Facebook needs to hand over its algorithm if it really wants to end fake news

On Sept. 5, 2006, Facebook transformed from a technology platform into a media company. That was the day the social media site replaced its chronological list of friends’ updates with its algorithmic news feed.

On Sept. 5, 2006, Facebook transformed from a technology platform into a media company. That was the day the social media site replaced its chronological list of friends’ updates with its algorithmic news feed.

Since then, Facebook has decided everything its users—now totaling 1.8 billion on a monthly basis—see in their unique feeds. ”Once [Facebook] got into the business of curating the newsfeed rather than simply treating it as a timeline, they put themselves in the position of mediating what people are going to see. They became a gatekeeper and a guide,” wrote Tim O’Reilly, a Silicon Valley investor and publisher, in a Medium post. “It’s their job. So they’d better make a priority of being good at it.”

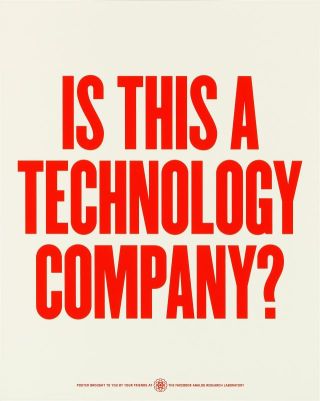

Facebook now stands as the world’s most influential editor, and perhaps its most reluctant. Its CEO, Mark Zuckerberg, has repeatedly denied Facebook is more than a technology company. The company’s main role, he argued in a Nov. 12 Facebook post, is “helping people stay connected with friends and family,” not sharing news or media. He defined the company as one that builds software and maintains servers, and only incidentally manages billions of peoples’ content. ”We are a technology company because the main thing we do across many products is engineer and build technology to enable all these things,” he wrote.

This is certainly a message investors like to hear. Being an endlessly scalable platform is much more preferable to the messy business of media. And as a blameless technology company, Facebook can float above any responsibility for content shared on its network. Its sole job is to maximize users’ “engagement” for the purpose of generating advertising revenue. But as a company making conscious editorial decisions, Facebook would risk its bottom line by favoring things such as decency, accuracy, and other considerations that may depress engagement.

This contradiction was in high relief during the US presidential election. A global cottage industry sprung up to feed fake news to Trump supporters who proved the most profitable targets for bogus information. BuzzFeed reports 17 of the 20 top-performing false election stories on Facebook were pro-Donald Trump or anti-Hillary Clinton. In the last month of presidential campaign, the number of shares, reactions and comments to fake news significantly outpaced that of mainstream reporting.

Facebook was—and remains—a very active editor in all this. Each day, the company’s algorithms weighs clicks and likes to decide what appears in users’ News Feeds. Thousands of people contracted by Facebook delete banned content such as graphic violence. Content predicted to “engage” people is heavily prioritized, while the rest sinks from view.

This process reveals a fundamental truth about being an editor, as noted by Brian Phillips at MTV: it’s not an intention, it’s something you do. And doing little or nothing to curb misleading or fake news is still an editorial decision, says Sarah Roberts, an information studies professor at UCLA. “Letting bogus news flow through their pipes is actually an editorial decision,” said Robert in an interview. “No action is not neutral.”

Time to open up

For Facebook to avoid this unwanted position, it may need to stop playing the only editor. Opinion in Silicon Valley is drifting in that direction. Paul Graham, co-founder of the Y Combinator startup fund, suggested independent parties gain access to the News Feed to help inform how information is prioritized.

The News Feed algorithm is largely a mystery to outsiders, but Facebook product managers told Quartz it relies heavily on users’ preferences—shares, likes and reports—to serve up content that will excite (or incite) friends and connections. Facebook uses ”community feedback” to avoid prioritizing misleading stories, but engagement is the overriding priority. News stories appear alongside memes, hoaxes, and conspiracy theories in a stream of information whether it comes from Fox News, Washington Post, or a freshly minted WordPress site. As people engage with content they want to hear, and share with their friends, the flywheel of fake news gathers speed.

That wasn’t a big deal when Facebook was one of dozens of social networks. Rules that applied when Facebook had 100 million users have broken down down as it approaches 2 billion. Facebook’s reach now exceeds every other player in the media industry, giving it unprecedented power over the distribution of information. Researchers have found that even even small tweaks in presenting information online can sway voter preferences. A 2014 study in the journal Science reordered Google’s search rankings by placing one candidate above another. The researchers shifted voter preferences equivalent to a 2% change in the electorate (or 2.6 million votes) in a hypothetical US election. A similar effect is possible on Facebook and other social media. Clinton, it’s worth noting, lost three crucial swing states in the Rust Belt by a combined 107,000 votes or so.

Facebook’s only chance to escape this kind of responsibility may be to open its News Feed to others, says Jonathan Zittrain, a computer science and law professor at Harvard University. “The key is to have the companies actually be the ‘platforms’ they claim they are,” he wrote on Twitter. “Facebook should allow anyone to write an algorithm to populate someone’s feed.” Giving up absolute control over the news feed would relieve Facebook of its monopoly over users’ content, as well as the company’s responsibility to manage it exclusively.

Zittrain suggested third-parties build on top of the existing algorithm, offering the News Feed as a customizable stream that others modify to suit their audiences. By allowing anyone to help populate someone’s feed, Facebook’s audience will have a choice, and transparency, into how their news is sourced, much as they do today when choosing a media source. The most egregious clickbait and hoaxes can be eliminated by repurposing existing spam and malware tools, while the hardest problem of “fake news”—biased or misleading stories from popular sites—is better left to third-parties rather than a single Facebook feed, Zittrain said in an interview.

Facebook would serve as a sort of app store for groups like the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Ralph Nader, the Republican National Committee or The New York Times to build ”feed rankers” that weight news surfaced in users’ feeds. Users could select combinations that suit their tastes. While this does not solve the filter bubble problem (people self-selecting groups they already agree with), he admits, it avoids making Facebook, along with Twitter and Google, the arbiters of what’s true or not. “That’s way too big a burden to put on one company, and it strikes me as dangerous,” he said.

Others are hoping that third-parties can label content with independent credibility rankings in the News Feed for the public or platforms to use as they choose. One approach developed by Aviv Ovadya, an MIT-trained software engineer in San Francisco, is a non-partisan, fact-based database for news. “There needs to be a third-party organization doing impartial credibility rating,” said Ovadya in an interview. The non-profit database company will collect a long-term analysis of news sources. Machine learning and crowdsourced fact checking can categorize content and verify falsifiable claims. Social media companies who want to use this data source can label news with a creditability ranking rather than screen it out entirely.

Change is inevitable

So far, Zuckerberg has shown little willingness to let others into Facebook’s inner sanctum. Academics and other research have been rebuffed from studying the company’s full data sets. Facebook is spending some of its $23 billion cash pile to buy up independent companies such as CrowdTangle that can offer insights into how content performs on Facebook. The company has also not given much time to rethinking its approach to news, reports Zittrain who has had multiple conversations with Facebook employees. “I think it’s something they care about a lot, but it’s also one of the thing where the important and urgent diverge,” he said.

But it appears handing over control to outsiders isn’t a complete nonstarter. The New York Times reported on Nov. 22 (paywall) that the social network is testing software to suppress news feed content in specific regions of China. The feature appears to be a requirement for Facebook’s entrance into the Chinese market, where it is now blocked. Rather than censor posts itself, Facebook could reportedly let third parties (most likely Chinese companies) monitor and restrict access to popular stories.

No matter what the outcome, changes will happen anyway, predicted UCLA’s Roberts. “There is going to be big shakeup,” she says. Facebook’s position is untenable. The idealistic idea, rooted in the early days of the internet, that online conversation could happen without moderation from the network designers has always been “nonsense,” she says. “We are stuck in a paradigm that is out of date, may never have been true, and does not scale.”

Public outcry is already pushing Facebook to act. The company banned fake news sites from accessing its ad network on Nov 14. Although that doesn’t affect the News Feed, Facebook has said “we take misinformation on Facebook very seriously,” in a Nov. 10 statement. “We understand there’s so much more we need to do.”

Facebook may be facing its own version of Google’s fight against “content farms” in 2011. At the time, Google was battling a rash of sites that paid writers to churn out low-quality, often inaccurate content threatening to erode trust in Google’s search results. Matt Cutts, Google head of search spam, says Facebook’s struggle mirror those of Google’s at the time. ”When external commentary started to mirror our own internal discussions and concerns, that was a real wake up call,” Cutts wrote recently on Medium. “I see a pretty direct analogy between the Panda algorithm and what Facebook is going through now.”

How did Google respond? The Panda update. It identified low-quality pages and dropped them lower in the rankings, a change estimated to affect 12% of US search queries. The new algorithm shaved off enough revenue that it had to be disclosed in later earnings calls, but it restored quality and confidence in the company’s search results, Cutts writes: ”It was the right decision to launch Panda, both for the long-term trust of our users and for a better ecosystem for publishers.”

Facebook has a harder problem. It can start by following Google’s lead by suppressing clickbait and “low-quality” results. That was ultimately a solvable problem for the search giant. Prioritizing accuracy in the content, and not just engagement, will take more—and likely some outside assistance.