A short history of 150 years of paper currency in India

Knowing that the current Rs500 and Rs1,000-denominated notes are now a relic of the past makes you look at them differently. In one night, what was once legal tender became nothing more worthy than Monopoly money.

Knowing that the current Rs500 and Rs1,000-denominated notes are now a relic of the past makes you look at them differently. In one night, what was once legal tender became nothing more worthy than Monopoly money.

And yet, the Narendra Modi government’s sudden move on Nov. 08, which preceded the introduction of new notes, was only the latest milestone in the long story of the Indian rupee’s evolution in paper form.

For many of us, the old versions featuring Mahatma Gandhi on one side were all that we ever knew. Though the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) introduced an updated version of the notes in 2005 (eventually all the notes, and not just the high-denomination ones), with some new security features, the overall look and design remained similar to the original style, introduced in 1996. These notes were, however, preceded by decades of changes in symbols, colours, sizes, denominations and more—a rich history that harks back to the colonial era.

The birth of a paper currency

Until the 18th century, silver and gold coins were commonly used in India. But as private European trading companies established their own banks in the region, such as the Bank of Hindostan in Calcutta, they began issuing the very first versions of Indian paper notes, which were initially just text-based.

As British companies began increasing their hold over what were then Bengal, Bombay, and Madras, they established presidency banks, beginning with the Bank of Bengal. This further popularised the use of paper notes. The Bank of Bengal went on to release notes that featured a small image of a female figure meant to represent the idea of “commerce,” as well as the bank’s name and the denomination in three scripts: Urdu, Bengali, and Nagri.

However, it was only after the Paper Currency Act of 1861 that the British colonial government really got involved in producing money, establishing the paper currency as we know it today. Money was now to be issued by the state alone, not banks. The new law was the brainchild of James Wilson, the finance member of the India Council that advised the British in India. Wilson effectively was a sort of finance minister in the colonial government. (Incidentally, he also founded the Economist newspaper in 1843 and was the founding director of the Standard Chartered Bank.)

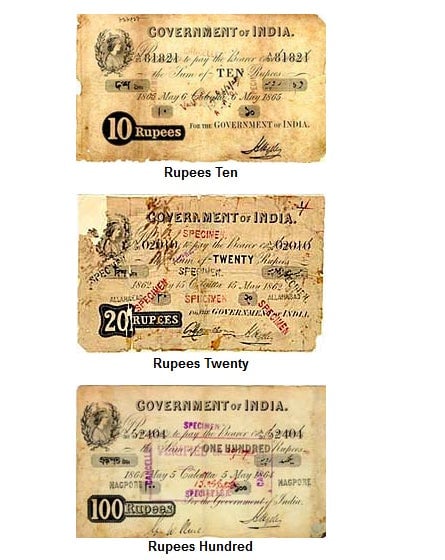

The “Victoria Portrait series” notes were the very first paper notes officially introduced by the government, available in denominations of Rs10, Rs20, Rs50, Rs100, and Rs1,000. The notes had details provided in two languages, as well as a small portrait of the queen on the top left.

At the time, as Manu Goswami explains in her book Producing India, the vast mass of the region was divided into “currency circles,” each with notes that could only be used within a specific area. These circles were centered on cities then known as Calcutta, Bombay, Madras and Rangoon, as well as Kanpur, Lahore, and Karachi.

Interestingly, in instances when money had to be securely transferred across distances, the paper notes were sometimes cut in half, with one half being sent by post first and the second sent only after the first reached the destination, according to the RBI’s Monetary Museum.

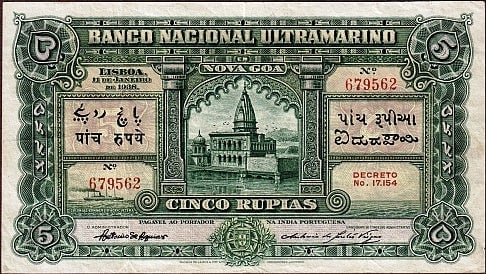

Other colonial governments also printed notes for use in their territories in India. For instance, France’s Banque de l’Indochine issued its own “roupie” notes in the late 1890s and these stayed in circulation right up to 1954, when they were replaced with Indian government notes. The Portuguese issued “rupia” notes starting in 1883 and they were used until 1961.

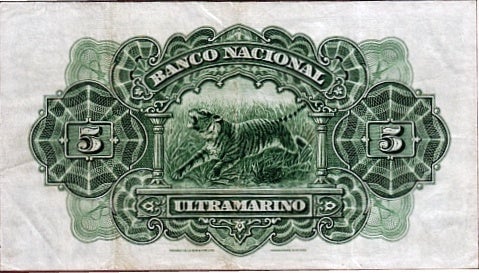

As British influence grew over the years, the denominations and styles of their currency notes in India evolved; they began to feature more languages and details, as well as the portraits of kings, starting with George V in 1923.

All these notes were printed by the Bank of England until India’s first currency printing press was established in Nasik in 1928. Four years later, this press was producing all of India’s notes. In 1935, the responsibility of managing India’s money was handed over to the newly-established RBI.

Money for modern India

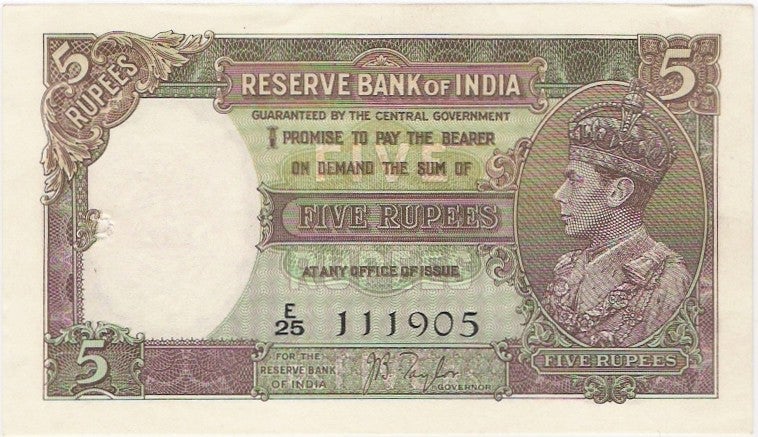

It took RBI several years to launch its own notes and the first versions looked similar to the earlier editions of the colonial government. RBI’s first note was issued in 1938 and featured a portrait of King George VI:

After Independence in 1947, India’s currency needed a new look, with imagery and symbols to represent its new identity. The first post-Independence note came out in 1949: The Re1 had the image of the Lion Capital of Ashoka at Sarnath, which would also become the official emblem of India, printed on the top right.

Over the next few years, RBI released notes of different denominations featuring images of monuments such as Mumbai’s Gateway of India and the Brihadeeswara temple in Tamil Nadu’s Thanjavur town. In the 1960s, notes began to be printed in different colours to help people who couldn’t read.

The Ashoka pillar remained one of the main images on most notes until the 1980s when the next redesign occurred. This time the motifs oriented towards Indian art forms and symbols of scientific and economic progress, a nod to the country’s development.

But perhaps the most important transformation over the years was technological. In 1944, fearing the infiltration of Japanese forgeries in the latter years of the Second World War, RBI introduced a security thread for the first time on its notes, as well as an updated watermark. Decades later, in 1996 and in 2005, it released versions of a new “Mahatma Gandhi series” of notes. These came with an updated range of security features, including a latent image that could only be seen when the note was held up to light in a certain way. Special inks were used for the various texts and the notes carried details that could help the visually-impaired.

The last design change in recent memory was the inclusion of the new rupee currency symbol, first adopted in 2010. Notes bearing this symbol, a combination of the Devanagri ‘Ra’ and Roman ‘R’, were printed for the first time in 2011.

The money of tomorrow

Today, these notes are still an essential part of daily life, even as credit cards and online payment services are becoming increasingly popular in urban India. But the demonetsation of the Rs500 and Rs1,000 notes, the first such step in nearly 40 years, has paved the way for further evolution of India’s paper currency.

The two new notes feature Devanagari numerals, along with the usual international standard ones, a surprise addition given the long-running debate over the status of India’s many languages.

The Rs500 note is now slightly smaller and stone grey in colour but still features the Mahatma. On the reverse, RBI has added the spectacles logo of Swacch Bharat—prime minster Narendra Modi’s pet “clean India”campaign—and an image of Delhi’s Red Fort. Meanwhile, the Rs2,000 note is magenta in colour and represents India’s Mars orbiter mission, a new symbol to mark the distance that the country has travelled over its long history.