Are cities better off without vehicles? Experiments are underway in France, Germany, and the US

Cities, even those from the earliest of civilizations, are defined by a density of human bodies and interactions. Cars have significantly influenced the design of cities since their advent in the beginning of the 20th century: car culture was celebrated, roads were built, and space for parking cleared. The invention and commercial ascendancy of the personal automobile has shaped (and still impacts) human behavior and city life: parking lots, garages, traffic, and stoplights are among the accoutrements and symptoms of cars, and they at times interrupt parts of cities where people might otherwise connect with one another.

Cities, even those from the earliest of civilizations, are defined by a density of human bodies and interactions. Cars have significantly influenced the design of cities since their advent in the beginning of the 20th century: car culture was celebrated, roads were built, and space for parking cleared. The invention and commercial ascendancy of the personal automobile has shaped (and still impacts) human behavior and city life: parking lots, garages, traffic, and stoplights are among the accoutrements and symptoms of cars, and they at times interrupt parts of cities where people might otherwise connect with one another.

With a growing awareness of global warming, linked directly to the emission of fossil processes, mobility technologies are being revisited. Governments continue to set mandatory emission reduction targets for vehicle manufacturers, but a typical passenger vehicle still emits 4.7 metric tons of carbon dioxide per year, according to the US Environmental Protection Agency. The European Environment Agency measures output differently, and in the EU, cars emitted on average 123.4 grams of carbon dioxide per kilometre—2.5% more efficient than the vehicles sold the year before. It’s no secret these carbon emissions translate into intense smog. The World Health Organization estimates that 80% of city-dwellers live in environments with unsafe levels of pollution.

In reflection of the environmental impacts of traditional fossil fuel burning processes—including cars—new concepts and modes of urbanization and mobility are emerging that will directly affect the planning of and living in the urban realm. City planners and corporations alike have gotten wise to the idea that dense urban areas might better thrive within a society that focuses on a circular economy for a more sustainable life and work style. This has lead to new concepts—with active support from the automotive industry—as alternatives to individually-owned cars. But people are loath to relinquish their cars, and as of 2014 there were 1.2 billion cars on the roads. So cities and organizations will need to coax drivers away from the habit by making the alternatives more appealing.

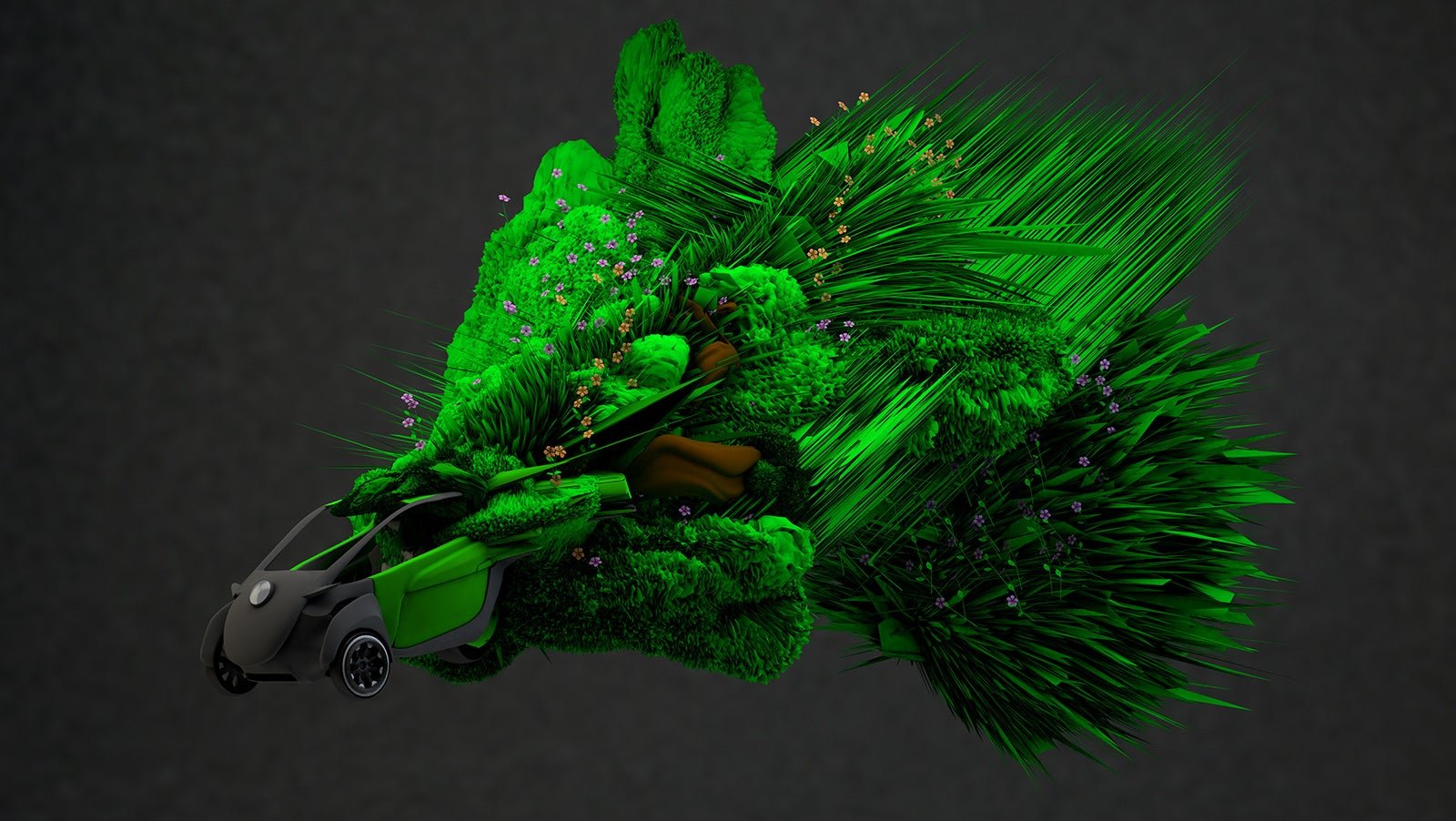

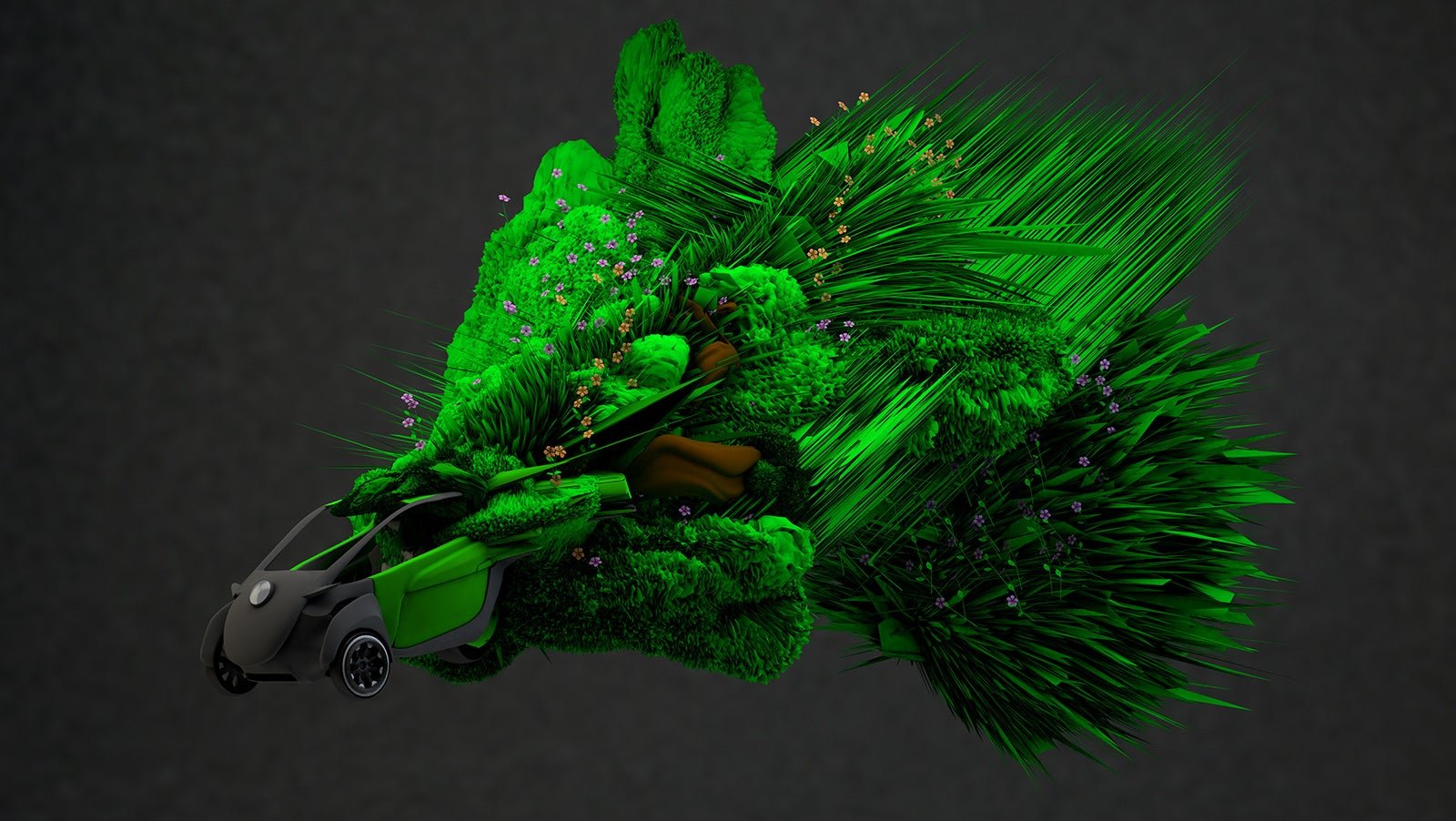

In Grenoble, France, Toyota is sponsoring Cité Lib Ha:mo, a car-sharing service that provides locals with a suite of tiny electric vehicles stationed all around the city. The program has all the hallmarks of a truly modern transportation system: car-sharing exists in other cities, and Cité Lib’s network includes 70 of the Toyota i-ROAD three-wheel vehicles. These are so small they include a two-wheel riding technology called Active Lean that makes driving them a little bit like skiing. Users can pick them up and leave them almost anywhere, because other users need only download the Cité Lib app to find and reserve a vehicle.

The initiative launched in September 2014. Rody El Chammas, the Project Manager from Toyota Motor Europe’s France bureau, says it seems to going well. “It started very small, but it’s growing up,” he says. “This kind of car-sharing is quite innovative.” El Chammas recently compiled a two-year progress report on the project, and found that 92% of the Cité Lib users reported satisfaction. Two interesting statistics emerged from the survey: (1) The average user is 36 years old, and (2) 43% of users combine their Cité Lib subscription with public transportation like trains and buses. The first suggests that young people are adopting new habits, ones that don’t hinge so closely on the comfort of a personal vehicle. The second backs up something El Chammas says, about the symbiosis of car-sharing with other modes of public transportation. “When you have public transport some people might think it’s competing [with other options],” he says. “But without public transport it’s difficult to introduce this kind of service. Complementary service is needed.” That alone is a path to cleaner cities.

Experiments in some other cities skew more extreme, and ban cars outright. Take Barcelona’s superilles mobility plan. Superilles, or superblocks, consists of around nine blocks that, once repurposed, will belong solely to pedestrians and cyclists. In this vision ecologists can plan for more green space—a crucial element to keeping city-dwellers healthy and active. The city of Barcelona hopes the plan will cut down on local car usage by 21%. Further north, Oslo has announced plans to ban personal cars entirely from the city center, in an effort to cut down on greenhouse gas emissions. These are clever but timid beginnings. Planners of newly built so-called “cities of the future” like Masdar near Abu Dhabi can account for public transportation and electric vehicles from the very start, making subways the new highways, and electric charging stations vital and not an afterthought to gas stations. But existing cities have to retrofit.

In a sense, that’s what New York City did with its recent “Shared Streets” initiative. The experiment routed cars away from the streets of Lower Manhattan for select periods of time, as short as single afternoons. That part of New York is an ideal test bed: Lower Manhattan’s cramped, European-style streets were built before taxis and Uber drivers had to shuttle professionals to the tip of the island. That design means highly congested traffic and average driving speeds of just 8 miles per hour. “What makes Manhattan unique is its unparalleled, walkable streetscape—but it is still so often dominated by cars and traffic,” said Manhattan Borough President Gale A. Brewer, in a press release from the New York City Department of Transportation (DOT). “Programs that transform our streets into walkable public spaces offer a truly special opportunity to experience the city in a whole new way.”

Free of all those cars, pedestrians and store owners in Lower Manhattan were free to move around and interact more. Through time lapse videos and surveys, the DOT can determine if those interactions signal that the area is better off without vehicles. It’s not always obvious. Fewer cars could mean fewer new people to stimulate the local economy. Each new experiment faces some kind of logistical challenge like this. In Grenoble, El Chammas says the Cité Lib team is still watching and learning. He knows that the number of the Toyota i-ROADs and readiness of charging stations are paramount to getting consumers onboard.

Citizens’ feelings about shared, public transportation is as good an indicator as any that a city has achieved clean, affluent living. In the words of Enrique Penalosa, former mayor of Bogota: “An advanced city is not one where even the poor use cars, but rather one where even the rich use public transport.”

To discuss this and other topics about the future of technology, finance, life sciences, and more, join the Future Realities LinkedIn group, sponsored by Dassault Systèmes.

This article was produced by Quartz creative services and not by the Quartz editorial staff.