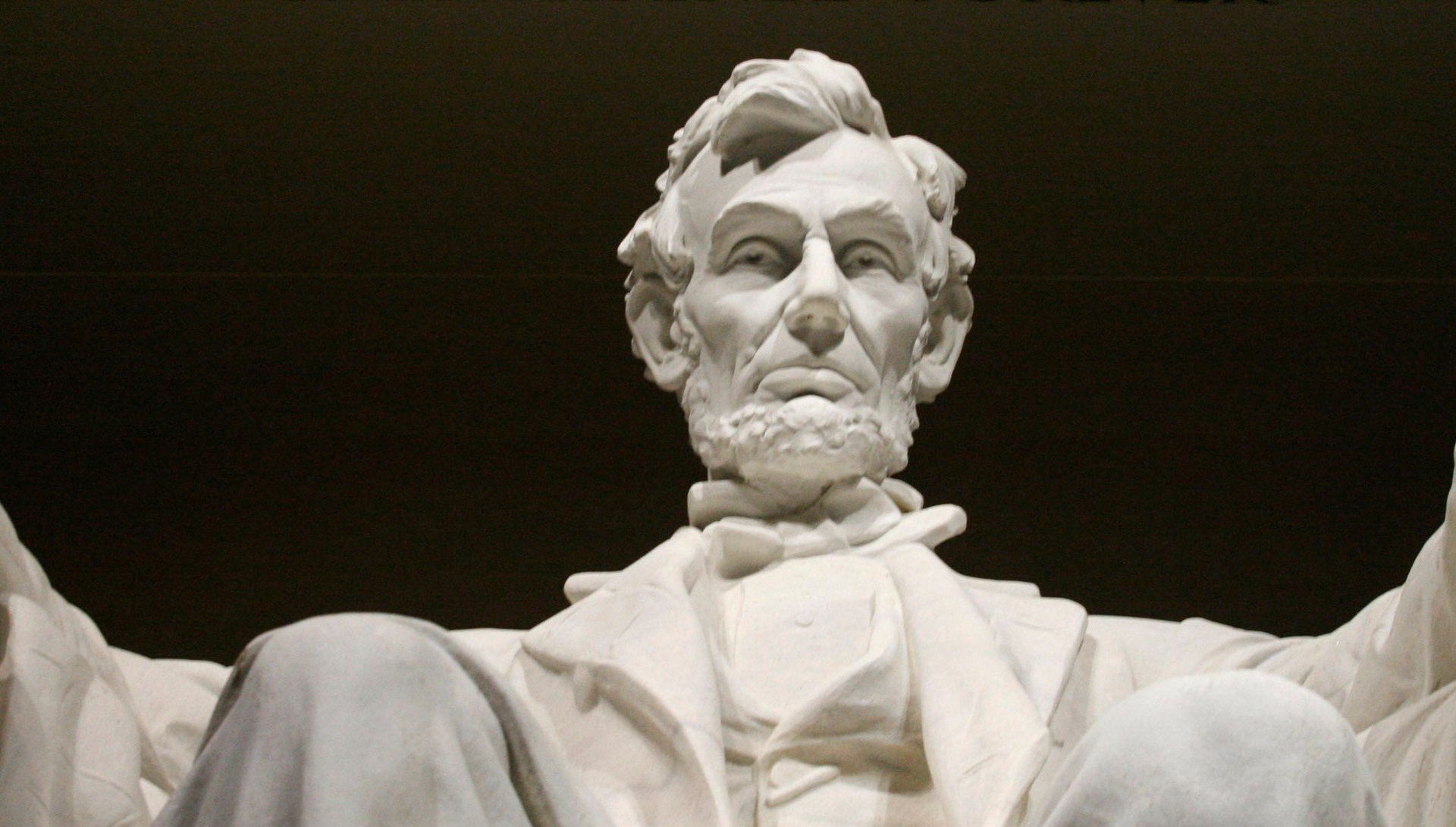

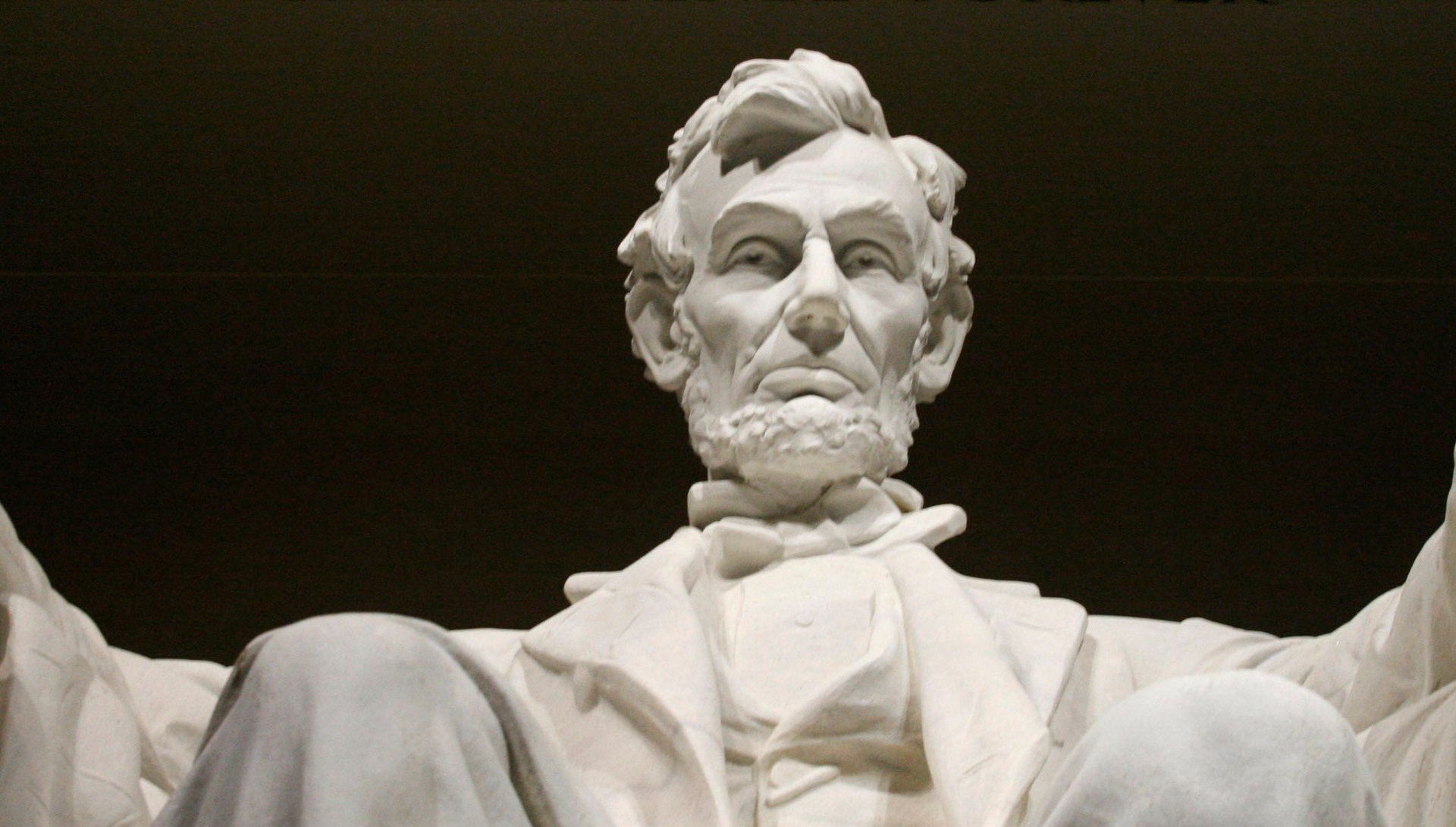

Fake news isn’t a recent problem in the US—it almost destroyed Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln was more than just a foe of slavery. He was also a mixed-race eugenicist, believing that the intermarriage of blacks and whites would yield an American super-race.

Abraham Lincoln was more than just a foe of slavery. He was also a mixed-race eugenicist, believing that the intermarriage of blacks and whites would yield an American super-race.

Or at least, that’s what newspapers in 1864 would have had you believe. The charge isn’t true. But this miscegenation hoax still “damn near sank Lincoln that year,” says Heather Cox Richardson, history professor at Boston College.

In February 1864, Lincoln was preparing for a tough re-election campaign amidst a bloody civil war when he and his Republican party were blindsided.

The attack came from Samuel Sullivan Cox, an Ohio congressman from the pro-slavery Democrats, who gave a fiery speech to Congress condemning Republicans for championing the idea that whites and blacks have children together to create a new “American race,” declaring these views to “have been a part of the gospel of abolition for years.”

Democratic papers around the country reprinted the transcript of Cox’s speech. The Republicans’ “disgusting theories” had gone viral.

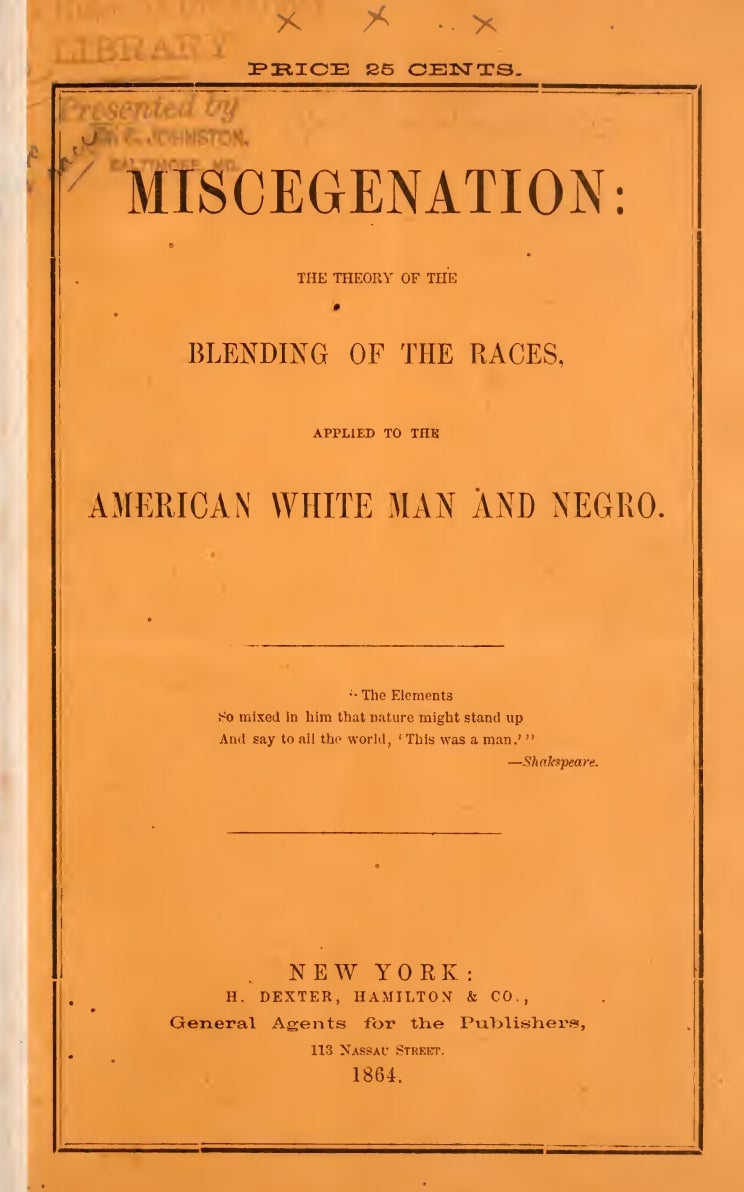

Cox was citing a 72-page anonymous pamphlet titled “Miscegenation: The Theory of the Blending of the American White Man and Negro” that extolled intermarriage of races and encouraged Republicans to openly endorse this philosophy by adding it to their official party platform.

In March, after Horace Greeley, the Republican editor of the New York Tribune, declared marriage the exclusive business of the couple marrying, the Democratic press cranked out more headlines casting Republicans as pro-miscegenation. The “leading Republican journal of the country is the unblushing advocate of ‘miscegenation,’ which it ranks with the highest questions of social and political philosophy,” wrote the New York World, a Democratic paper.

As 1864 wore on, more pamphlets circulated painting Lincoln and the Republicans as advocating intermarriage between the white working class and blacks. Though the scandal dogged Lincoln throughout his campaign, he eventually recovered, beating Democrat George McClellan with 55% of the popular vote.

The miscegenation pamphlet was perhaps American history’s most successful fake news campaign. Long after the election, the pamphlet’s authors were revealed to be Democratic newspapermen bent on scuttling Lincoln by fanning racial anxiety among working-class white Republicans. The two writers set the controversy alight by soliciting feedback from some of the more guileless anti-slavery intellectuals, including Lucretia Mott, who voiced vague support for the pamphlet’s principals—and then sending those letters to Rep. Cox. Other Democrats had written the later batch of fake miscegenation pamphlets making the rounds in working-class white neighborhoods. Though abolitionists like William Lloyd Garrison were well aware of what was going on, they were powerless to stop it.

The miscegenation hoax wasn’t exactly an isolated incident, says Richardson. In 1860, an anti-slavery zealot named John Brown led a bumbled raid on an arsenal in Harper’s Ferry (in what is now West Virginia). Deliberately misleading reports of the incident stoked southern fears of axe-wielding abolitionists and slave insurrections, pushing the country closer to civil war. In the 1870s, a smear campaign linking president Ulysses S. Grant with corruption stymied his efforts at Reconstruction.

The parallels to today are easy to see. Back then, telegraphs and other technological changes let news spread swiftly and gave rise to more starkly partisan newspapers. Public trust in government was in tatters. With little consensus or authority over the truth, the purest gauge of veracity was gut feeling. And in an America so deeply divided—especially over differences about race—what tended to feel real were stories that confirmed fears and biases.

Curiously, the miscegenation hoax’s mark on society lingers still today. Up until 1864, the word used to described the mixing of any groups—not just races—was “amalgamation.” Combining Latin words to yield “blending” and “race,” the anonymous pamphleteers coined the word “miscegenation,” a term that specifically covered interracial unions selected to sound more “scientific.” Thus the American English lexicon had a new word—and a new notion of racial purity to panic about.