The liberal backlash against “identity politics” blames Trump’s win on those most vulnerable to Trump

Over the past two weeks, pundits from all ends of the spectrum have been scrambling to explain Hillary Clinton’s unexpected loss in the US presidential race, with reasons spanning from the plausible to the highly dubious; WikiLeaks, Bernie Sanders, fake news, Jill Stein, Russia, bad algorithms, and the FBI have all been accused of having sole or part responsibility. Lately, however, a new, entirely bogus culprit has emerged from center and center-left circles: “identity politics” and its close cousin, “political correctness.”

Over the past two weeks, pundits from all ends of the spectrum have been scrambling to explain Hillary Clinton’s unexpected loss in the US presidential race, with reasons spanning from the plausible to the highly dubious; WikiLeaks, Bernie Sanders, fake news, Jill Stein, Russia, bad algorithms, and the FBI have all been accused of having sole or part responsibility. Lately, however, a new, entirely bogus culprit has emerged from center and center-left circles: “identity politics” and its close cousin, “political correctness.”

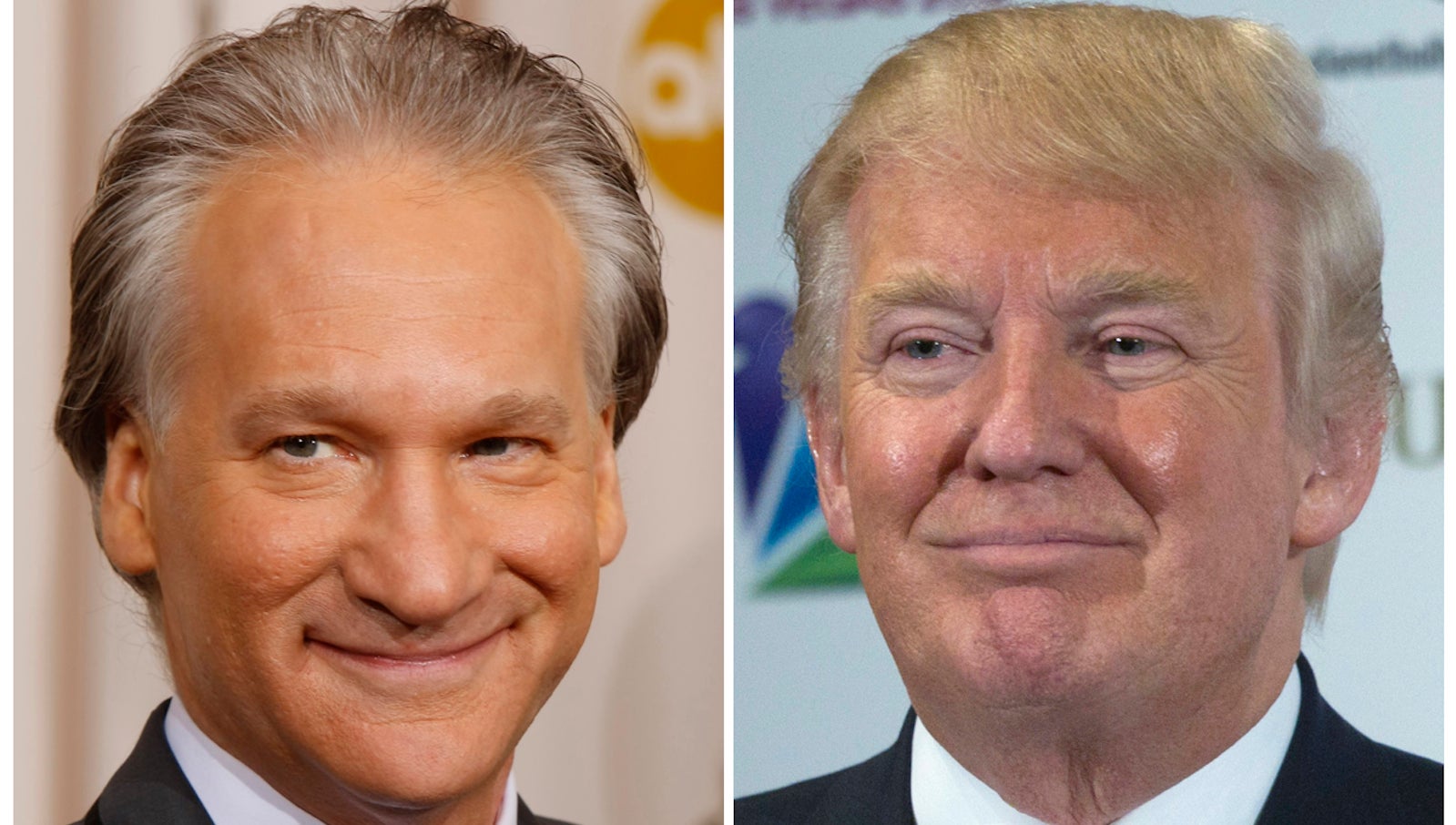

It began days after the election, when evergreen political correctness-hater Bill Maher lashed out at “political correctness” for Trump’s win, based on what appears to be a gut feeling he had:

You’re outrageous with your politically correct bullshit and it does drive people away. And Islam. You know? Islam. Democrats, there is a terrorist attack, and Democrats’ reaction is “don’t be mean to Muslims,” instead of how can we solve the problem of shit blowing up in America. And, you know, that’s not a good way to get votes.

Even by the standards of TV blowhards, little argument was offered. Maher, like the others advancing this trope, just took his pre-existing hang-up—in his case, what he sees as liberal coddling of Muslims—and projected it onto the electorate. Since Trump sold himself as “politically incorrect,” it logically follows that some original PC leftist sin helped fuel his rise.

Two days later, Vox would run a softball interview with Jon Haidt, a noted NYU social psychologist and diversity skeptic, headlined “Why Social Media Is Terrible for Multiethnic Democracies. ” Vox editor Ezra Klein teed up by tweeting, “Interesting: Jon Haidt on why ‘diversity, immigration and multiculturalism’ are ripping apart Western democracies.” Clouded in academic trappings and qualifiers, Haidt advances some fairly toxic victim-blaming:

Multiculturalism and diversity have many benefits, including creativity and economic dynamism, but they also have major drawbacks, which is that they generally reduce social capital and trust and they amplify tribal tendencies.

The academic basis for such a claim aside, Haidt has made a leap from “multiculturalism and diversity” to the specific instance of Trump’s election, based on vague notions of “amplified tribal tendencies.” Who helps amplify those tendencies, and who profits from our history of white “tribalism,” isn’t broached, much less dissected. It’s simply an inevitable law of sociology, and no one—save, of course, the minorities guilty of “identity politics”—are held liable. Haidt continued:

A multiethnic society is a very hard machine to assemble and get aloft into the air, and if you get it just right, you can get a multiethnic society to fly, but it easily breaks down. And identity politics is like throwing sand in the gears.

Politics is always about factions, always about competing groups. At the time of the founders, those groups involved economic interests—the Northern industrialists versus the Southern agrarians and so on.

But in a world in which factions are based on race or ethnicity, rather than economic interests, that’s the worst possible world. It’s the most intractable world we can inhabit, and it’s the one that will lead to the ugliest outcome.

Interviewer Sean Illing lets these highly contestable, downpunching claims go unchallenged, namely the false dichotomy asserted by Haidt—and one very common in this backlash—that economic populism and identity politics are somehow mutually exclusive.

This, of course, isn’t true. Advancing economic populism while understanding that particular groups have specific concerns—such as freedom from discrimination—has always been a mainstay of left politics. Those insisting it has to be either/or likely care about neither, and are content maintaining the status quo.

This was followed by three anti–identity politics pieces published on the same day in the two leading centrist establishment newspapers:

- “The Danger of a Dominant Identity” (David Brooks, New York Times, 11/18/16)

- “Higher Education Is Awash with Hysteria. That Might Have Helped Elect Trump” (George Will, Washington Post, 11/18/16)

- “The End of Identity Liberalism” (Mark Lilla, New York Times 11/18/16)

Brooks began by positioning a strawman: that “pollsters reduced complex individuals to a single identity” and assumed they would all vote accordingly:

Pollsters assumed women would vote primarily as women, and go for Hillary Clinton. But a surprising number voted against her. They assumed African-Americans would vote along straight Democratic lines, but a surprising number left the top line of the ballot blank.

The pollsters reduced complex individuals to a single identity, and are now embarrassed. But pollsters are not the only people guilty of reductionist solitarism. This mode of thinking is one of the biggest problems facing this country today.

But Brooks never cites a single pollster that actually did this—likely because none did. Pollsters argued that certain groups would have a greater or lesser tendency to vote for Clinton, not that they any would vote uniformly. Never mind, though—Brooks has a pre-existing grievance with identity politics, and showing it somehow tricked pollsters is essential to contriving this grievance into his piece.

In typical Brooks fashion, he went on to equate anti-racism with racism: “But it’s not only racists who reduce people to a single identity. These days it’s the anti-racists, too. To raise money and mobilize people, advocates play up ethnic categories to an extreme degree.”

To fight back, people targeted by racists occasionally “raise money and mobilize people” who, like them, are also targeted by racists. The horror! “Why isn’t there a White History Channel?” inanity has its most influential booster, and he’s a bespectacled “moderate” at the New York Times.

George Will, whose piece is too lazy to examine in depth, does what George Will has been doing for 30 years: He lists off some anecdotes of ostensibly goofy political correctness, then tacks on a half-assed concluding paragraph about how it “might have” led to Trump.

Mark Lilla’s op-ed is much longer and far more pernicious. The Columbia historian doesn’t even bother to attach his statements to sociology, instead speaking in solipsistic terms about his own trip to Europe. Like Haidt, he engages in false dichotomy, presenting Clinton’s appeal to blacks and LGBTQ as somehow dismissive of the “white working class:”

But when it came to life at home, she tended on the campaign trail to lose that large vision and slip into the rhetoric of diversity, calling out explicitly to African-American, Latino, LGBT and women voters at every stop. This was a strategic mistake. If you are going to mention groups in America, you had better mention all of them. If you don’t, those left out will notice and feel excluded. Which, as the data show, was exactly what happened with the white working class and those with strong religious convictions.

Lilla provided no evidence, even anecdotally, that the white working class felt “left out.” It’s just something he asserts, but never connects the dots.

He went on to glibly dismiss writing that focused on specific communities, mocking stories about transgender people in Egypt:

However interesting it may be to read, say, about the fate of transgender people in Egypt, it contributes nothing to educating Americans about the powerful political and religious currents that will determine Egypt’s future, and indirectly, our own. No major news outlet in Europe would think of adopting such a focus.

Except one European paper, the Guardian, did adopt such a focus last year (in a wonderful piece everyone should read). Lilla’s screed can’t seem get its straw liberals in order.

Similarly, he laments “high school curriculums” that focused on “the achievements of women’s rights movements” while ignoring “the founding fathers’ achievement in establishing a system of government based on the guarantee of rights.” No evidence is offered of these high schools that have erased the “founding fathers” from history classes, nor is it clear why it’s so urgent women’s rights studies pay due deference to Thomas Jefferson and Co. over the scores of other philosophers who’ve written on the issue of rights.

Others, such as the Des Moines Register’s Froma Harrop (11/15/16), Reason’s Robby Soave (11/9/16) and Damon Linker and Pascal-Emmanuel Gobry, both at The Week (11/16/16 and 11/18/16), also piled on—as did “new atheist” personality David Rubin and popular comedy writer Seth MacFarlane. These 11 high-status observers agreed: The political correctness police fueled the Trump backlash.

There’s only one problem: There isn’t really any evidence provided. No studies proffered, no exit poll dissecting, no empirical basis for this conclusion at all. It’s just a vague feeling, something that seems true. There’s a supposed problem—an excess of political correctness and identity politics—but it’s not connected to the topic at hand: the election of Donald J. Trump.

But let’s be generous. Even if, for the sake of argument, one accepts the premise that “political correctness” fueled Trump’s success, what’s missing from the conversation is that few people—the above pundits not excepted—derive their ideas of political correctness from first-hand experiences.

Often the perception of “political correctness” is heavily filtered through Fox News and right-wing radio’s cartoon version of it. Day in and day out, center and center-right outlets highlight and distort the most obscure excesses, typically on college campuses, to feed a narrative to its audience that white men are under siege by conspiratorial liberal forces. But the majority of Trump’s supporters haven’t been to college in decades, nor are they interfacing first-hand with these academic enclaves; rather, they’re presented with anecdotes on television and a bustling market of anti-liberal films that stoke a vision of a dystopian PC police state.

To this extent, liberals couldn’t really dial down the “identity politics” in an effort to assuage white conservatives even if they wanted to; the Murdochian echo chamber will just move the goalposts and cherry-pick new outrages. Centrists and liberals accepting the premise of out-of-control political correctness as something that can be dialed down have done all of the heavy-lifting for the right wing—and, increasingly, white supremacist forces—without critically analyzing whether the average voter’s perception of “safe spaces” and “thought-policing” is at all connected to objective reality.

Same with immigration, terrorism, and a whole host of right-wing soft spots: They are serious issues, to an extent, but they are racialized and then magnified a thousandfold by a partisan media machine that feeds off and profits greatly from white grievance.

A lack of sufficient economic populism on Clinton’s part is a reasonable critique, and one some of these pundits are perhaps hinting at. But absence of populism isn’t evidence that “identity politics” is to blame; it’s evidence that Clinton’s economic outlook is centrist, and would be regardless of whether she said “black lives matter” or targeted messages to the LGBTQ community.

Every one of the above pundits who is blaming identity politics and political correctness for Trump, it can’t be stressed enough, hated identity politics to begin with, and would have regardless of who won. They’re jamming a long-held dislike into a topical and convenient narrative—an act that could be dismissed as cynical self-flattery if it wasn’t, in the face of an upsurge of reactionary politics, also helping provide ideological cover for racists and demagogues.