Researchers developed a facial photo-matching game that reverses racial bias in children

In a recent study from Yale University, preschool teachers were found to spend more time watching African-American children, and especially boys, for signs of misbehavior, than they did children of other races.

In a recent study from Yale University, preschool teachers were found to spend more time watching African-American children, and especially boys, for signs of misbehavior, than they did children of other races.

Sadly, this didn’t surprise anyone who knew it to be true from experience.

What fewer of us realize, however, is that people of almost all races begin to show an implicit bias for their own race well before they enter preschool. Fortunately, it’s possible that bias can be unlearned by teaching children to recognize the faces of people of unfamiliar races as distinct.

Landmark research from 2005 found infants as young as 3 months old have a preference for own-race faces. More recently, a global team of psychologists from universities in China, the United States, Canada, and Cameroon, learned that children can show a strong racial bias against other races by age 3.

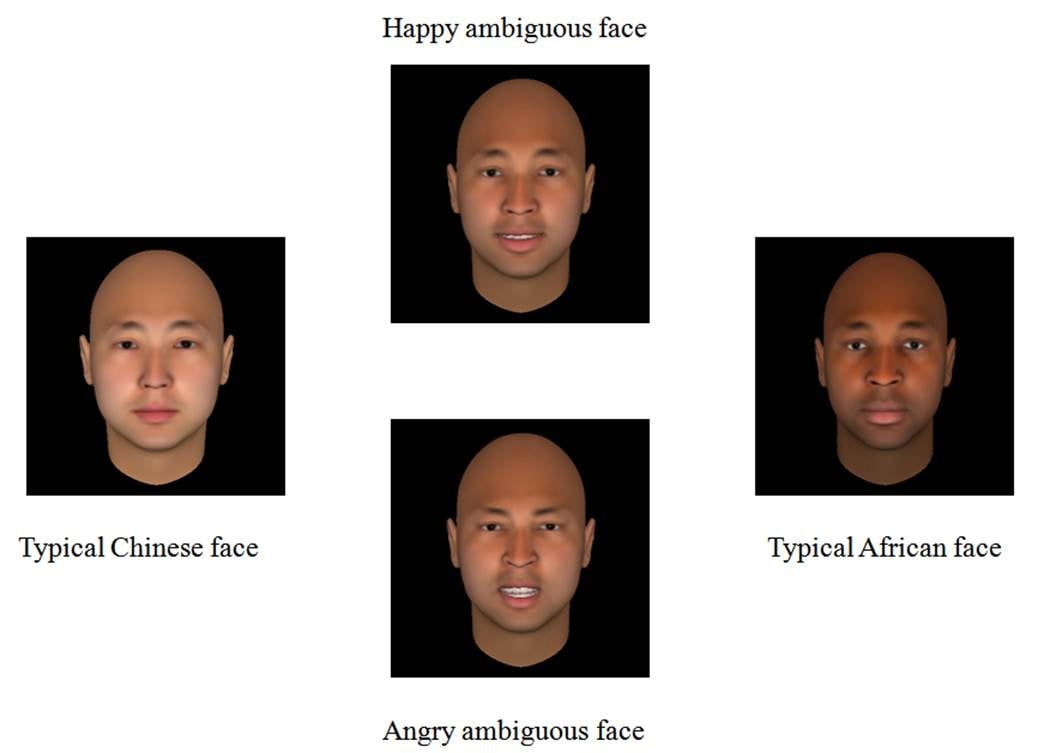

The scientists tested for implicit racial bias in both adults and preschool-age children in China and Cameroon, which are racially homogenous societies. To do this, they used software to create faces that were exactly 50% of one race and 50% of another. In China, the subjects were shown faces that either morphed Chinese and African features, or Chinese and white features. In Cameroon, subjects were shown faces that were African-Chinese and African-white. In both experiments, some of the faces were then made to look slightly angry and others a tad happy.

When asked to identify which race a face represented, the children in China described those with angry expressions as African or white (depending on the test), and the happier ones as Chinese. In Cameroon, the children showed the same implicit bias against the races of outgroups, both whites and Chinese.“For years we used to think parents socialized kids to have implicit bias, but these kids had no experience with other races, and neither did their parents,” says co-author of the research, Kang Lee, a University of Toronto professor of applied psychology and human development.

These findings, which were published in Child Development, led the scientists to believe that the children were likely extending a negative perception about an unknown race to all people of that category. This is a symptom of the so-called “other-race effect,” which makes it challenging for a person to make distinctions between the individual faces of another race. (It’s at play when you hear someone make the cringe-inducing comment that people of one group “all look alike to me,” but it doesn’t always suggest underlying racism.)

Because learning to individuate faces has been shown to reduce race-based implicit bias in adults, the researchers decided to test the method with children.

In a follow-up study, published in Developmental Science last year, the researchers asked 69 kids from a southeastern city in China, aged three to five, to memorize the assigned numbers (proxies for names) of five African men whose faces were displayed in photographs. The men in the photographs, whose facial expressions were neutral, were all between 20 and 35 years old, and had similar hairstyles. The children needed to learn their names with 100% accuracy, and would repeat the task until they did. “This took about 20 minutes,” says Lee. Then, the same children were tested for implicit racial bias again, and were found to have none. “To be honest, we were surprised it worked so well,” Lee confesses.

A control group of 61 children had matched names with Chinese faces, and their implicit racial biases against African-Chinese faces showed no change. They still believed the slightly angry faces belonged to Africans.

Encouraged by the name-matching task’s success, the scientists still needed to know whether the effects would be lasting. In studies that are due for publication shortly, they found that one week after undergoing the training, the students’ implicit biases had returned. However, when students in China were trained to match names and faces with 100% accuracy twice, one week apart, their implicit biases remained low for 70 days.

In other words, short bursts of anti-racial bias exercises may be the best option for an intervention program, according to the researchers. (They have not tested the name-matching training in Cameroon, and the study in China didn’t include training with white-Chinese faces.)

“We have known for years if you have direct contact with other races, your implicit racial bias is much lower,” says Lee, “but in some places, even in the US and Canada, if you go to rural areas, there are very few other races, and there’s no way to naturally make interactions happen. Our method opens up a way of conveniently reducing implicit bias through training.”

Books and movies featuring diverse characters can be helpful, too, he notes, but only if children are given the opportunity to learn other people’s names. “If you learn to treat each individual as an individual, you avoid this kind of categorization by race,” he explains.

“It takes some time to convince people of this, because it’s so simple. People say, ‘It’s too easy,’” he adds, “But it actually works.”