Indians are hacking into Pakistani computers with promises of defense secrets

While the Syrian Electronic Army gets all the publicity and the US-China hacking campaigns are now well known, India and Pakistan quietly have their own thing going on. According to two anti-virus firms, ESET and Symantec, Pakistani government agencies have been targeted by spear-phishing attacks—fraudulent emails that trick people into giving up sensitive information—from India for at least two and as long as four years.

While the Syrian Electronic Army gets all the publicity and the US-China hacking campaigns are now well known, India and Pakistan quietly have their own thing going on. According to two anti-virus firms, ESET and Symantec, Pakistani government agencies have been targeted by spear-phishing attacks—fraudulent emails that trick people into giving up sensitive information—from India for at least two and as long as four years.

Targets receive an email with attached Microsoft Word or pdf documents, with names like pakistandefencetoindiantopmiltrysecreat.pdf (Pakistan defense to Indian top military secret) and pakterrisiomforindian.pdf (Pak terrorism for Indian). The contents of the documents supposedly outline ”India’s ambitious defense policy” and its plans to “fight China and Pakistan at the same time.” Despite the far-fetched nature of the latter scenario, enough people opened the files, which contained malicious code that installed itself on their machines. More baffling yet, they were impressed enough to forward the files on to other hapless victims.

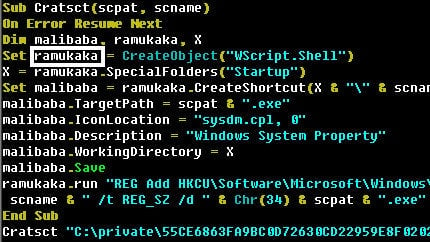

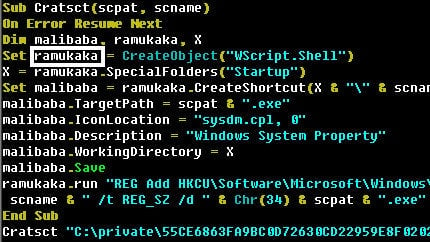

Once installed, the malware can, among other things, log the user’s keystrokes (and thus record messages or passwords), take screenshots of the infected computer’s screen, copy itself to memory sticks, and connect to a remote server from which the computer can be controlled or have more information sucked out of it. But it isn’t a particularly sophisticated attack. According to ESET, the attackers used publicly available tools, allowed the code to add an item to the computer’s system menu (meaning that an alert user would notice something suspicious) and didn’t bother encrypting communications to their server. ESET speculates that the reason for the clumsy approach may be that nothing fancier was needed.

Pakistan is not the only country attacked, though it is host to 80% of ESET’s detections. Among others countries affected are the US, Brazil, Russia and India itself. Although it is hard to prove the attacks originated in India, ESET pointed to timestamps found by its researchers that matched Indian working hours. More incriminatingly, some of the variables within the code were named after Indianisms. One was called “ramukaka”—Ramu is a nickname and kaka means uncle. Another was “malibaba”: Mali is a surname and also a common noun for gardener, while baba is a suffix generally used to address baby boys.