The rare country where voters are less worried about immigration than about emigration

In recent years, appealing to nationalist, anti-immigrant sentiment has been a reliable vote winner in many parts of the world. From economic insecurity to the fear of terrorism, the factors fueling a populist rejection of immigration vary in each place.

In recent years, appealing to nationalist, anti-immigrant sentiment has been a reliable vote winner in many parts of the world. From economic insecurity to the fear of terrorism, the factors fueling a populist rejection of immigration vary in each place.

And then there is Lithuania.

In a recent survey, people in the small Baltic country showed little appetite for the “authoritarian populist” views held by many elsewhere (around 20% in Germany, 50% in the UK, 60% in France). A major upset in the second round of Lithuania’s parliamentary election this weekend highlighted the country’s unique position.

A small, centrist party founded by farmers unexpectedly won the most seats in the vote—54 out of 141 in parliament. The Lithuanian Peasant and Greens Union, which had only one seat before the election, achieved this feat on a platform of stopping emigration—that is, keeping people in.

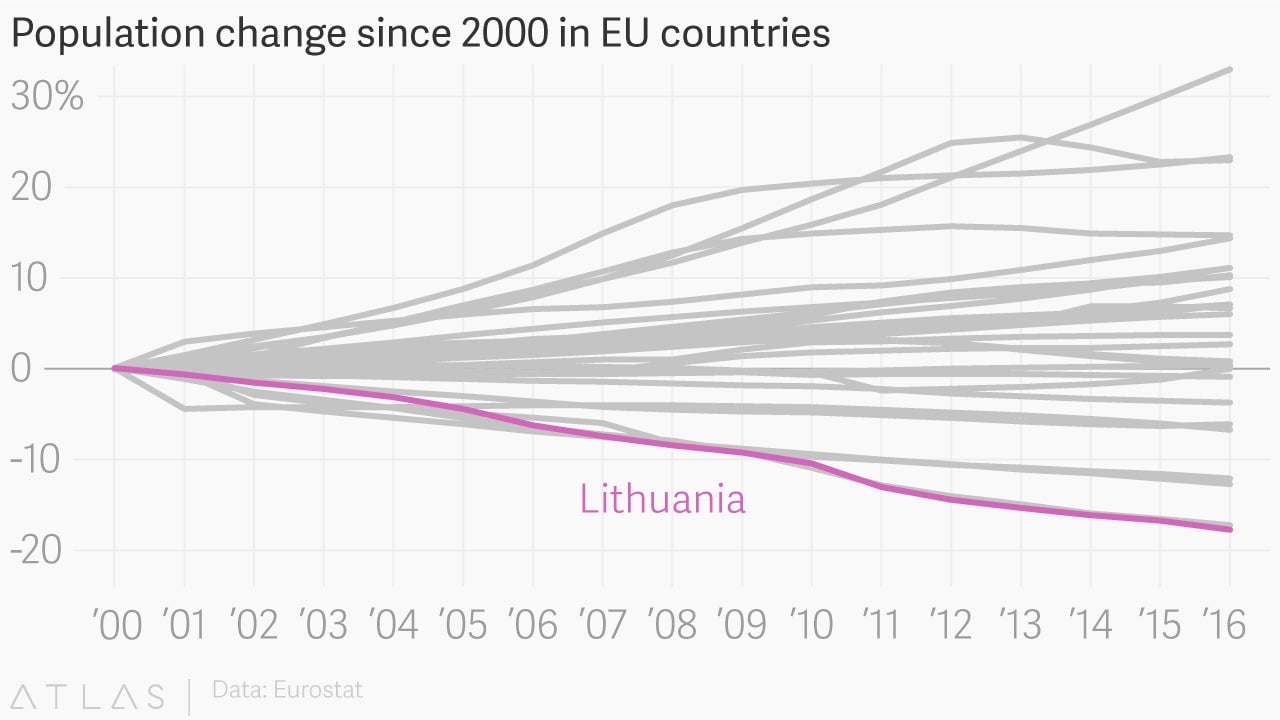

It’s easy to see why this is an issue: Since 2000, no EU member state has shrunk as fast as Lithuania.

Low wages at home have pushed many Lithuanians to try their luck abroad, made easier by the right to travel freely in Europe since the country joined the EU in 2004. Lithuania’s population has fallen by 500,000 since then. In a country with just under 3 million residents at last count, half a million is a lot. Around 160,000 of those Lithuanians now live in the UK, a particularly popular destination for migrants from all over the EU, especially those from the east.

Lithuania’s ugly demographic decline risks becoming self-fulfilling, as the costs of supporting a shrinking, aging population will make life even less attractive for young people. Ramunas Karbauskis, leader of the Peasant and Greens Union, said he is open to forming a coalition with any other party “if we agree on the major challenge: how to stop citizens fleeing Lithuania.”

On its current course, Lithuania will shrink by another 40% between now and 2080, according to the EU’s latest population projections. That would cut its peak population in the early 1990s almost exactly in half.