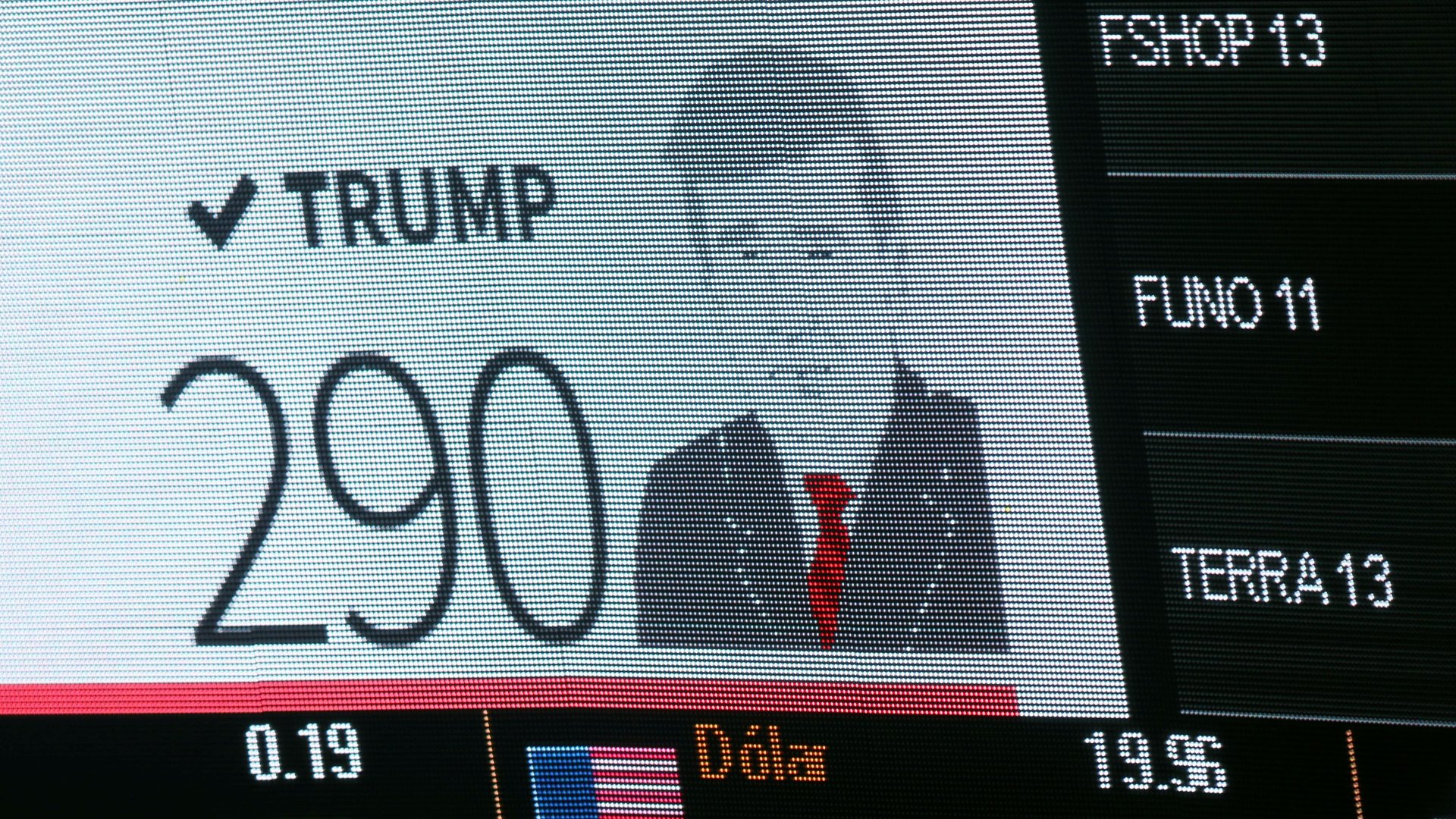

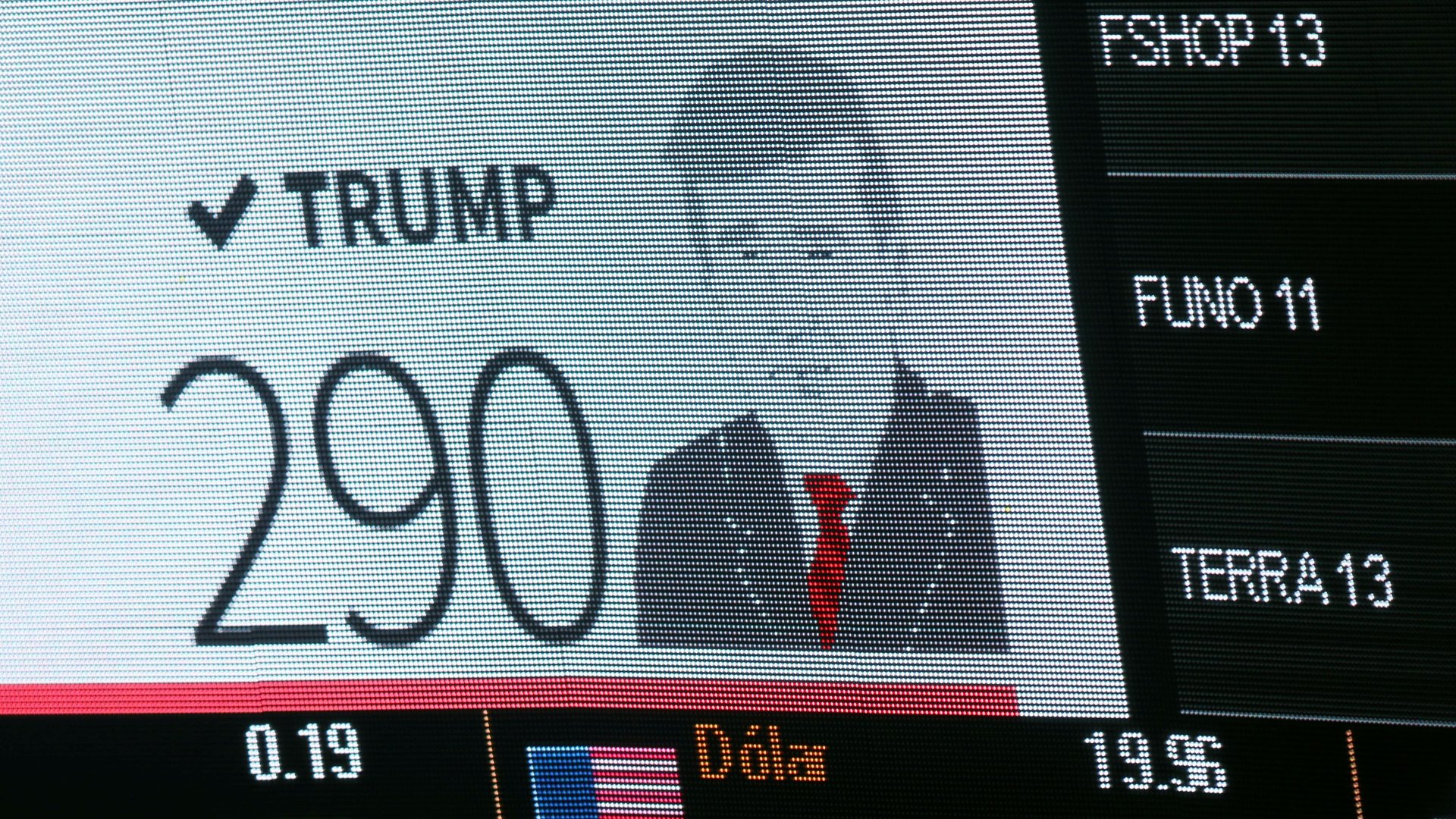

The swing of financial markets after Donald Trump’s victory is a strong indicator of what’s to come

Global financial markets plunged—and then recovered—as Donald Trump won the US presidential election.

Global financial markets plunged—and then recovered—as Donald Trump won the US presidential election.

The Standard & Poor’s 500 and the Dow Jones Industrial Average were up about half a percent around noon as investors more calmly absorbed the election results following a night of panic. Futures on the S&P 500, for example, had tumbled as much as 5 percent, and the Mexican peso—which has been a key indicator of investor sentiment during this race—plummeted as much as 12 percent, to a record low.

While investors around the world continue to digest the results, a central issue for them is how the outcome will affect their assets. But do the markets’ reactions tell us anything about the future, as well?

As it turns out, whether markets—specifically stocks—continue to fall or begin to rise over the next few days can be a useful predictor for how they will perform in the months and even years to come. In the case of the 2016 presidential election, investors will decide whether they think Trump will be good or bad for the economy—and more importantly their investments—as the 45th president.

The rest of us, investor or not, would be well-advised to pay attention.

Performance in the near term

In general, as you might expect, markets tend to rally if investors think the election winner will be good for their investments, and drop if they deem otherwise.

Essentially, they’re all just making bets on the future—some short term, some longer term. In particular, they may turn bullish and buy more US stocks, for example, if they think the next president will create a more favorable business climate for companies, perhaps by lowering tax rates, investing in the economy (leading to stronger growth), reducing regulation, or reducing uncertainty.

Research I published in 2014 offers evidence that the stock market’s early assessment tends to be a good predictor of how it will perform in the near future. In other words, investors cast their own votes—with their hard-earned dollars—on the outcome of the election: If more investors think that America’s choice for president will be good for the economy rather than bad, stock prices rise, and vice versa.

In my study, I examined market returns for the Dow Jones Industrial Average (DJIA)—which includes 30 of the best-known U.S. stocks such as Microsoft and Boeing—covering 29 presidential elections from 1896 to 2011. I found two key pieces of evidence that may drive investors’ stock portfolio performance both in the short term and the long term.

First, how the market reacts the day after the election appears to be an indicator of how it will perform for the remainder of the election year. If this pattern persists, then investors can expect stock returns from Nov. 10 through Dec. 31 to continue in the same direction as the returns on Nov. 9. This is generally known as the momentum effect—made popular in academic literature by finance professors Narasimhan Jegadeesh and Sheridan Titman.

In those 29 presidential elections I examined, when the market “approved” of the outcome by rallying the day after the election, stocks returned an average of about 3 percent over the rest of the year. When stocks initially dropped, the market lost an average of about 2 percent during the period.

Course correction

My second key finding was that markets tend to change their mind in a new president’s second year in office. That is, in cases where stocks rallied for the first three days after an election, the market seems to consider the initial move an “overreaction,” and vice versa.

Specifically, the DJIA lost an average of about 2.5 percent in a president’s second year if he got a victory boost during those three days. When the president-elect was initially punished by investors, stocks returned about 12.5 percent in his second year.

The reason for this anomaly seems straightforward. Media attention leading up to the election induces extreme beliefs in voters, including investors, which are reflected in trading decisions as soon as the results are known. So if the market reacts negatively to the election’s outcome and the president turns out to be not as bad as expected, then the market recovers. The opposite behavior occurs when the market reacts positively to the election’s outcome and apparently, this behavior happens frequently.

The presidential election cycle

More broadly, these findings seem to fit into a well-known phenomenon called the presidential election cycle, referring to the four years following a new president taking the oath of office.

Going back to at least the 1960s, the second half of a president’s term—especially the third year—has almost always outperformed the first half. For the last 14 election cycles, returns in the third year of a term have averaged about 16 percent, double the average during every other year.

That means for this year’s election, 2019 should be a good one for investors regardless of how markets react in the coming few days.

Some have argued the reason is that going into a presidential election year, the president is motivated to keep his party in power. Hence, he has an incentive to implement fiscal policies designed to give the economy a boost, which is usually good news for a company’s bottom line, resulting in positive stock returns.

Evidence supporting this theory, however, has been elusive. A study I published in 2013 suggested that tax policy may be behind the second-half bump because most tax legislation is passed in a president’s first two years in office, so the economic impact is felt in later years.

What does it mean?

Research has shown that Democratic presidents have historically been better for stocks than Republican presidents, but at the cost of higher inflation. So how can investors expect their portfolios to perform now that the 2016 election is over?

If history is any guide, the probabilities indicate that the market returns for the remainder of 2016 should continue in the same direction as the returns for the day following the election. The returns for the year 2018 should be in the opposite direction of the cumulative returns for the three days following the election. Finally, 2019 will likely be a positive year regardless.

Given the unusual characteristics of this election, it is hard to speculate whether or not these patterns will continue. This is the first time in history that the country may have a true outsider without military or government experience as president. So only time will tell whether these patterns will persist.

Regardless, Americans have cast their votes for president, and now investors will continue to cast their own on whether they think he will able to improve the economy. And that may provide valuable clues for investors’ portfolio performance for years to come.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.