The scent of an apple could replace your smartphone’s LOL face

“It is Xiao C,” a recorded voice said. “Do you remember our classmate Xiao Hua? I heard that she is getting married… Her husband was our English teacher in high school!”

“It is Xiao C,” a recorded voice said. “Do you remember our classmate Xiao Hua? I heard that she is getting married… Her husband was our English teacher in high school!”

The message arrived with a fleeting cloud of mint-scented oil, delivered from an inconspicuous white box, a foot or so away from its recipient. Five seconds later, the smell dissipated. Later, another message arrived. This time it was a text, accompanied by a waft of vinegar. It read: “Ha, you are jealous because she married Liu.”

The message recipient was one of 54 people recruited for in a Chinese study that looked at whether emotions could be expressed with scent during digital communication—a concept the researchers call “odor emoticon.”

The study, published April in The International Journal of Human-Computer Studies, involved a three-phase process in which separate groups of participants selected, reviewed, and corresponded with one another using scents. The researchers—three from Zhejiang University and one from the MIT—found that smell-enhanced chatting was intuitive, encouraged more communication, and helped participants perceive and convey their emotions.

“There is a close physiological connection between olfaction and the system that is responsible for emotional experience,” explains Pamela Dalton, a cognitive psychologist and olfactory expert from the Monell Chemical Senses Center in Philadelphia. “Odors are uniquely emotionally evocative, due to their propensity to become associated to people, places, and internal states—it’s a very powerful way to communicate beyond what we see and hear.”

Despite its power of induction, however, odor has yet to really be incorporated into mainstream technology. Dalton attributes this largely to the difficulty of replicating the hundreds of thousands of the world’s complex odors. But MIT professor Michael Bove, one of the study’s authors, argues that olfaction has simply been “less researched in human-computer interaction than it deserves.”

The biggest olfaction study to date is a 1986 National Geographic survey, in which 1.5 million subscribers “scratched and sniffed” a page of six samples sent to them in the magazine, revealing how age and gender could influence a person’s sense of smell. And while pheromone parties and smell dating services (in which potential lovers swap worn t-shirts) capitalize on studies linking body odor to sexual attraction, olfaction has yet to find its place in the realm of digital communication—where sight, sound, and more recently, touch—such as Apple’s haptic trackpack technology—have become elemental.

But “that’s clearly starting to change,” says Bove, “just here at the Media Lab there are at least three olfaction-related projects going on.” In the first phase of the MIT- Zhejiang collaboration, the researchers surveyed 98 people on which odors they believed best depicted certain emotions. Then, a separate 50-person research group smelled the chosen odors and aligned them with what they believed to be the most accurate corresponding emotions.

“The most surprising finding is that we really got several odor emoticons,” says one of the study’s authors, Zhejiang University professor, Wei Xiang. While previous studies on odor and emotion have linked simple feelings like “pleasantness” and “disgust” with specific smells, this study found that “odor emoticons” might function similarly to visual emojis; repeated use between users codifies symbols that may initially seem ambiguous.

In the end, the researchers came up with nine odor emoticons, including “apple” for “happiness,” “rose” for “love,” and “vinegar” for “envy.”

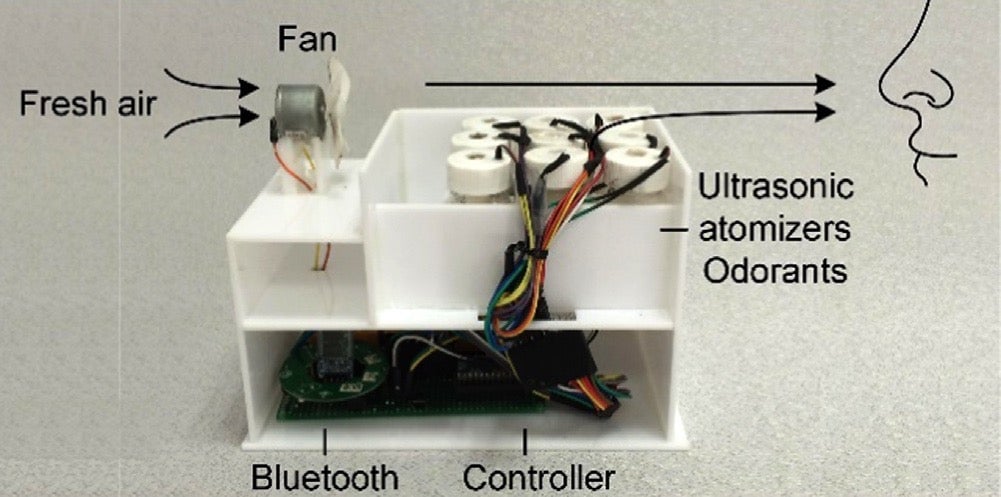

In the final stage of the study, 54 participants were brought on to actually try out the odor emoticons. The researchers first had the participants listen to pre-recorded voicemails while a prototype “Olfaction machine” secreted pre-selected scents from the Demeter Fragrance Library using an air humidifier.

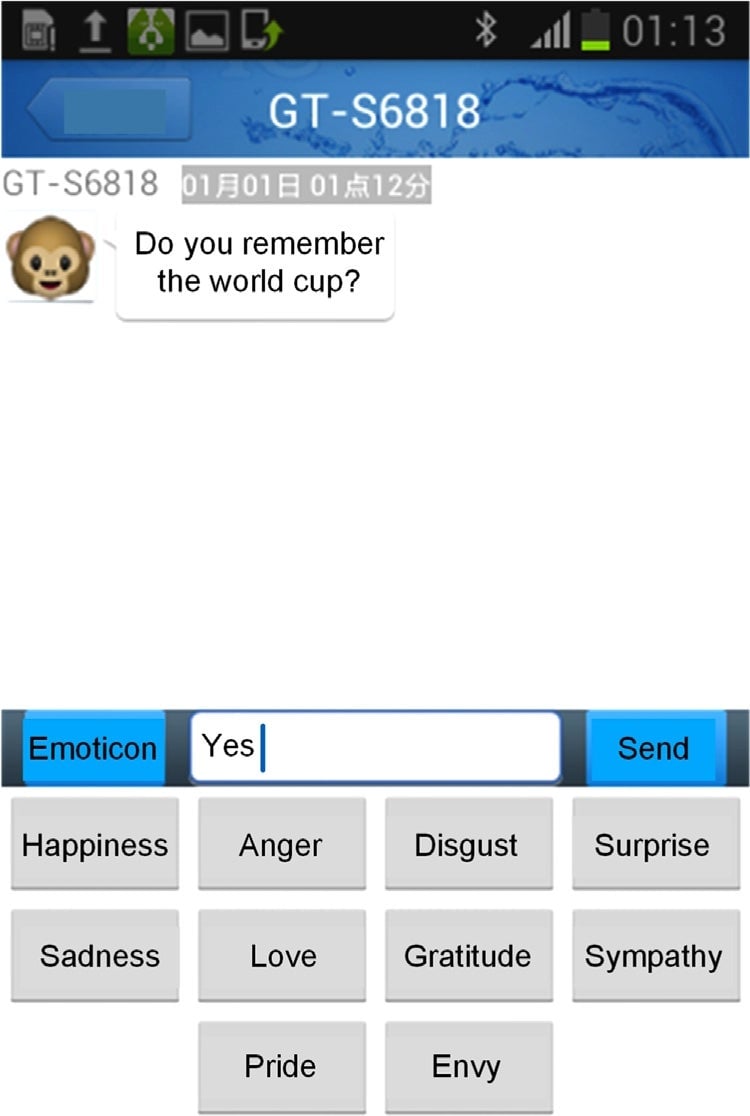

Then they were asked to to communicate (via text) on pre-selected topics like the 2014 World Cup and the 2008 Wenchuan earthquake. While texting, the participants could click a button with a listed emotion which would then trigger the Olfaction machine to emit the matching odor. For example, during a conversation about the Wenchuan earthquake, a participant, recalling a teacher who had abandoned his students during the disaster, chose to emit “anger” (ammonia). Other “odor emoticons” available included “pride” (ink), “envy” (vinegar) and “love” (rose).

The most frequently chosen emoticon was “happiness” and the least common was “envy.”

Following the experiment, most participants reported it was easy to match odors with corresponding emotions, that they had enjoyed using them, and found them easy to incorporate into conversation. Based on these responses and increased chatting frequencies when odor emoticons were being used, researchers concluded that smells could potentially be used to enhance users’ implicit understanding of the emotional content of messages.

They stressed, however, that the study was really just an early-stage test to understand the potential for olfaction in human-computer interaction. One major pitfall is that the study was very culturally relative: many of the odor-emotion links discovered in the project are bound specifically to the Chinese experience. For example, while this study tied “apple” to “happiness,” a 1999 French paper showed that lavender was most likely to elicit the same emotion among French participants. Eventually, experiments will have to be done all over the world in order to develop culturally-specific odor emoticon vocabularies.