From communism to capitalism: How Christmas gift-giving has changed in Poland

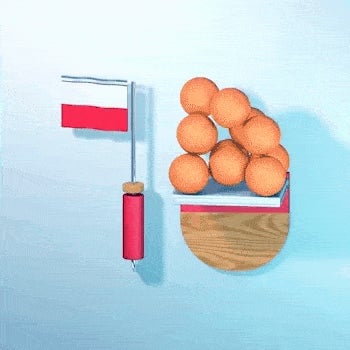

Poles who grew up during the communist era love to tell their children and grandchildren that as kids, they would be satisfied with a simple orange under the Christmas tree.

Poles who grew up during the communist era love to tell their children and grandchildren that as kids, they would be satisfied with a simple orange under the Christmas tree.

This is, in part, an admonition against expecting a bountiful haul of presents, but it’s also an expression of nostalgia for less complicated times. During the four decades of communist rule, receiving a piece of fruit was often a joyful event: “That was happiness!” my great aunt Magdalena told me.

Christmas in Poland has been an unshakable constant: a family gathering is a given, a feast will somehow be procured. The country was and is staunchly Catholic, more like a Latin American nation in its devoutness than any other European state. Communist rule did not dampen the people’s religiosity. Even the communist authorities knew that they had to provide the people with Christmas fish and meat—and if they didn’t, the people let their wrath be known. In 1970, after the authorities raised the prices of meat, ordinary Poles rebelled, leading to the ouster of a long-time communist leader.

Since the scarce times of the communist era, Christmas in Poland has changed. If you look back several decades, Christmas gifts offer a glimpse into Poland’s economic situation and political climate. In hard times, the Christmas tree gift pile might only yield a piece of candy or fruit, or a handmade hat. When communism was coming to an end in the late ‘80s, some families could afford Barbies or LEGOs, which were made available in special stores. Today, expensive presents, gift cards, or experiences (like a spa weekend) reflect Poland’s economic progress, its post-Soviet success story.

Christmas in the rubble

Poland was completely destroyed during World War II, ravaged by Nazi Germany and Soviet Russia. But even during “the war,” as it is known in the country, parents scrambled to give their kids some illusion of a normal Christmas. “There was nothing. We were happy when we got one piece of candy… Mom sewed rag dolls and dressed them, made little doll furniture,” Magdalena, born 1939, told me.

In the years following the war, many Polish families depended on packages from the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration (UNRRA), formed to help areas liberated from the Nazi yoke. From 1945 to 1947, Poland received 2 million tons of products, mostly non-perishable military food rations, but also candy and chocolate. Parents would hide them for special occasions such as Christmas. “Paczki”—packages from abroad, either from relatives or from donations, would become a mainstay of the holidays for decades to come.

Holidays under a new regime

In the 1950s, Poles had to get used to life under an oppressive, Stalinist regime, which was atheist by definition. In fact, for several years, the country’s leaders tried to make two other holidays—December 21, a celebration of Stalin’s birthday and the New Year—more important than Christmas. The Christmas tree became the “New Year’s” tree, decorated with ornaments shaped like factories, cogwheels, cranes, and army tanks. Santa Claus (Saint Nicolas) no longer gave out gifts; instead, it was Grandfather Frost, a Soviet character who wore a Russian peasant’s outfit or a gold caftan. But the ploy didn’t work, a traditional Christmas was too important for Poles.

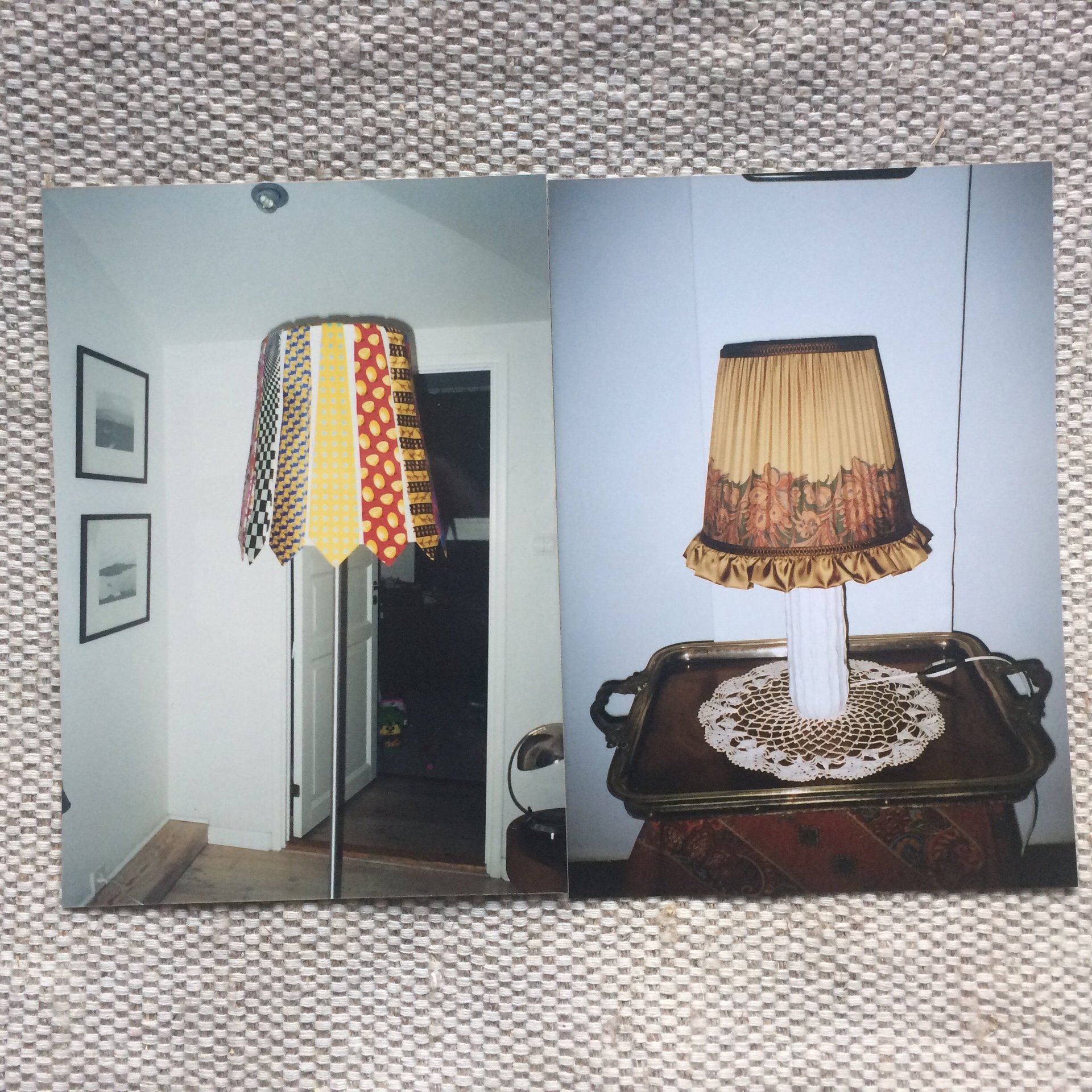

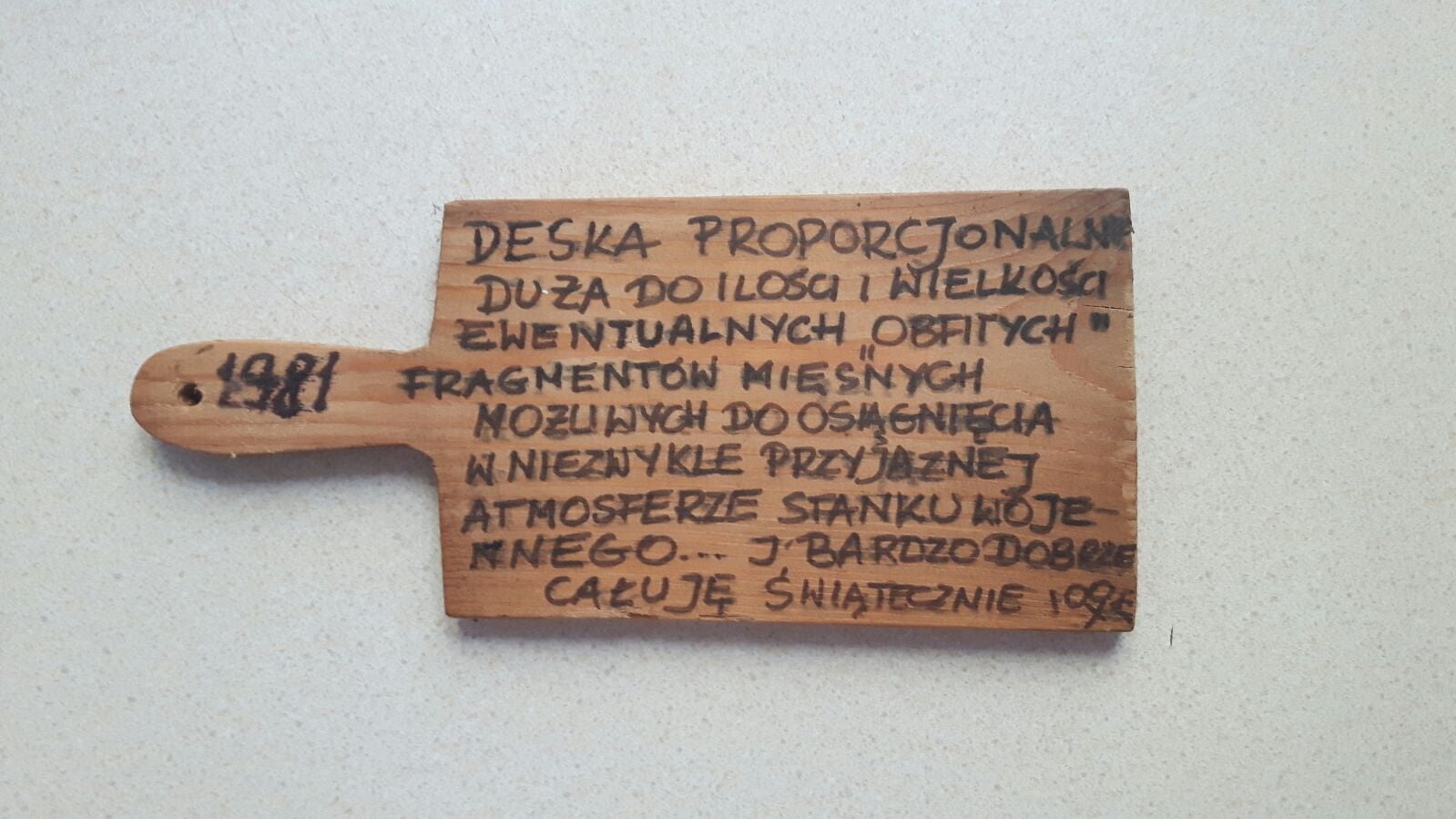

Life began to normalize in this new political reality, although store shelves remained poorly stocked. Throughout the next several decades, basic articles of clothing such as underwear and socks were considered sought-after Christmas gifts. School supplies (“a simple, pretty notebook,” Magdalena said) or used clothing from foreign donations were common presents. Another relative remembered the annual flannel shirt a seamstress aunt would make her. All throughout the communist era, handmade gifts reigned: women would knit hats, scarves, and socks; my mom and her friends would decorate cutting boards as teenagers in the 1980s and hand them out to family.

The important political lessons of Christmas

Every year, starting in the 1950s, newspapers and TV broadcasts would report how far ships from “friendly” countries like Cuba or Colombia carrying bananas, oranges, almonds were from Poland. Efforts to unload the ships were described by propaganda news reports in great detail, ensuring the people that if the army helped, the oranges would not rot before they got to their homes. In 1979, one newspaper interviewed the man who coordinated unloading the ships: “On Sunday, we took advantage of the nice weather… to unload four ships with oranges, lemons, grapefruits, and bananas. The 0°C temperature allows us to transport these delicate products to warehouses.”

“These reports would calm spirits, show that the authorities cared about the people,” said historian Marcin Zaremba.

In 1972, according to the Polish edition of Newsweek, Polish stores got an injection of products from the West: Italy, Austria, West Germany, and Great Britain. During Christmas, Polish newspapers would meticulously report what products would be available. A magazine in 1972 wrote: “Along with food products, there will be fabrics for evening gowns, exquisite women’s accessories, and gold jewelry from Lebanon.”

Even if the economy was looking better, few were able to afford these luxuries. In 1973, a state polling agency said that only about half of adult Poles received a gift for Christmas. The most popular gifts were hats, scarves, and slippers, followed by more expensive clothing such as shoes and sweaters.

A brief lapse in institutional memory had great consequences for the regime. In December 1970, the communist party leadership decided to increase the government-set prices of meat and some other grocery products. Meat on Christmas day was mandatory for most Polish families. Poles, tired of the oppression and their impoverishment rose up in protest. Massive worker demonstrations were brutally quashed by the military and police. As a result, Władysław Gomułka, the leader of the party at the time, was ousted from power. No one would repeat the mistake of making Christmas more expensive.

Five-hour lines for carp and LEGOs for the chosen few

To get anything in communist Poland, including basic foods and household items, you would have to stand in a long line—during Christmas, particularly long. And the worse the economy got, the longer the lines would become. In the mid-1970s, when the country was supposed to start paying off its foreign debt, the economic situation rapidly changed for the worse. While in 1971 the average Pole spent 73 minutes in line every day, in 1976 it was 94 minutes, according to Newsweek. Zaremba remembered a Christmas toward the end of the decade when he had to wait in line for five hours to get holiday carp.

One newspaper wrote in 1980, “There are more window-shoppers than actual shoppers.” In toy stores or clothing stores “buying something genuinely pretty, and at the same time not-too-expensive is a feat.”

Starting in the mid-’70s, it was increasingly easier to get products from the West—especially if you were relatively well-off. “Everything that ‘smelled’ of the West could be a gift—a soap, shampoo, chocolate,” my mom’s friend Dorota told me. Special stores called “Pewex” were created where you could get Western products for dollars. A VCR cost $499 in 1988—the equivalent of two annual salaries for the average Pole, according to historian Piotr Osęka.

“Pewex was a better world viewed from outside the store display. You could observe a piece of the West while never leaving Poland,” Osęka said. LEGO bricks and Barbie dolls became available for the more privileged—and this cohort was growing. In the 1980s, a form of middle-class was starting to emerge, with the authorities allowing some types of private enterprise to function. Others who had access to dollars: anti-communist opposition members, who were supported by Western money; rural families who had relatives in the US or Germany; and artists, who were allowed to travel.

Christmas in the mall, like everywhere else

The situation in Polish stores—and, by extension, under Polish Christmas trees, changed very quickly after communism fell in June 1989. The Christmas of 1990, a year after the first market reforms were introduced, was a new reality, Osęka said. Lines disappeared, shelves were stocked with products. You could get almost anything, if you paid the right price. More Poles started buying sports equipment, electronics. In a couple of years, everything was available, and Christmas quickly became fairly commercialized. The currency changed—from relationships to hard cash. Where once you needed a vast social network to get what you wanted, favor for favor, barter-style, now you needed money.

Today, thanks to the country’s largely successful economic transition, gifts in Poland resemble those in developed economies. According to research by TNS OBOP, Poles spend more on Christmas presents with every year. While more and more people shop online, malls fill up with people in the days leading up to Christmas. Christmas marketing starts in November, the earlier the better. (In the communist era, authorities would calculate how to stock stores exactly a week before Christmas in order to avoid the impression of empty shelves right before the holidays and induce a shopping panic.)

Toiletries or perfumes reign as more popular presents, but Poles are starting to gift “experiences” or “activities,” related to fitness or travel. Oranges and socks have been replaced with gift cards to a spa or for a facial. “You can also give someone a diet plan,” Dorota told me. “You never thought about this in the past because obesity was not as noticed or frowned upon.”

My mom and some of her friends make homemade alcohol or fruit preserves which they wrap in attractive packaging. Women’s magazines write about this new gift type as “fashionable,” an iteration of the organic, or “eco” food trend. “Back in the day, everyone had them at home, ate them, and didn’t celebrate them. Homemakers would make them, it was treated similarly to laundry or cleaning—no one would think to give them as a present.” An added bonus of a DIY jam or liqueur? They are a cheap gift.

My mom’s friend said that in some ways, especially for those who make less money, gift-giving during the communist era was easier: more, well, egalitarian. In a strange historical twist, with more access and more choice, money became a new problem.