Populists around the world are gaining ground, and it’s not looking good for the liberals

In the long-running battle at the ballot box between liberalism and populism, the world map for the populists hasn’t looked this good for some time. They have taken a decisive lead in the global electoral college, and are confident about their chances in swing states where polls haven’t yet closed.

In the long-running battle at the ballot box between liberalism and populism, the world map for the populists hasn’t looked this good for some time. They have taken a decisive lead in the global electoral college, and are confident about their chances in swing states where polls haven’t yet closed.

Most significantly, of course, this week the populists eked out a win in the United States, recapturing what had recently been considered a stronghold for the liberals. Many questioned the wisdom of running Donald Trump, a reality-TV star known for his profanity, as candidate for leader of the world’s largest economy, but his promise of a “Brexit plus plus plus” after June’s referendum win in the United Kingdom proved shrewd.

Already reeling from the loss of Britain, liberals were completely blindsided by Trump’s victory. The comfort that came from liberal candidates gaining or maintaining power over the past year elsewhere in the Americas—Argentina, Brazil, and Canada—didn’t last long.

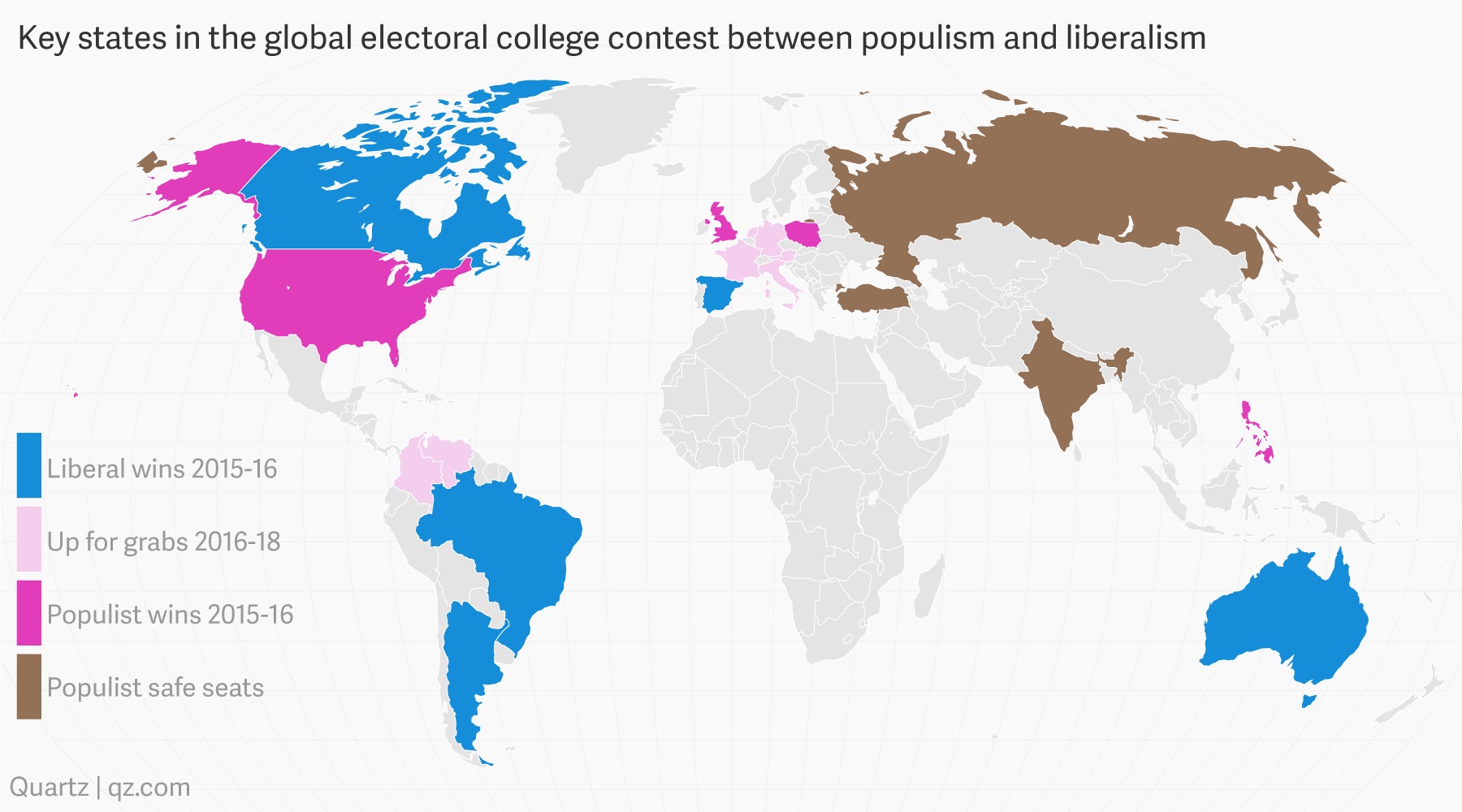

Victories in the US and UK set up the populists for a strong run at swing states that until recently looked out of reach. Let’s take a look at the map:

The liberals, following messy victories this year in Australia (a slim majority) and Spain (a shaky minority), are on the defense, working to repel populist surges all over the map.

Meanwhile, the safest seats for the populists—including Russia, Turkey, and more recent additions India and the Philippines—look far more secure than the line-up on the liberal side, and that doesn’t look likely to change any time soon. It’s hard to consider any liberal stronghold truly “safe” in the current climate.

The next contests to watch come on “Super Sunday” (Dec. 4), and the populists go in with the wind in their sails.

The re-run of Austria’s presidential election will build on their momentum ahead of more important races; although the largely ceremonial position is low on the list of priorities, a win for Norbert Hofer from the far-right Freedom Party would bolster the ranks of hardline nationalists in power.

On the same day, a referendum on constitutional reforms in Italy will be closely watched. A loss for prime minister Matteo Renzi’s government could trigger a general election, opening the door for populists to recapture the seat in Rome just over five years after the final term of populist hero Silvio Berlusconi. The anti-establishment Five Star Movement is ahead in the polls—its rallying cry, according to founder Beppe Grillo, is “We are the barbarians!”

Next year is crunch time for the populists in Europe, as they mount a three-stage challenge on the continent, each more important than the last. In March, votes in the Netherlands will be counted, and we’ll see if the minor matter of a hate-speech trial against populist standard bearer Geert Wilders turns off voters, or energizes them.

The populists’ most winnable prize, perhaps, is France, which tallies its votes for president in April and May. The National Front’s Marine Le Pen is drawing support from similar constituencies as Trump, with a parallel platform espousing protectionism, nostalgia, and cozier Russian relations. “It’s not the end of the world, but the end of a world,” she said as she celebrated Trump’s triumph. “Today the United States, tomorrow France!” said her father, party founder Jean-Marie.

The odds are that Le Pen will falter in the second round of the country’s two-stage runoff vote, as her father did in 2002, but who takes the pollsters’ probabilities seriously any more?

It will take that sort of spirit to put in play the populists’ stretch target—Germany—when the votes are collected in September. It all depends on whether Angela Merkel stands for a fourth term, amid some weakening in opinion polls for the otherwise popular chancellor. If the earlier elections go the populists’ way, Merkel will be squeezed from all sides—Austria, the Netherlands, and France in addition to Poland last year—and may decide that she cannot shoulder the responsibility of leading the liberal democratic establishment on her own. Then again, it’s hard for an upstart party with neo-Nazi tendencies to succeed in a place that was once ruled by actual Nazis.

Further out, in 2018, the populists now believe Colombia may be in play, buoyed by the shock rejection of the peace accord with guerrillas last month. This would put a dent in the liberals’ “southern strategy,” which is having a hell of a time unseating Nicolas Maduro, despite his unpopularity, in the long-time target seat of Venezuela.

The liberals’ other targets are hardly worth putting on the map, so low are their odds of success. For his legal troubles, the chances of toppling Jacob Zuma in South Africa before his term ends in 2019 look remote. The failure of Viktor Orbán’s anti-immigration referendum in Hungary earlier this year also gave liberals some hope of making unexpected inroads in 2018 in a country long considered safe for the populists.

This week, the Hungarian proponent of an “illiberal state”—a 2014 pledge pilloried at the time, but prescient today—dismissed his challengers as advocates of “liberal non-democracy.” Trump’s victory is akin to the “big bang,” he said, “a historic event in which Western civilization appears to successfully break free from the confines of an ideology.”