For both China’s rich and the poor, it wouldn’t be Lunar New Year without the long journeys

One of the biggest annual celebrations around the world is upon us: Jan. 28 marks the start of the Lunar New Year. Also known as the spring festival, it is the most important holiday in the Chinese calendar, akin to Christmas in the West. An important time of family reunions and catching up with old friends, it is also a huge consumer holiday.

One of the biggest annual celebrations around the world is upon us: Jan. 28 marks the start of the Lunar New Year. Also known as the spring festival, it is the most important holiday in the Chinese calendar, akin to Christmas in the West. An important time of family reunions and catching up with old friends, it is also a huge consumer holiday.

Spending during the season in 2014 on shopping and dining was around 610 billion yuan—about $100 billion. This is almost double the amount American shoppers spent over the Thanksgiving weekend in 2015. The festival is celebrated by everyone and, in a country of extreme wealth that is also home to 7% of the world’s poor, the way that it is celebrated varies greatly.

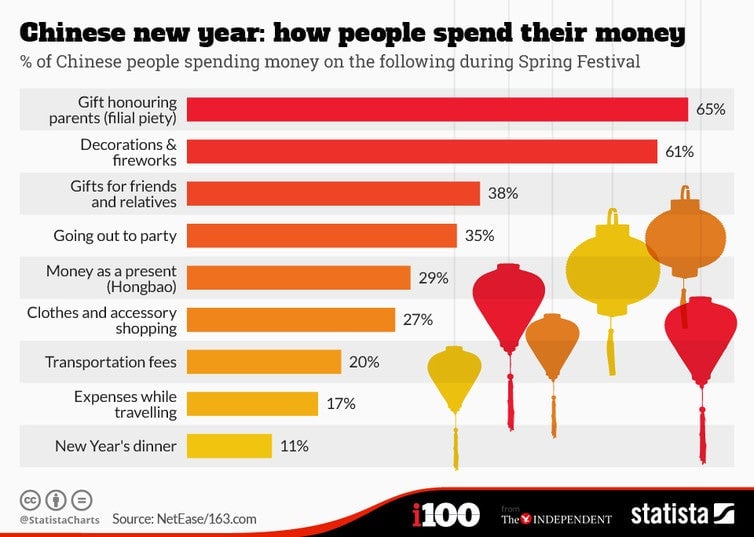

There are a few things that all Chinese citizens have in common though. Most buy gifts for their parents and elderly family members, and 65% of respondents in a survey in 2015 showed that clothes were a favored item. Other significant areas of spending are decorations and fireworks, party goods, transportation costs, and new year’s dinner. Another spring festival custom is to give friends and relatives money in red envelopes, known as hong bao, for good luck. China’s internet companies began to capitalize on this in recent years, with the popular messaging app WeChat launching a way to share money through messaging.

The long journey home

No matter how far away family members may have migrated across China, they are expected to make the journey home during Chinese New Year. As a result, the holiday is believed to be behind the largest movement of people in the world. Up to 2.91 billion trips were estimated to be made in 2015 via road, railway, air, and water—up 3.6% from the previous year, according to the National Development and Reform Commission, the country’s top economic planner.

Spare a thought for the 100,000 migrant workers stuck in the Guangzhou train station in the heart of China’s manufacturing region due to train delays, as they try to make their long journey home for the holiday.

Migrant workers are the backbone of China’s low-cost and labor-intensive economy. They make up an estimated 278 million workers who have migrated from rural parts of China to work in the big cities and for many, Chinese New Year is their only holiday. It’s often the only chance they have to spend some time with their entire family, including children left with grandparents who take care of them.

Migrant workers also bring home their hard-earned cash, which is vital to the local rural economy. Earnings from the big cities enable families to move into new and better homes, send their children to school, and purchase livestock and other things, such as new flat screen TVs.

The other half

A growing number of wealthier Chinese opt to avoid the new year chaos and social obligations by traveling abroad for their holidays. In 2015, 5.2 million left mainland China over the holiday. The most popular destinations are other countries in East Asia, as well as the US and Australia.

Chinese tourists are well known for spending big abroad. China is the biggest outbound tourism spending country, with vast amounts spent on luxury goods. Many Chinese consumers consider foreign products to be of superior quality and better designed than their domestic competitors—Hermès handbags, Burberry trench coats, and Patek Philippe watches are often top of Chinese tourists’ shopping lists.

In 2015 Chinese consumers spent more than $100 billion on luxury goods, accounting for 46% of the world’s total. Around 80% of these sales are made abroad. Attracted by the weaker euro and Japanese yen, Chinese consumers are increasingly opting for Europe and Japan, instead of their traditional shopping hotspots of Hong Kong and Macau.

So as well as seeing the largest migration of its citizens as they crisscross the country, Chinese New Year sees a surge in spending by its elites both inside and outside of China. This feeds into the crucial shift the country is making from having an economic growth model driven by manufacturing to one based on consumption and services, of which tourism and entertainment are crucial elements.

This post originally appeared at The Conversation. In-post image made available under Creative Commons License CC BY-NC-ND 4.0.