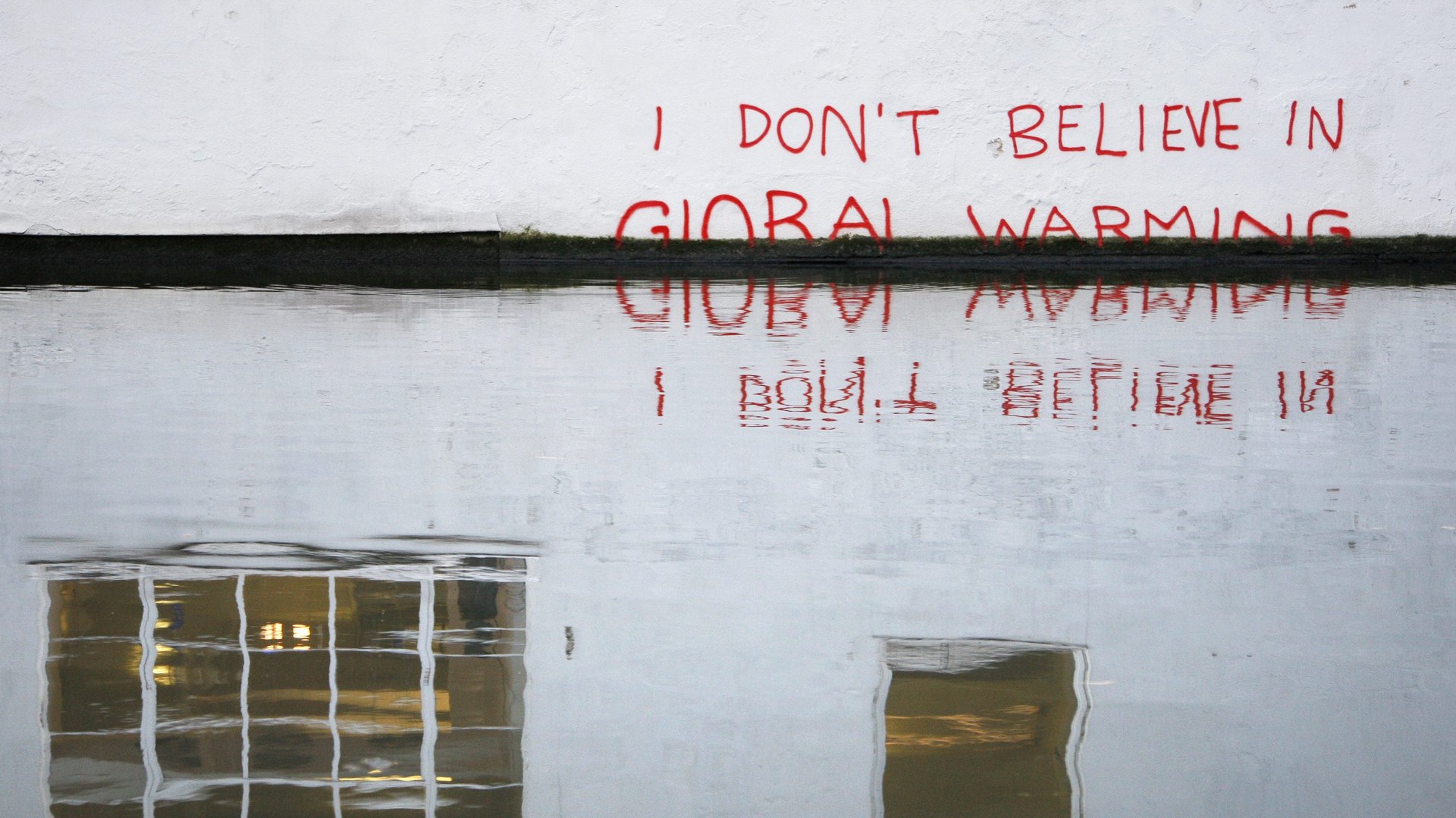

You need to get inside the mind of a climate change denier if you want to change it

It has never been more important to figure out how to have constructive conversations with climate change deniers.

It has never been more important to figure out how to have constructive conversations with climate change deniers.

Whether the current global climate change was caused by the actions of humans should no longer be a topic of debate. In 2013, a survey undertaken of over 4,000 academic papers published over the previous two decades found that 97% of the scientific literature agreed: humans are causing climate change.

And yet, the US, which was instrumental in bringing together world leaders to sign the Paris Agreement, has elected to the presidency Donald Trump, who has called climate change a Chinese hoax designed to hurt American manufacturing. Trump has vowed to remove the US from the Paris Agreement (not an idle threat) and has picked Myron Ebell, a well-known climate denier, to lead his Environmental Protection Agency transition team.

Trump and Ebell are not outliers. According to a study by sociologists Aaron M. McCright and Riley Dunlap, based on an analysis of Gallup surveys of public opinion between 2000 and 2010, 32% of adults in America deny that there is a scientific consensus on climate change. There’s a clear political divide on the issue in the US: According to a 2016 survey by Pew Research, only 15% of conservative Republican Americans agreed with the statement “the Earth is warming mostly due to human activity,”compared with 79% of liberal Democrats.

The fight over climate change policy is often characterized as economy-versus-environment. But Brock University psychology professor Gordon Hodson and PhD student Mark Hoffarth think there’s a better explanation: In the US, environment is typically seen as a liberal concern, with climate change mitigation and green energy policy originating with the Democratic party and its voters. That leads members of the right to push back for political reasons, regardless of how they feel about the actual issues, Hodson says. “Those on the right who are denying climate change think that left-wing environmentalists have an agenda and that they’re hijacking this climate change movement as a way to further their agenda.”

Overcoming the political gap that characterizes climate change discussion in the US will not be easy. The first step is to better understand what drives someone to believe that climate change, despite the overwhelming scientific evidence to the contrary, is not real.

The psychology of a climate change denier

McCright and Dunlap’s work parses the numbers even further: while about 3 in 10 American adults don’t believe that human activity causes global warming, the number doubles for conservative white men—6 in 10. That gender modifier is important: McCright told the New York Times he found that 14.9% of conservative white females believed the scientifically predicted effects of global warming will never happen, as compared to 29.6% of conservative white men.

McCright and Dunlap offered two different psychological explanations for the phenomenon. The first is called the “system justification” theory, which argues that people are subconsciously impelled to defend and reaffirm the status quo. As conservative white men have benefited by the current socio-economic structure, they are most therefore more likely than women or men of other backgrounds to be predisposed to preserving it.

The second explanation is called the “identity protective cognition” theory, which, according to a study led by Dan M. Kahan at Yale Law School, is when individuals selectively accept or dismiss risks in order to preserve a socio-economic structure beneficial to them. In other words, white men are not inclined to accept as real certain dangers—such as the hazardous impacts of continued carbon emissions—when they challenge their preferred way of life—in this case, one built on a fossil fuel economy.

Kirtsi Jylha, a lecturer at Sweden’s Upsala University, recently published a doctoral thesis that used data from surveys done in Sweden and Brazil to identify correlations between certain personality types and climate change denial. She also also found that climate change deniers are more likely to be men.

“Men tend to be socialized not to think about nature or taking care of people to the same degree as women are,” she says. “They also tend to score lower in empathy.” Likewise, in her study climate change deniers tended to exhibit a low capacity for empathy, borne out by positive responses to questions such as, “Other people’s misfortunes do not usually disturb me.”

Climate change is caused to a high degree by a wealthy lifestyle—and its impact is felt more by less developed countries and individuals who don’t have the resources to adapt. “It is possible that people who do not believe in climate change are not thinking about it because it doesn’t bother them that this rich lifestyle is affecting people who have fewer resources, both globally and also within societies,” says Jylha.

The typical denier is also predisposed to avoid negative emotions. In Jylha’s study, those who answered yes to questions such as “I avoid thinking about things that cause anxiety” were found to be more likely to deny climate change. Climate change denial might for them be a kind of buffer against a psychological existential threat, says Jylha.

In States of Denial, sociologist Stanley Cohen argued that denial can be a form of coping with the negative emotions that emerge when we think about catastrophic events. Denial can then be seen as an “unconscious defence mechanism for coping with guilt, anxiety, or other disturbing emotions aroused by guilt,” he wrote. “The psyche blocks off information that is literally unthinkable or unbearable.”

There’s one particular personality trait that underpins most of these other correlations: social dominance orientation.

In psychology, social dominance orientation is a measure of an individual’s acceptance of hierarchical power structures and inequality between social groups. Those who score high in surveys measuring social dominance orientation tend to see the world as an ongoing competition between social groups, and think it’s normal that some groups are at the bottom and others are at the top.

Jylha says that if you control for social dominance orientation, some of the other correlations she found reduce or vanish. For example, social dominance orientation mediated most of the effects of gender and personality variables on denial in her study.

Research has also shown that people who accept dominance over certain social groups are also highly likely to accept human dominance over animals. A study led by Kristof Dhont, a lecturer in psychology at the University of Kent, found that social dominance orientation can predict whether someone has a speciesist attitudes towards animals—in other words, that he or she believes human beings by virtue of their species have greater moral rights than non-human animals.

Another study, led by Taciano Milfont from the University of Wellington, shows that social dominance orientation predicts a person’s support for environmental exploitation, to the extent that harming the environment widens the gap between social groups. According to the study, those who exhibited social dominance orientation supported a new mining operation only when it was expected to generate further profits to high-status groups—and not when profits were equally divided between all.

How to talk to a climate change denier

The takeaway from all this, Jylha says, is that appealing to a sense of empathy towards victims of climate change—whether that’s other people, animals, or plants—is not an effective tactic with deniers. Instead, research shows, they are more likely to respond to arguments of how society at large can benefit from climate change mitigation efforts.

A comprehensive study published in 2015 in Nature surveyed 6,000 people across 24 countries and found that emphasizing the shared benefits of climate change was an effective way of motivating people to take action—even if they initially identified as deniers. For example, people were more likely to take steps to mitigate climate change if they believe that it will produce economic and scientific development. Most importantly, these results were true across political ideology, age, and gender.

In order to appeal to those who deny climate change, discussions should focus on convincing people to take on behaviors that would help protect the environment—without trying to convince them to become environmentalists. The renewable energy economy is a great example. Arguing that innovation in alternate energy sources would lead to the creation of jobs does not necessarily require convincing someone of the harmful impact of climate change.

If all else fails, you can resort to John Oliver and Bill Nye.