The electoral college’s many flaws prove American democracy is surprisingly undemocratic

The results are still being tallied, but it is now apparent that Hillary Clinton has garnered well over two million more votes than her victorious opponent, US president-elect Donald Trump. Predictably, the outcome of this election—which is the fifth time in US history that the incoming president has lost the nationwide popular vote—has prompted calls to abolish the electoral college. It also underscores an uncomfortable paradox: America is the greatest democracy on the planet, and yet we have no true constitutional right to vote.

The results are still being tallied, but it is now apparent that Hillary Clinton has garnered well over two million more votes than her victorious opponent, US president-elect Donald Trump. Predictably, the outcome of this election—which is the fifth time in US history that the incoming president has lost the nationwide popular vote—has prompted calls to abolish the electoral college. It also underscores an uncomfortable paradox: America is the greatest democracy on the planet, and yet we have no true constitutional right to vote.

America was founded on the principle that governments “deriv[e] their just powers from the consent of the governed.” The US Constitution has been amended multiple times to fulfill this promise by expanding the franchise to adult citizens regardless of race, gender, income, or age. But the text of the Constitution also conflicts in important ways with the fundamental precept that every citizen should have a direct and equal say in how we are governed.

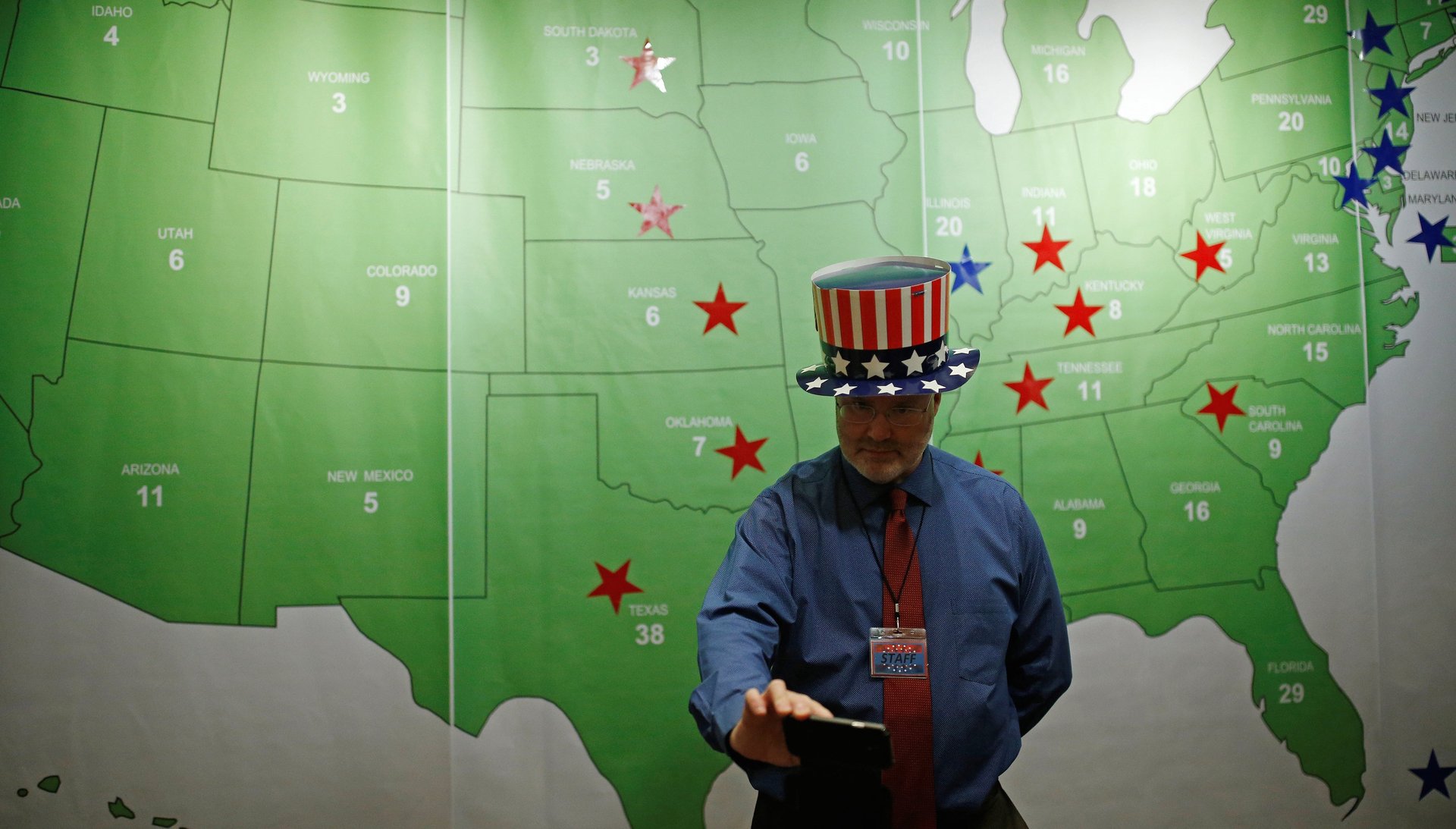

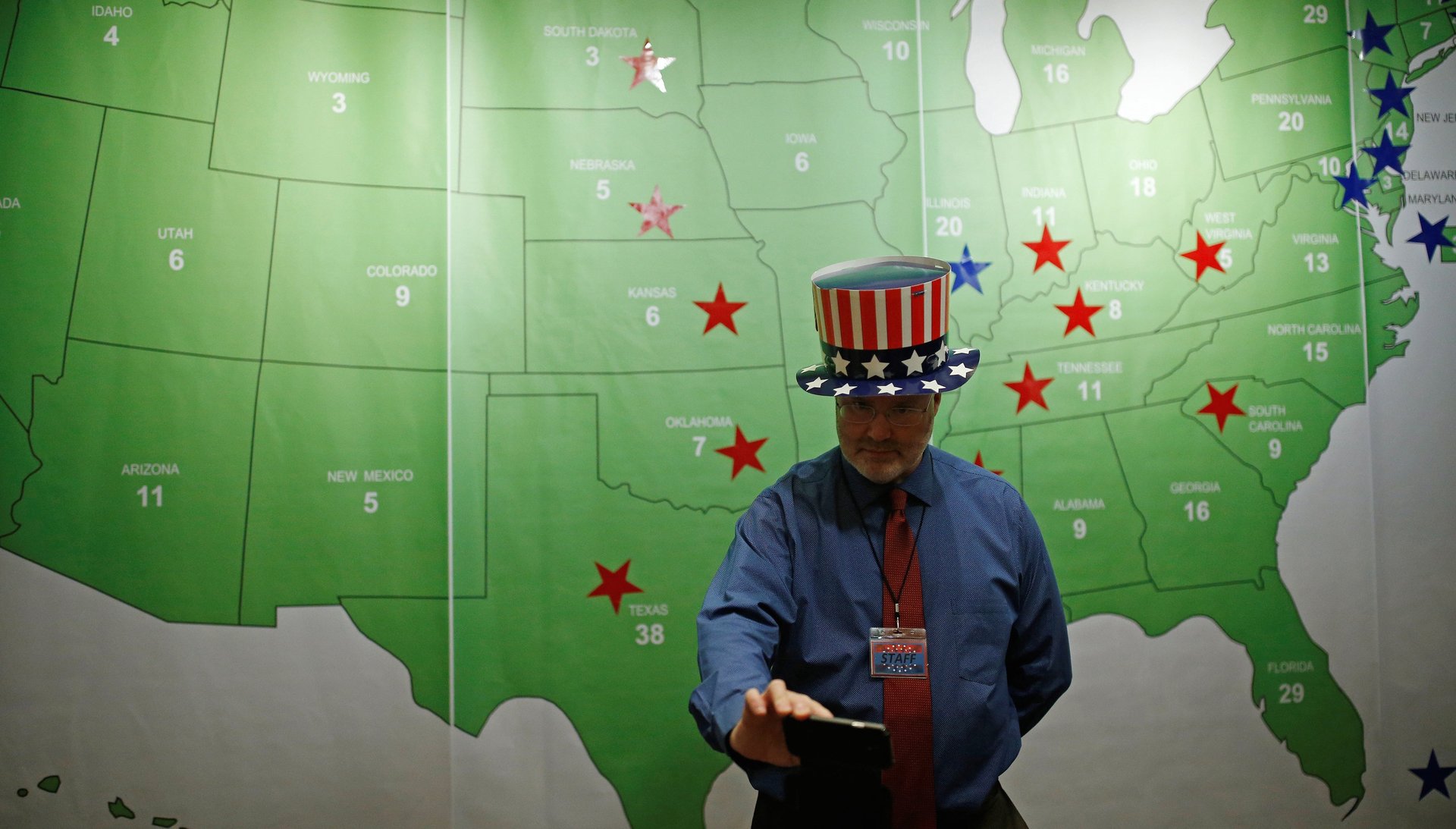

The electoral college is the clearest example of this conflict, and not simply because it permits the historical anomaly of a president who is rejected by a plurality of voters. In a country populated by approximately 320 million people, and after an election in which more than 130 million citizens cast ballots for president, the selection of our next commander-in-chief will actually be made in mid-December—by 538 people.

This is profoundly undemocratic, by design. The founding fathers originally conceived the electoral college as a buffer; the general public could express its “sense of the people” through a popular vote for electors, but the president would ultimately be selected by just a few “men most capable of analyzing the qualities adapted to the station and acting under circumstances favorable to deliberation.” You can credit Federalist and hip-hop sensation Alexander Hamilton for advancing this elitist notion.

In this day and age, of course, the electoral college now serves to ratify the results of statewide popular elections. Electors are party loyalists who usually (but not always) reflect the will of state voters, often under compulsion of state law. Yet even this safeguard is by convention and state practice, not federal constitutional guarantee. The Constitution still provides, as it did in 1788, that electors are selected in each state “in such Manner as the Legislature therefore may direct.”

In Bush v. Gore, the landmark Supreme Court decision that effectively decided the 2000 presidential election, the Supreme Court reminded us that the state power to choose electors is absolute, and a state “of course… can take back [from the voting public] the power to appoint electors.” Indeed, while that case was being decided, the Republican-controlled legislature in Florida was preparing to do just that: appoint a Republican slate of electors ready and willing to vote for George W. Bush regardless of the outcome of the court-ordered recount. That result would have offended our sensibilities and modern expectations, but not our Constitution.

The right to vote in congressional elections is more direct, but also prescribed by the peculiar and sometimes highly undemocratic design of our Federalist government. Every state has equal representation in the Senate, for example, which means that citizens of sparsely populated states like Wyoming and Vermont enjoy vastly more voting power than citizens of the largest states.

House seats, which are apportioned within each state based on population, also vary in population size due to the requirements that congressional districts not cross state lines and every state have at least one representative. States have tremendous leeway to draw congressional districts to maximize the voting power of members of the governing party; the Supreme Court has yet to strike down a gerrymandered district that was designed for partisan advantage (although it probably will have a new opportunity to do so soon).

Meanwhile, more than 650,000 residents of Washington, DC— because they live in an enclave under the exclusive control of Congress—have no right whatsoever to vote for any representation in either the Senate or the House.

In Pennsylvania, Michigan, and five other states, there is no early voting or in-person absentee voting; in Colorado, Washington, and Oregon, virtually the entire populace votes by mail. Based on the state in which you live, your right to vote depends on whether and when you registered to vote, whether you have photo identification with you at the polls, and whether you have previously committed a felony and served your sentence. Over 1.5 million ex-felons in Florida—which is more than 10% of the voting age population—could have voted for president this year if they had simply moved to Maine or Vermont.

Our democracy is more fragile than we would care to admit. The Constitution, which is 228 years old and is showing its age, was drafted in a far different and less egalitarian time. The gulf between what our Constitution guarantees and the basic democratic precepts that we have come to expect is bridged by historical practice and behavioral norms. But those norms are only as secure as the public’s commitment to police and enforce them.