Sub-Saharan Africa is winning the world easy money sweepstakes

We’re hardly the first to point out that weird things have been happening in the market since late 2008, when the Federal Reserve started buying mortgage-backed securities as part of a new-fangled venture called “quantitative easing.” That, in addition to similar asset-purchase programs in the UK and low interest rates around the world has left investors in a desperate “search for yield.”

We’re hardly the first to point out that weird things have been happening in the market since late 2008, when the Federal Reserve started buying mortgage-backed securities as part of a new-fangled venture called “quantitative easing.” That, in addition to similar asset-purchase programs in the UK and low interest rates around the world has left investors in a desperate “search for yield.”

It’s also apparently led them to Africa. Today, the IMF warned sub-Saharan countries to think twice about issuing debt just because it’s cheap and readily available. In its policy outlook for the region (pdf), it warned against “possible excessive fiscal expansion and public debt management problems that may impair macroeconomic stability.”

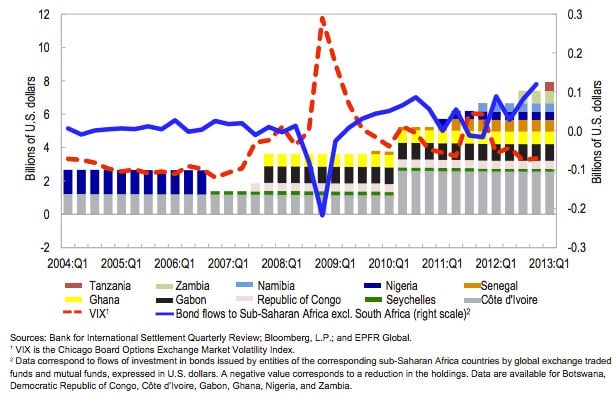

As it happens, sub-Saharan countries are issuing record amounts of debt—and foreign investors are pouring into it. (In case you can’t read the legend: the bars are the amounts of debt, color-coded by country; the red dotted line is the VIX measure of volatility, a.k.a. the “fear index”; and the blue line is bond flows to sub-Saharan Africa, excluding South Africa.)

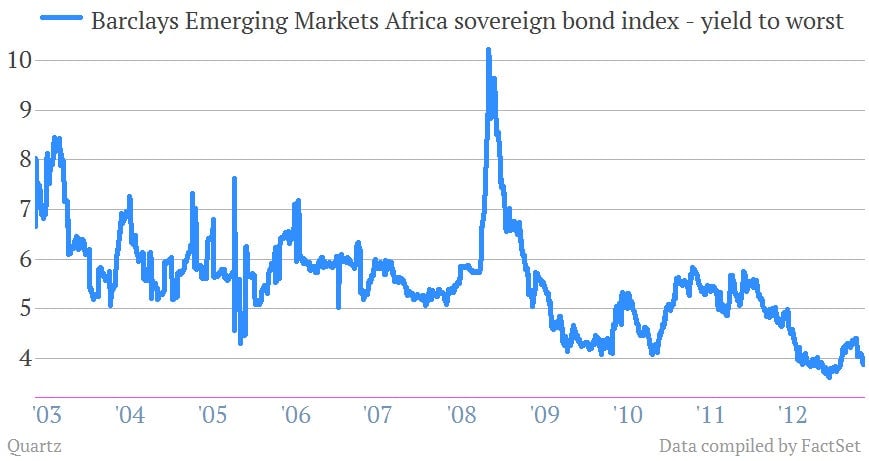

And the yield on those bonds has been astoundingly cheap. Since the beginning of 2012, the Barclays Emerging Markets Africa sovereign bond index—a compilation of government bonds from across the continent—has been yielding about 4%. (On May 9, it yielded 3.93%). In September 2012, Zambia issued $750 million in 10-year sovereign bonds yielding 5.625%—less than what 10-year Spanish government bonds were yielding at the time. Don’t forget; the World Bank last offered Zambia debt relief in 2006.

Investors are even putting money in sub-Saharan stock markets. “Although stock markets are of limited importance in the region, other than in South Africa, the search for yield among international investors meant that even modest-sized markets in countries with solid growth prospects attracted new inflows that boosted share price indices, most notably in Kenya, Nigeria, and Uganda,” the IMF said. Stock markets in Ghana and Uganda are up 80% since the beginning of 2012.

Africa may be growing, but the flood of cheap money isn’t going to last forever—and that’s why the IMF is concerned. “Given limited administrative capacity, weak fiscal institutions, low efficiency of public investment expenditure, and governance issues prevailing in some of the sub-Saharan African countries, there is a risk that increased public spending or investment projects financed by bond issuance may be poorly selected or executed and therefore would not render value for money,” the fund said in today’s report.

Since the whole point of quantitative easing is to juice the economy by propelling investors out of safe assets, it’s no surprise that some would move into riskier products—including by taking their money abroad. And central bankers can’t stop them from doing so. But “unintended consequences,” anyone?