An election recount will only further divide a fractured America

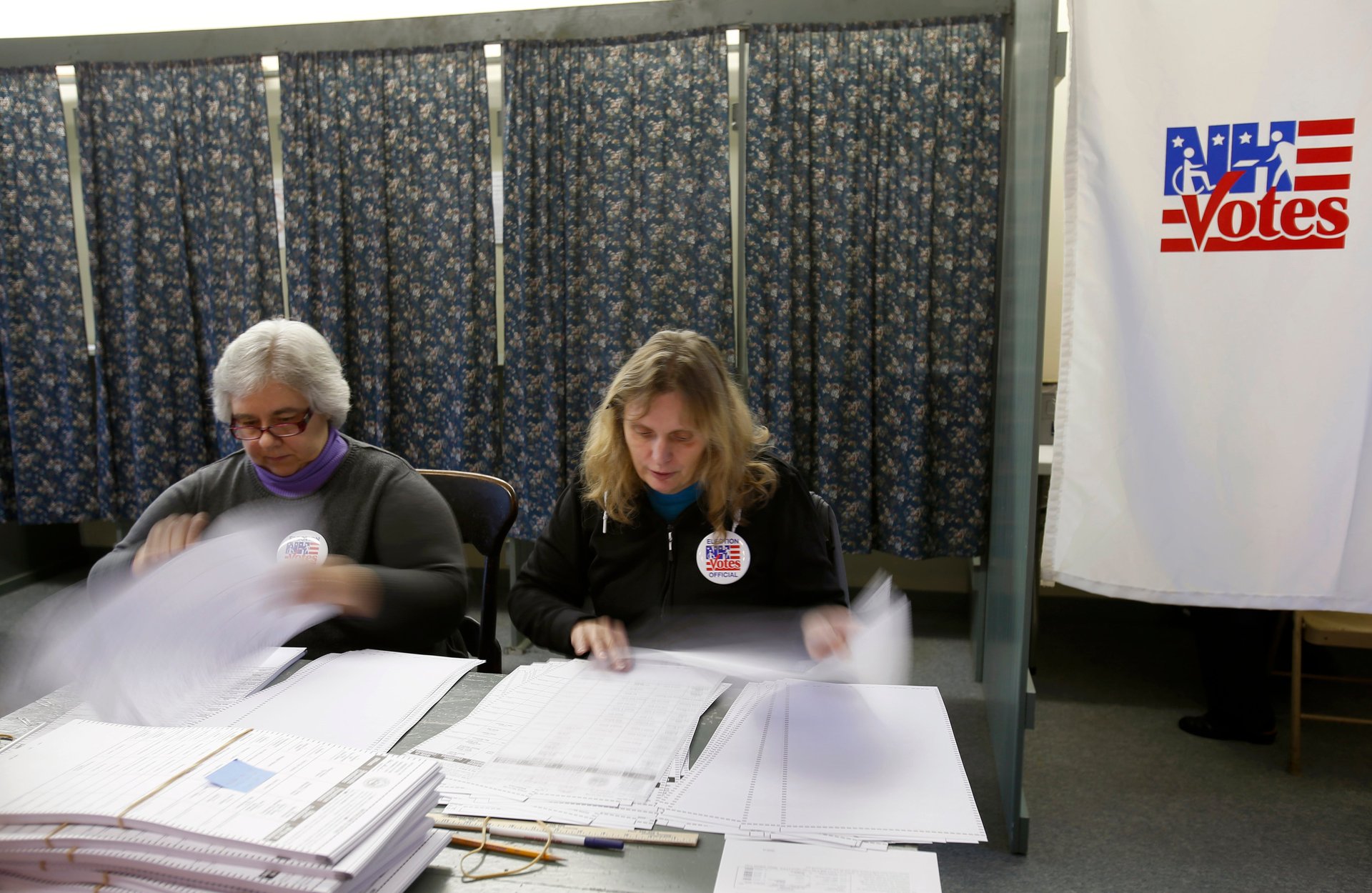

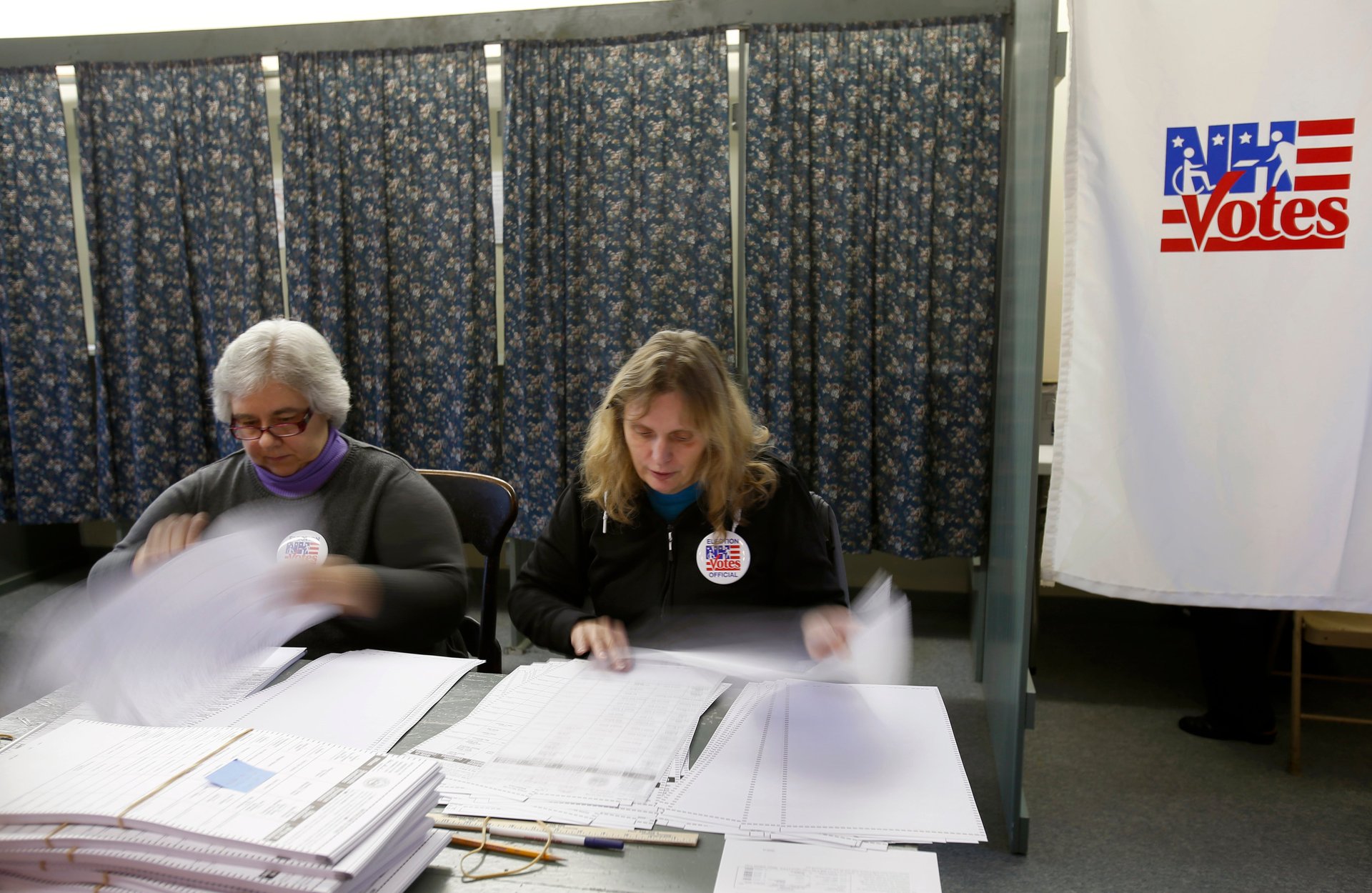

By demanding an audit and recount of the presidential election results in Wisconsin, Michigan, and Pennsylvania, Green Party nominee Jill Stein is playing into the narrative that the elections might have been manipulated and that Donald Trump might not be the legitimate president-elect. Though the Green Party has every right to demand a recount, they are playing a potentially dangerous game, considering what their options are should the recount unearth actual evidence of voter manipulation.

By demanding an audit and recount of the presidential election results in Wisconsin, Michigan, and Pennsylvania, Green Party nominee Jill Stein is playing into the narrative that the elections might have been manipulated and that Donald Trump might not be the legitimate president-elect. Though the Green Party has every right to demand a recount, they are playing a potentially dangerous game, considering what their options are should the recount unearth actual evidence of voter manipulation.

So far, the campaign is selling the recount more as a way to examine the fairness of the electoral process than as a late-stage effort—very late-stage—to deny Trump the White House. But of course, every whiff of irregularity would nevertheless undermine the legitimacy of the incoming president.

The Clinton campaign was also quick to rekindle suspicions of possible Russian interference in the elections, with Marc Elias, the campaign’s counsel, writing that “this election cycle was unique in the degree of foreign interference witnessed throughout the campaign: the U.S. government concluded that Russian state actors were behind the hacks of the Democratic National Committee and the personal email accounts of Hillary for America campaign officials.”

I cannot help but wonder what the response of the Clinton campaign would have been had Hillary Clinton won the election and Trump had demanded a recount two weeks after the elections had ended.

A little over a month ago, at the third presidential debate, Clinton called the prospect of Donald Trump possibly refusing to accept the results of the presidential election “horrifying.” “That is not the way our democracy works,” Clinton said at the time. “We’ve been around for 240 years. We have had free and fair elections. We’ve accepted the outcomes when we may not have liked them.”

Why would it be “horrifying?” Because as paradoxical as it may sound, the relevance of modern democracy as a political system goes beyond the fact that it is the people who are electing new rulers and law makers. The peaceful transition of power at regular, predetermined intervals is at least as important. That is what makes democracy a better safeguard against revolutions, uprisings, and civil wars than autocracy. (One only has to look at civil war-torn Syria to see the validity of this point). While they have accepted the overall result of the election, once the losing side starts questioning and stops respecting the outcome of the electoral process, its function of bulwark against political instability quickly erodes, and with potentially devastating effects.

Meanwhile, Democrats are also mounting an effort to use the electoral college for what they argue it was intended to be: a last line of defense against electing a president unfit for office.

Remembering Alexander Hamilton, who once said the electoral college exists to ensure that “the office of President will never fall to the lot of any man who is not in an eminent degree endowed with the requisite qualifications,” Democratic electors Michael Baca of Colorado and Bret Chiafalo of Washington state are trying to persuade Republican electors to vote for someone other than Trump. Chiafalo justified trying to sway electoral collage votes by arguing that “we’re trying to be that ‘break in case of emergency’ firehose that’s gotten dusty over the last 200 years. This is an emergency,” while Michael Baca insisted that “we must do all that we can to ensure that we have a reasonable Republican candidate who shares our American values.”

It all sounds very lofty, but what it comes down to is that in the eyes of Baca and Chiafalo, the decision as to who a “reasonable” Republican candidate is should apparently be left to 538 people, rather than 219 million eligible voters. In effect, what they are proposing is for the electoral college to transform the United States from a democracy into an oligarchy, not unlike Russia, China, and North Korea—not exactly the kind of political system we should envy, I should say.

But let’s suppose they succeed. Let’s suppose they are able to convince enough Republican electors to vote for a ‘reasonable’ other Republican. Or that the Green Party and Clinton campaign’s recount effort in Wisconsin, Michigan, and Pennsylvania—where, according to computer scientists, Clinton received 7% fewer votes in counties that relied on electronic-voting machines compared with counties that used optical scanners and paper ballots—turns up actual evidence of voter tampering.

What then?

Would president-elect Trump accept it? Would Republican law makers, governors, and generals who have just woken up to the fact they could benefit greatly from a Trump presidency, both politically and personally, accept it? Would Trump’s energized tens of millions of supporters, who have attached their hopes and dreams to his promise of making America great again, accept it?

No, of course they wouldn’t.

And if they don’t, how long would it be before tens of millions of Clintonians start marching through the streets, demanding the electoral college give the vote to Hillary? And if it did, how long would it be before tens of millions of Trumpists start marching through the streets, demanding Congress to refuse certifying the electoral college results? And what would be the stance of the Obama administration? Would they continue to work with Donald Trump’s transition team, or would they shut them out and start working with Clinton’s hastily reassembled transition team instead?

Before long, the Supreme Court would have to be called upon to prevent the country from falling further into political disarray, as it did back in 2000. More than any other institution, the Supreme Court is considered the nation’s last line of defense against total chaos. If only the Court itself were not hopelessly divided as well, 4-4. And then what?

The checks and balances within the Constitution can protect the people against any one branch of government becoming too powerful, but ultimately, no Constitution can protect a divided nation from falling apart. Only the people can.

The uncomfortable truth is that no one will be able to prove conclusively that the elections were not hacked on any level. But at a moment when the country is perhaps more divided than it has been in 150 years, we should focus on the peaceful transition of power, rather than continue digging for even more divisiveness.