Crisis-burdened Spain and Cyprus are hot spots for women to sell their eggs

Egg donations thrive off the young and desperate. For years, US college campuses have been plastered with signs imploring young women to “donate” their eggs—for $8,000. More recently, the number of women selling their eggs (and men their sperm) soared amid the recession and high unemployment.

Egg donations thrive off the young and desperate. For years, US college campuses have been plastered with signs imploring young women to “donate” their eggs—for $8,000. More recently, the number of women selling their eggs (and men their sperm) soared amid the recession and high unemployment.

Now, because of permissive laws and cash-strapped young women, Cyprus and Spain have become booming centers of egg donation and in vitro fertilization.

Countries elsewhere in Europe more closely restrict the business of fertility. So hopeful mothers turn to donors in Spain and Cyprus, heralded as destinations for IVF because of lower costs and quicker turnaround times. According to a 2010 story in Fast Company, prospective parents can receive an egg two weeks after request in Spain versus two years in the UK because of restrictions. In the US, the entire procedure can cost upwards of $40,000 compared to $8,000 in Cyprus.

Other rules of economics are at play: There’s a high demand for eggs and they are in short supply. But it’s controversial for women to receive payment for their eggs. Thus, women receive compensation for their time and inconvenience, not for the actual eggs they are giving up. And they are euphemistically called “donors,” so everyone actually feels better about the transaction.

A recent piece in Spiegel tells the story of Spanish women who, when faced with foreclosure, decided to become egg donors. In less than two years, one woman donated 14 times and earned around €10,000 keeping her family from falling into poverty. Spain is wracked with a real-estate crisis and astronomical unemployment but medical tourism, and egg donation in particular, is thriving. From Spiegel:

Private clinic Institut Marquès likewise advertises at universities, targeting its message to young donors and appealing to their desire to help others with the slogan, “What you don’t give will be lost. Even your eggs.”

Cyprus has an especially high egg donation rate: one in 50 women between the ages of 18 to 30. In 2011, Cyprus had more fertility clinics per capita than anywhere else in the world. It’s often immigrant women who are attracted to the practice by handsome pay and no other legal means of acquiring work.

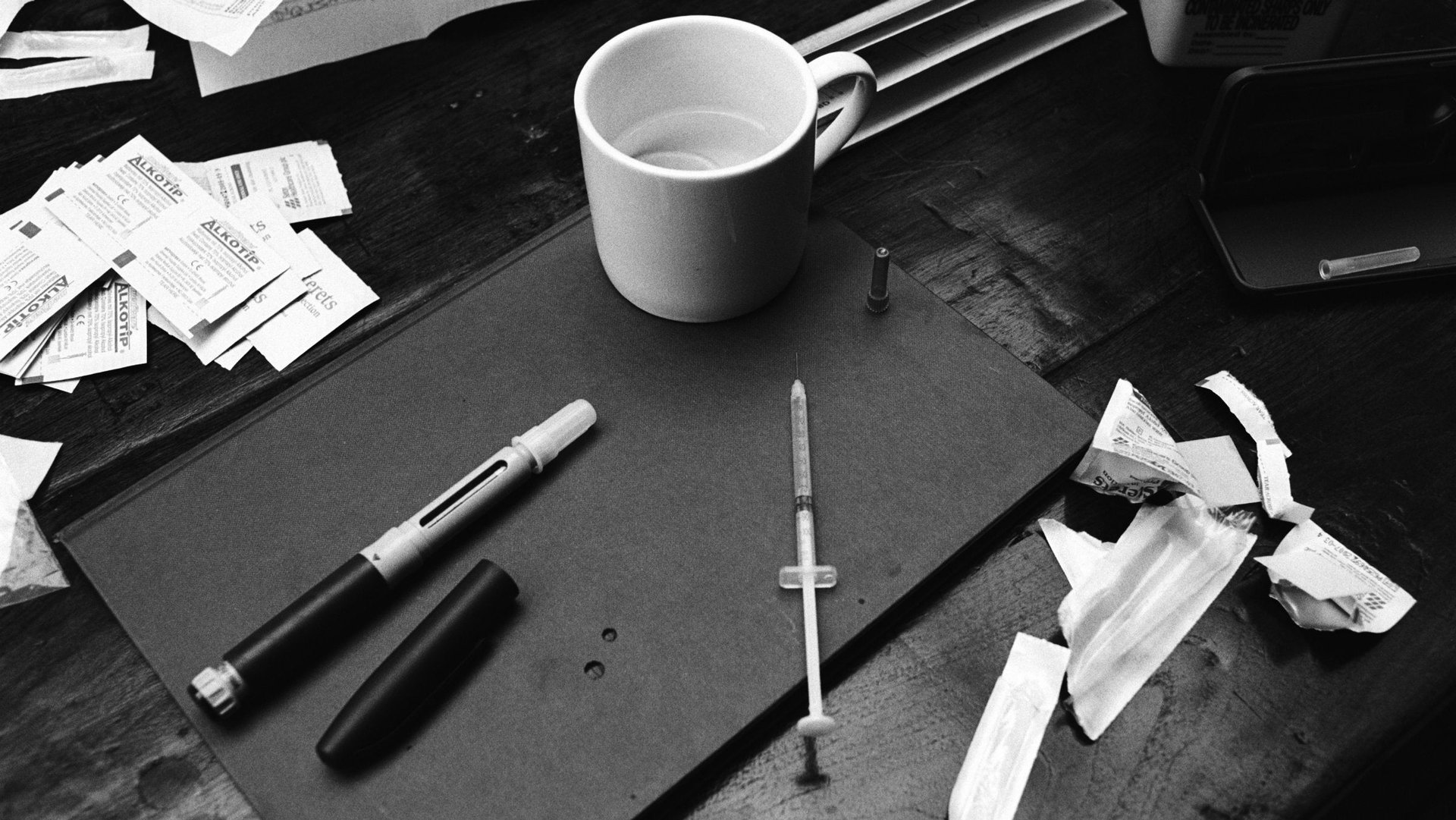

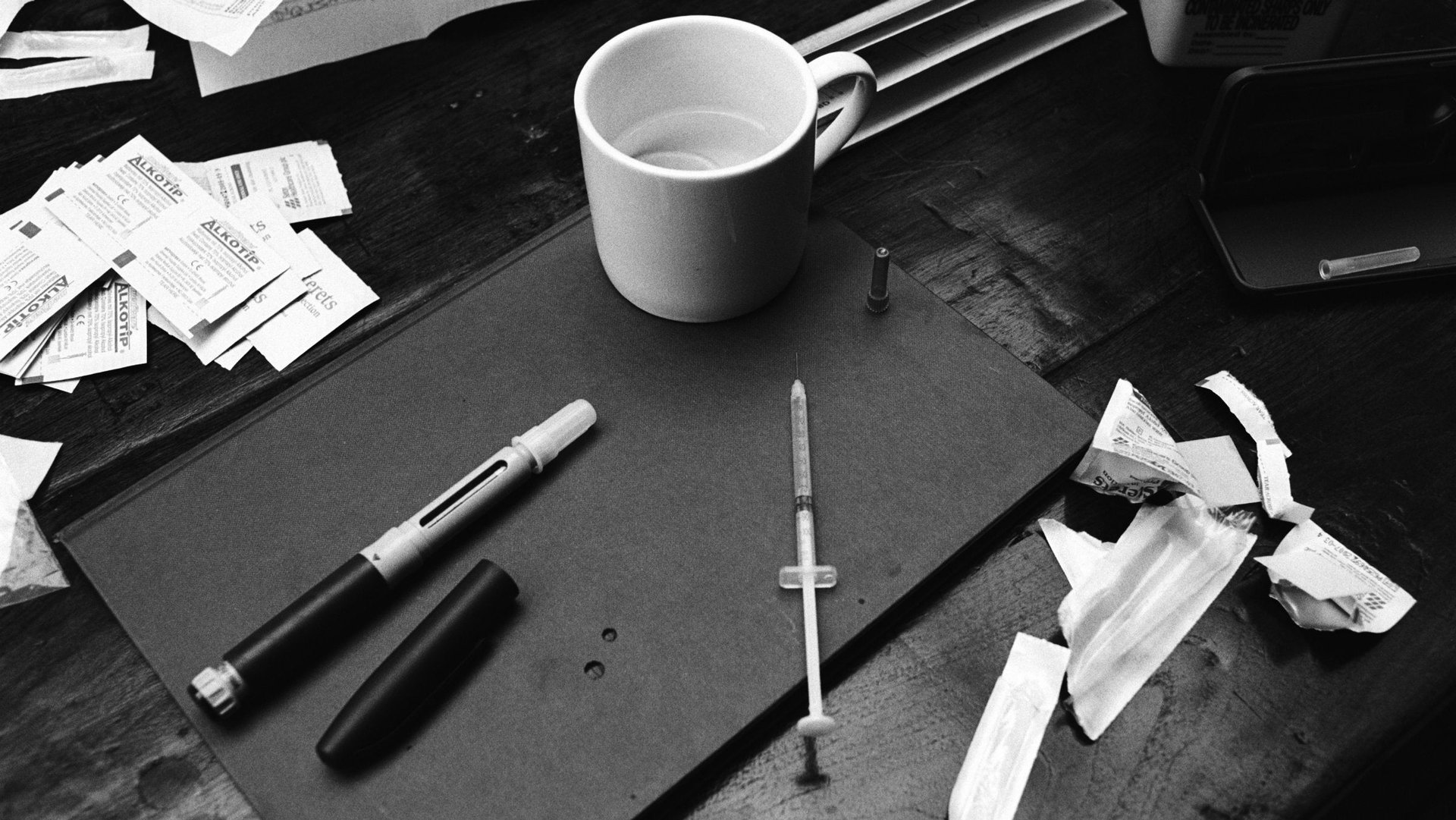

Like reproductive outsourcing in India, the egg donation business preys upon financially desperate women who have little recourse for health risks linked with egg donation. And the risks are plentiful: There’s ovarian hyper-stimulation syndrome in an estimated 0.5 to 5% of women, which can lead to stroke or sometimes death. Other women experience enlarged ovaries and a heightened risk of cancer as well as premature menopause and infertility.

With a hodgepodge of regulation and no central policing body, women donate beyond legal limits in order to keep getting paid. For instance in Spain, a maximum of six children can be born from one donor but because there’s no national registry, women are able to donate to various clinics.

Country to country, the profile of women who sell their eggs and wombs are largely the same. They put their own reproductive health at risk to allow fellow women, at least those who can afford it, to spawn life.