How to make the perfect mashed potatoes, according to science

As food writer Jeffrey Steingarten says in The Man Who Ate Everything, “the potato is the most important vegetable in the world.” Over 10 billion bushels of potatoes are grown every year, and you can live for 167 days eating just potatoes, Steingarten says (you’d have to eat about 3 3/4 pounds per day). Add milk to your diet and then potatoes could keep you alive indefinitely. And most Americans get more vitamin C from potatoes than they do from citrus fruits. Potatoes are a real superfood.

As food writer Jeffrey Steingarten says in The Man Who Ate Everything, “the potato is the most important vegetable in the world.” Over 10 billion bushels of potatoes are grown every year, and you can live for 167 days eating just potatoes, Steingarten says (you’d have to eat about 3 3/4 pounds per day). Add milk to your diet and then potatoes could keep you alive indefinitely. And most Americans get more vitamin C from potatoes than they do from citrus fruits. Potatoes are a real superfood.

There are many ways to make potatoes: fries, gratin, hash browns, baked, and, of course, mashed. Mashed potatoes are a staple of most classic sit-down family dinners in the US, but the cooking style can be very contentious. The basics are easy: boil potatoes, mash, add butter or cream, and voilà! But it’s not actually that simple, because potatoes have lots of starch, and starch is hard to control.

As J. Kenji López-Alt explains in his book The Food Lab, during soaking and cooking, the cells of the potato break down, releasing starch. The amount of starch released determines the ultimate texture and consistency of your mashed potatoes. If you want them creamy, you need to get enough starch out of the cells to create some texture, but not so much that your potatoes become gluey (gluey = all the starch). If you want fluffy potatoes, you need to keep the starch to a minimum possible because it weighs them down.

So how do you make the perfect mashed potatoes? You begin with the end in mind. Start by choosing a style. Then, as López-Alt says, there are three things that affect your end result: potato variety, mashing method, and soaking/rinsing.

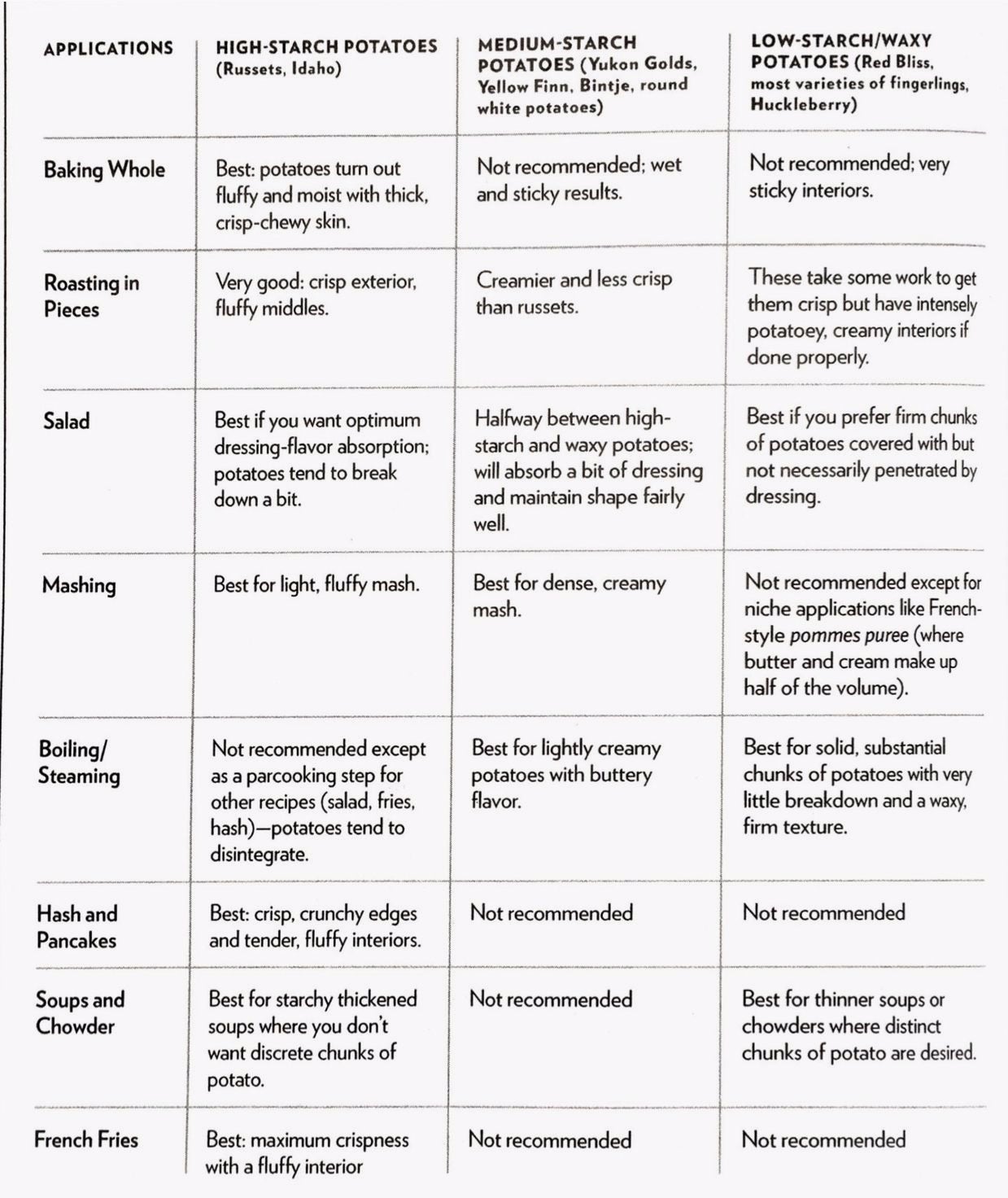

Potato varieties can be broken down into three categories: high-starch, medium-starch, and low-starch (also known as waxy). The classic russet potato has a high-starch content but is soft and easy to mash. Since they don’t require much work to break down, less starch is released in the process and the potatoes stay light. Yukon Gold potatoes are in the medium-starch category, which means they require more work and release more starch along the way.

This leads to mashing method. The more processing the potatoes go through, the more starch is released. Pressing the potatoes through a ricer, tamis, or food mill releases a minimal amount of starch. Running the potatoes through a food processor is the best way to release all the starch the potato has to give. Using an electric mixer to whip the potatoes releases some starch, but not too much.

Last, but equally important, is the soaking and rinsing process. Water literally washes off starch, but it can also wash off enzymes that break down pectin (the natural glue that holds cells together). Soaking the potatoes for too long, or cutting them too small before boiling will remove all the enzymes, leaving too much glue that can’t be broken down. If that happens, the potatoes will never become soft, no matter how long you boil them.

Before you even reach the point of throwing them into boiling water, your potatoes will have changed chemically. Controlling these processes as much as possible will drastically change the dish you make.

You probably don’t have the time (or inclination) to test out all the possible permutations of these three factors, but luckily, López-Alt already did it for you. He’s created a cooking method for both fluffy and creamy potatoes (he prefers creamy, but his sister prefers fluffy) based on the many tests he ran to find the perfect combination.