How the humble greeting card continues to thrive in the digital age

Every year Americans buy 6.5 billion greeting cards, according to the Greeting Cards Association (pdf). Birthdays, graduations, anniversaries: the average American purchases 34 cards a year; the average Brit buys 46 a year.

Every year Americans buy 6.5 billion greeting cards, according to the Greeting Cards Association (pdf). Birthdays, graduations, anniversaries: the average American purchases 34 cards a year; the average Brit buys 46 a year.

Cards are exchanged through the year, but nothing comes close to the winter holidays—and particularly Christmas. In the US, 1.6 billion Christmas cards are sold every year. In the UK, it’s 900 million, which doesn’t account for photo cards that people may send as season’s greetings, or handmade ones.

It’s a large market that caters to a widely held desire: to share greetings with friends and family in a personal, yet efficient, and affordable way. This need is as relevant today as it was nearly two centuries ago, when greeting cards were first introduced. Since then, they’ve become entrenched in our holiday customs and remained so, despite the fact that most of our communication has shifted to digital media.

Once upon a time in Prussia

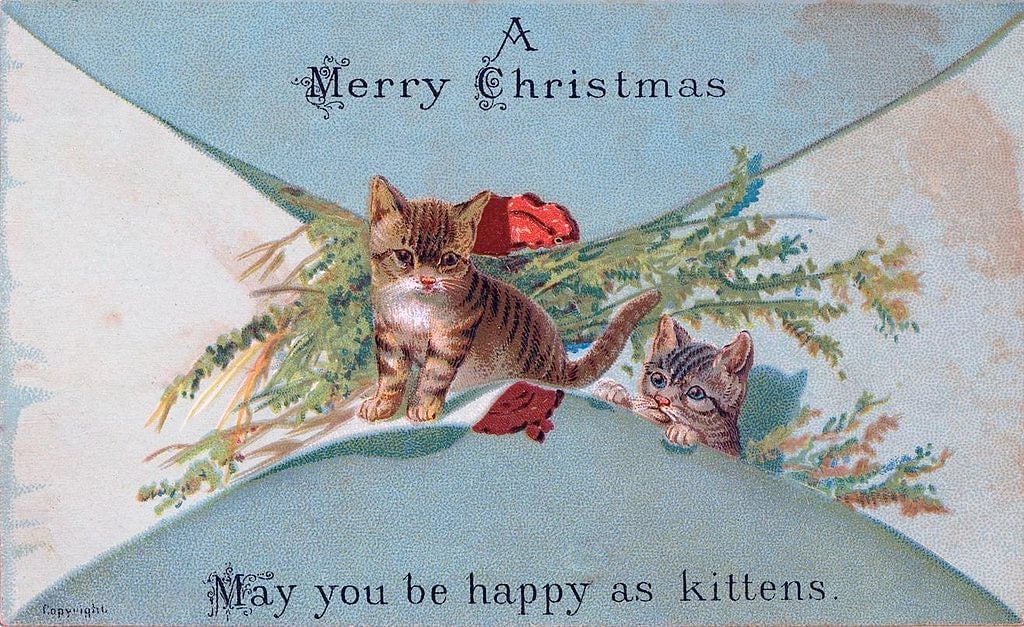

The story of how greeting cards became a staple of year-end celebrations begins in Victorian England. At the time, Christmas was celebrated by feasting and exchanging gifts.

Cards evolved from two practices that were common in the first half of the 19th century: visiting cards, which aristocrats gave hosts during a visit, and reports sent home by students, typically around the end of the year, to update their families on their studies.

The combination of these traditions gave birth to Christmas cards, which were personal (early cards were handmade), relatively inexpensive, and less time consuming than writing a letter.

Yet the exchange of Christmas cards didn’t take off until the 1840s, when Queen Victoria published an engraving showing celebrations of Christmas at Windsor. This prompted her subjects to follow her example and send out their own Christmas wishes.

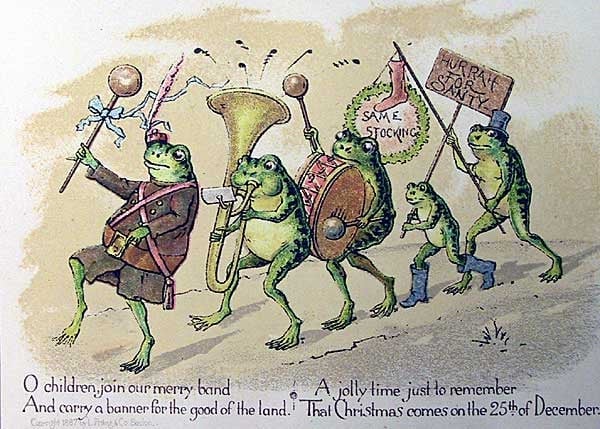

In 1843, the first Christmas card was commissioned and printed in London by civil servant and entrepreneur Sir Henry Cole, who sought to make a profit from the trend. The run of 1,000 cards, which featured a raucous group flanked by scenes of charity, were sold for a shilling each. It was not a cheap purchase, a shilling would be worth about £10 to £20 today ($12 to $24), but one that has appreciated in value: of the 12 surviving cards from the original print run, one was sold on auction in 2001 for £22,500 ($28,000).

As a result of industrialization, people had more disposable income and could afford to buy cards. But it was another measure that ultimately made the tradition of exchanging cards popular. “There was also a postal reform going on at the time: in 1840, a British act was passed called the Penny Postage Act, and that allowed anyone to send [cards] for just a single penny,” says Samantha Bradbeer, a historian at the Hallmark Archive.

This allowed people to send cards to friends and family who lived far away for a set, affordable price. Previously, the cost of postage was determined by the distance the mail would travel, and the number of sheets of paper rather than their weight.

Greeting cards remained a side business for printers for a couple of decades. By the 1870s in England, and across Europe, there were several card manufacturers printing Christmas cards.

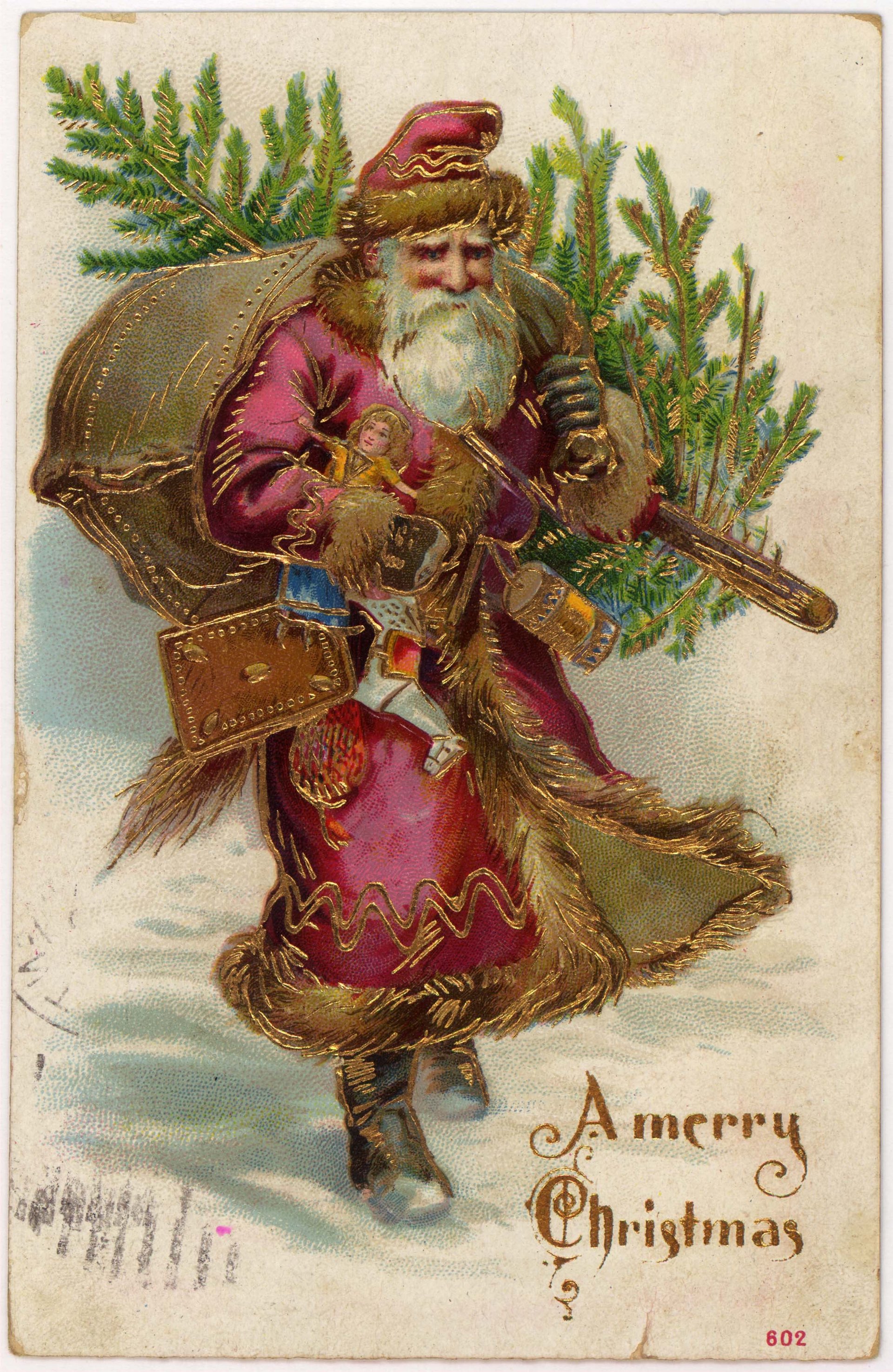

By 1875, the Christmas card made the jump across the Atlantic ocean to create the largest Christmas card tradition in the world, thanks to Louis Prang, an immigrant from what was then Prussia (now Poland). Prang, who owned a lithography business in Boston, brought to America the printing ingenuity of Germany, and printed the first Christmas card using the chromolithography technique,”to make prints look like paintings,” explains Carlos Llansó, president of the GCA and CEO of Legacy publishing group.

In 1906, in Brooklyn, Ohio, another Polish immigrant, Jacob Sapirstein, founded American Greetings, which has since grown into a greeting cards company with $1.9 billion revenue a year.

Shortly after, in 1910, Joyce Clyde Hall, a young postcard seller, founded in Kansas City what would become America’s other greeting card giant, Hallmark, a company with a revenue of $3.7 billion.

Initially, greetings were sent as postcards with the pre-written message and illustration on the front and the address on the back. Customers began adding some personal writing, and by 1915 folded cards sent in envelopes started becoming more popular. “Having an envelope allowed you to have more space to write, and add in a photograph or a small cash gift, so [the card] could be more than a form of communication. It could also be a gift,” says Bradbeer.

The glittering years

The intricate designs and decorations that are commonplace today became part of greeting cards in the 1920s; buttons and glitter adorned Christmas cards in particular. The more elaborate cards were, and still are, small presents within themselves, says Bradbeer.

While Christmas took the lion’s share of season’s greetings, card makers soon added designs to celebrate other denominational holidays: by the 1920s, there were Jewish New Year cards, by the 1940s, Hanukkah cards

In the 1950s and 1960s, the industry boomed. Cards were cheap—until the 1950s, it was possible to find some for 5 to 10 cents—and became an influential piece of American culture. Hallmark would commission its designs from the likes of Salvador Dalì, Norman Rockwell, Winston Churchill, and leading artists would make their own cards, too, some of which are now collected by the Smithsonian foundation in Washington, DC.

In 1962, the US post office introduced Christmas stamps, adding an official layer onto what was now a cultural tradition.

Tradition is the future

And then the destroyer of all things print came along—the internet.

“Sometimes you hear things like ‘with the rise of the internet sure people are sending fewer Christmas cards and millennials don’t care as much about that,'” says Darren Abbott, creative vice president at Hallmark Cards. “Actually the opposite is true,” he explains, “[younger consumers] they see greeting cards as one more tool, they kind of complement what they have on Facebook and Instagram and other forms of social media.”

Llansò, too, says the impact of digital media—e-cards, and social media—hasn’t been catastrophic, as it was once feared. “The internet, social media, they have a place,” he says, “but you can’t replace a card with that, you can’t replicate the sentiment of sending or receiving a greeting card.”

Cards continue to serve their original purpose, so well that the industry is growing in new markets such as Latin America and Asia. 2015 was the biggest year ever for greeting cards sales in the UK, with a market value of £1.7 billion (equal to about $2.5 billion in 2015—$2.1 billion as of Dec. 2016).

In the US the industry it’s an estimated 3.2% smaller in 2016 than it was in 2011, but it’s still large enough so to encourage new players to join the many thousands of greeting cards publisher (over 3,000 in the US alone). For instance, lovepop, a Boston-based startup, is focused on custom-designed 3D cards whose revenue grew tenfold in 2015, after raising $23,000 through a Kickstarter campaign.

The trend lovepop taps into is one that larger greeting card companies aren’t ignoring either: customization. According to Abbott, it’s one of the areas in which the internet has influenced, but not necessarily compromised, the greeting card industry. Through platforms like Instagram or Snapchat—the younger consumers got used to personalizing their digital identity and they value the opportunity to do so in greeting cards, too. To answer this desire, Hallmark is experimenting with customizable cards, which are being soft-launched this holiday season.

Similarly, people are using digital technology to make and enhance their greeting cards (for instance through photo cards which account for 40% of the $1.9 billion photo merchandise market), not to replace them.

Plus, Llansò says, the story of Christmas cards isn’t necessarily one of innovation. In fact, a great deal of the popularity of the gesture has to do with its traditional value. It’s not a coincidence that the most popular Christmas card of all time is Three Little Angels, which was designed by Ruth Morehead for Hallmark in 1977, and inspired by her and her two sisters. The card, reading “God bless you, love you, keep you at Christmastime and always” sold 37 million copies by 1996, and has sold millions more since.

While it has evolved to offer with angels of different ethnicities—the core design has remained the same for four decades and is, to date, a best seller.