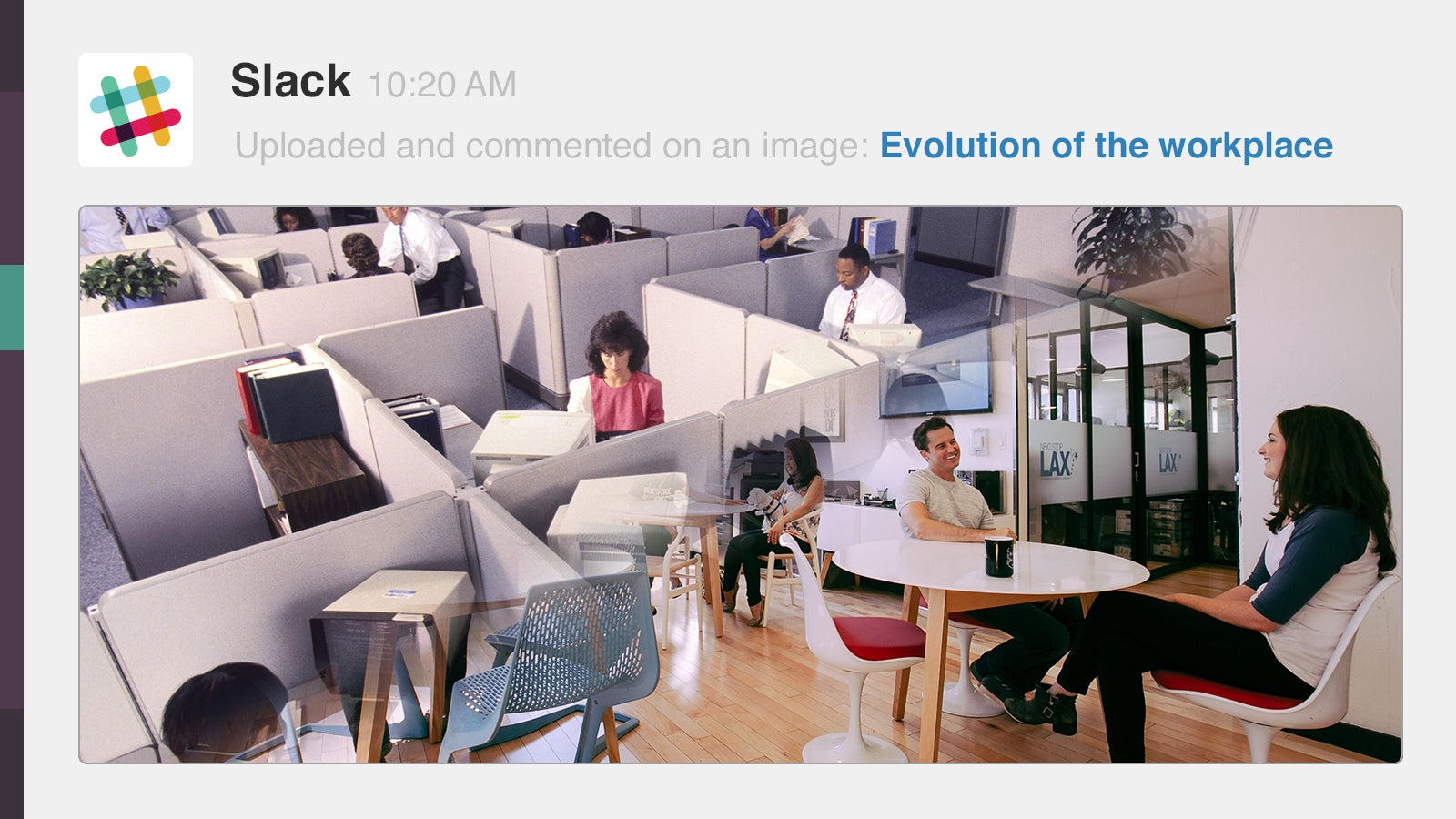

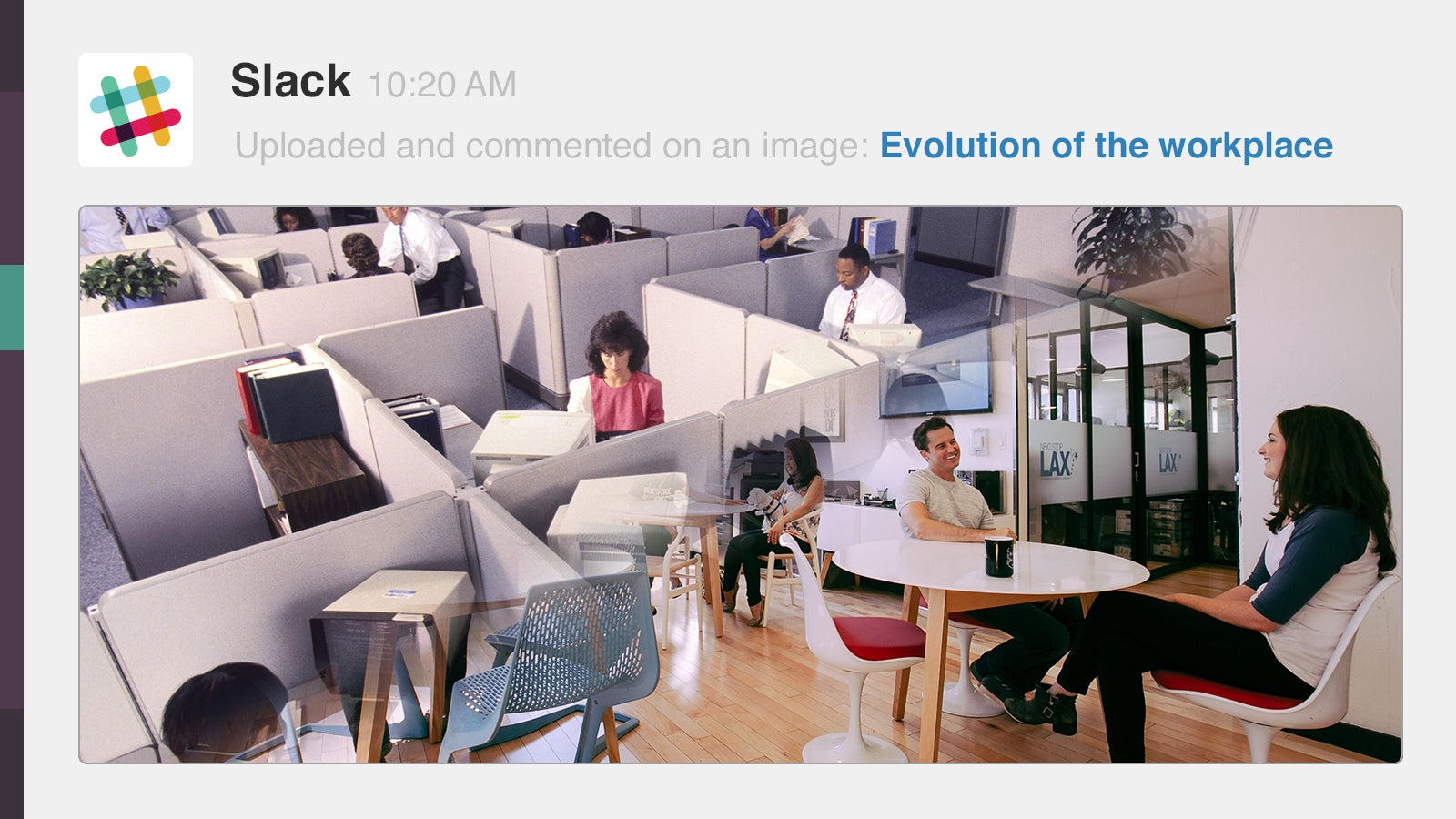

A short history of the office

Nikil Saval, author of Cubed: A Secret History of the Workplace, sits down with the Slack editorial team to talk about the ever-evolving design of workplaces.

Nikil Saval, author of Cubed: A Secret History of the Workplace, sits down with the Slack editorial team to talk about the ever-evolving design of workplaces.

What did early offices look like and what kind of work did the first office workers do?

Mid-century early offices were small, one-room affairs with two to three clerks, a partner, and a bookkeeper. Office work wasn’t seen as especially distinct or interesting, and consisted of endless copying of documents.

In

Cubed

, you introduce us to Robert Propst, who in 1960 became president of

Herman Miller

’s research practice. How did his Action Office concept lead to the creation of the cubicle?

In the 1960s, offices had rows of desks that looked like paperwork assembly lines in factories. Robert Propst, an employee of Herman Miller furniture company, felt this arrangement was entrenched in hierarchy and status. He reacted against it, creating the Action Office, a three-walled, hinged space, meant to be open and flexible. That’s why it was called Action Office: it was for movement. Launched in 1968, it was widely embraced. Companies copied it, and consequently the ideas of action and movement were lost. They took his design and cubed it.

What are some of the most important developments in office culture in the two years since your book came out?

There are two trends that have continued. One is the increasing “gig-like” nature of work. This leads to higher levels of inequality: some are super freelancers and others are struggling. Along with it is the growth of coworking and its professionalization. When I was looking into coworking spaces, most were tiny, ad-hoc spots. Now there are established coworking companies like WeWork. The result is a lot of organizations who aren’t devoting resources to permanent office space, and freelancers who choose coworking spaces because they are afraid of isolation.

How do you see these trends affecting work culture and productivity?

Productivity is a hard thing to measure. It’s not easy to work in coworking companies because many are open and noisy. They are more about connecting people; to do work, you have to find a quiet space within the coworking space. One promising thing is that there are lots of third spaces in cities, such as cafes and libraries. There is this increasing permeability between the office and the city.

What does the ideal workplace look like to you?

The thing that unites all these examples is that the office worker is totally free to choose—a worker has the power to determine his or her working arrangement. Looking at it from the perspective of a worker’s needs is the better way of looking at the workplace.

This piece is part of a series examining the contemporary workplace, originally written by the Slack editorial team. For more stories from Slack, visit their blog, Several People are Typing.

This article was produced by Slack and not by the Quartz editorial staff.