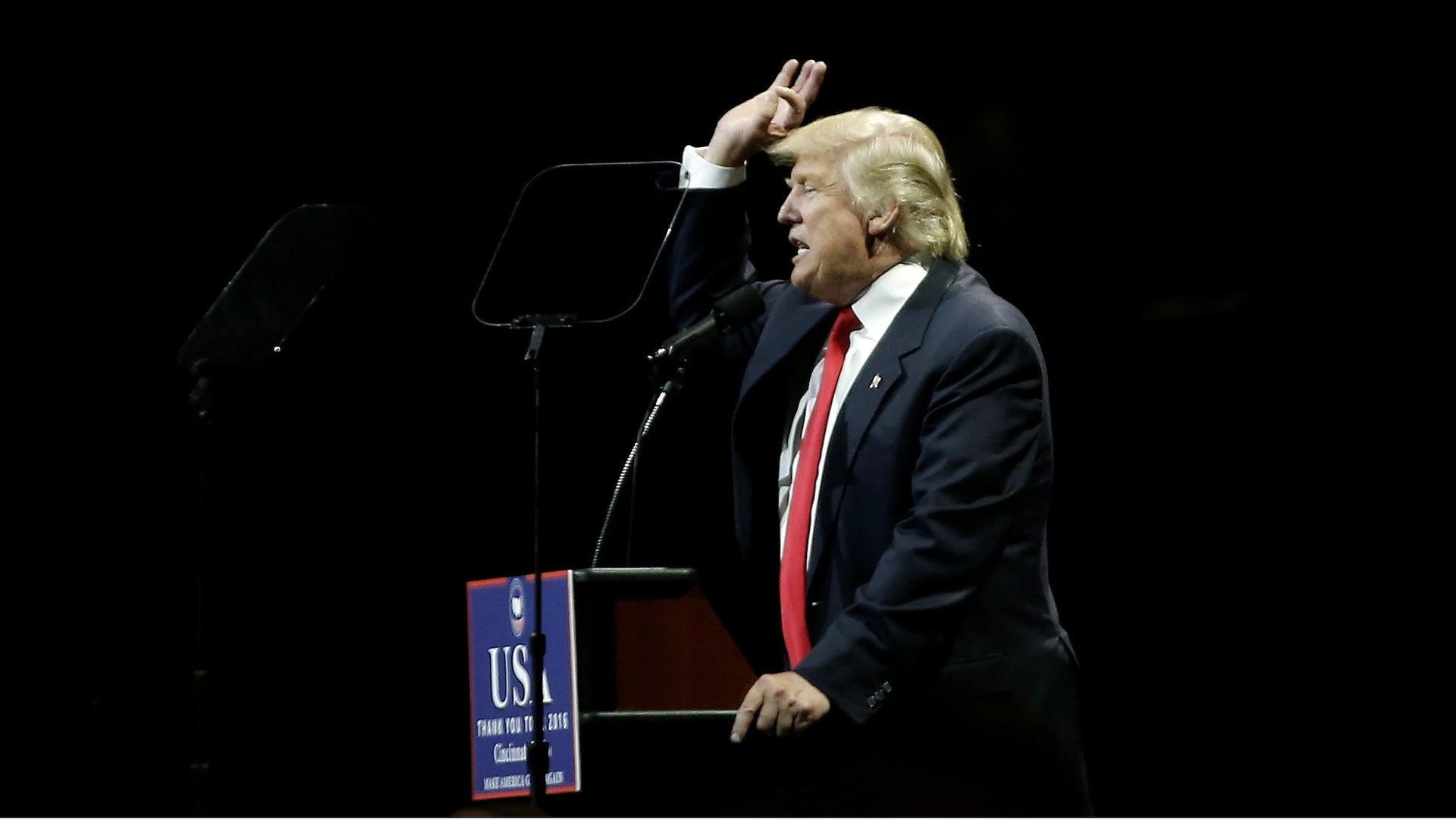

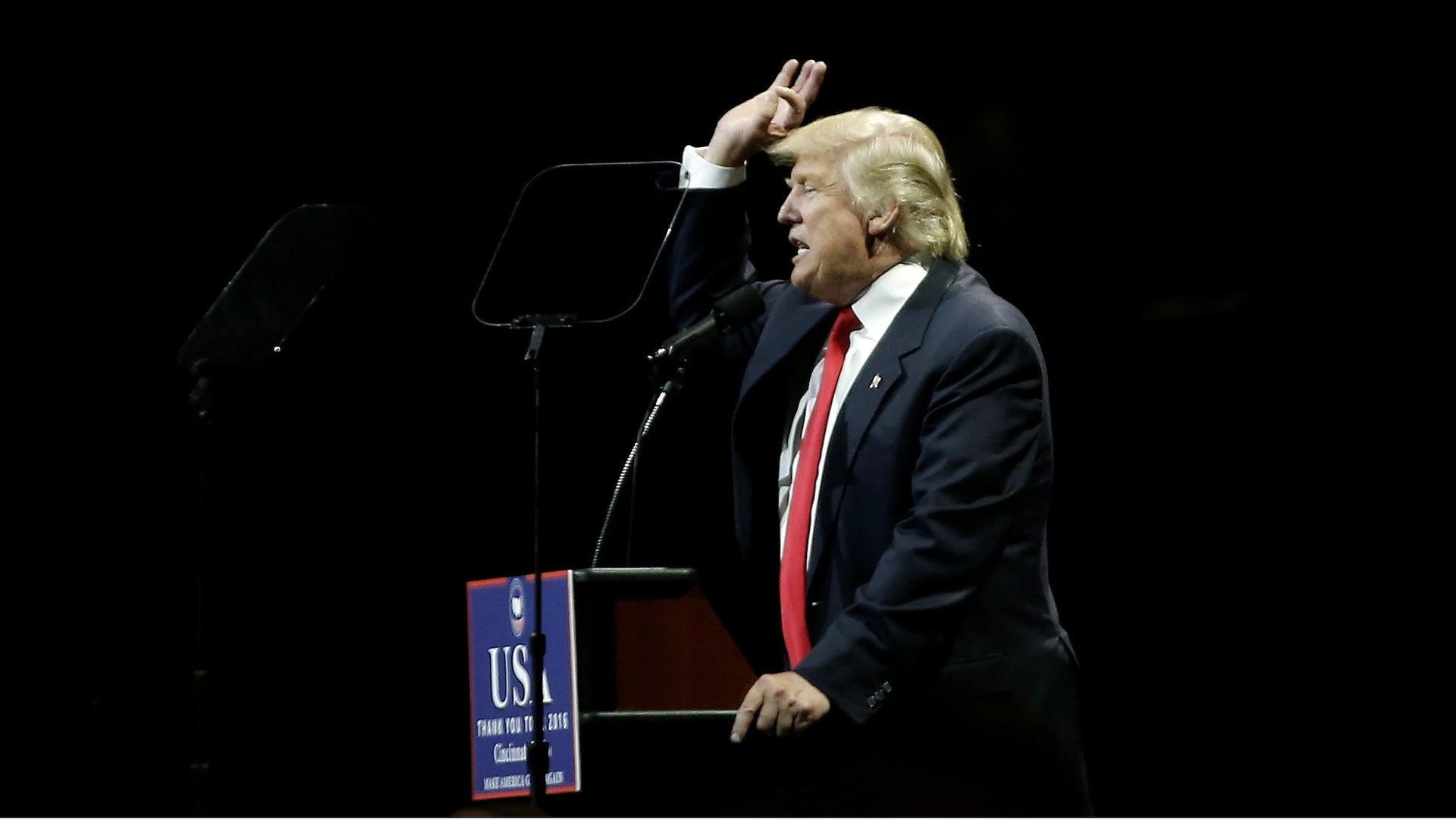

Trump’s plan to cap the mortgage interest tax deduction is great news for rich people

Populist-elect Donald Trump is boldly taking on one the most politically popular tax break on the books in an effort to revive America’s middle class. Or at least, that’s what Steve Mnuchin, Trump’s pick to head up the treasury, promised when he revealed a cap on mortgage interest deductions as part of “a big tax cut for the middle class,” in a CNBC interview on Dec. 1.

Populist-elect Donald Trump is boldly taking on one the most politically popular tax break on the books in an effort to revive America’s middle class. Or at least, that’s what Steve Mnuchin, Trump’s pick to head up the treasury, promised when he revealed a cap on mortgage interest deductions as part of “a big tax cut for the middle class,” in a CNBC interview on Dec. 1.

This indeed sounds like some American greatness-making in action given that the mortgage interest deduction overwhelmingly benefits the rich. It’s also expensive, costing the US around $96 billion in foregone taxes.

But a closer look at what Trump and Mnuchin’s plan hints that the rich don’t have too much to worry about—and everyone else does.

The deduction—which was first instituted in 1913, but shaped into its current form under Ronald Reagan’s sweeping 1986 tax overhaul—lets homeowners slash their tax bill by subtracting interest paid on their mortgages from their incomes. Realtors often tout the deduction as an incentive for prospective homeowners to buy. So popular is the deduction that proposals to fiddle with it are inevitably cut from tax reform packages (including the most recent one sponsored by Republican House speaker Paul Ryan).

Less well known, though, is that the America families actually benefit from the mortgage interest deduction—and those that do are wealthy.

Only about one-fifth of America’s 125 million households actually reap the rewards of this tax credit. This is in part because a third of families own their homes outright. But the main reason is that the vast majority of poor and middle-class homeowners neither earn enough nor have big enough mortgages debts to benefit (this post by Center for Economic and Policy Research breaks down the math). So instead of encouraging homeownership—its intended goal—the deduction invites better-off households to buy more homes, with more leverage, and at higher prices than they otherwise would, according to the Tax Policy Center. In markets where housing supply is tight—i.e. most US cities—excess demand drives up prices.

So what is Trump planning?

“Any reductions we have in upper income taxes will be offset by less deductions so that there will be no absolute tax cut for the upper class,” said Mnuchin.

The details tell a different story, though. Mnuchin said the president-elect will limit the total amount of all deductions taxpayers may take—including spending on mortgages and certain other expenses—to $100,000, according to CNBC (and they would still “allow some deductibility,” Mnuchin added).

Most people pay vastly less mortgage interest. Back of the envelope math suggests you’d have to have a mortgage of $2.2 million to hit a $100,000 cap, assuming a 4.5% mortgage interest rate. Of course, wealthier taxpayers often take other deductions as well (including one on property taxes), but clearly, a cap that high would affect only a rarefied few.

This isn’t to say Trump is totally off-track, though. Swapping out deductions for credits, as he has proposed, would create a much fairer taxation system. In general, deductions favor the wealthy since those taxpayers are on the hook to pay a higher share of their income.

But limiting them isn’t enough. The proposed deduction caps fall short of offsetting deep tax cuts on estates, business earnings, and capital gains—income that mostly accrues to the wealthiest Americans—say tax experts (paywall).