I sent the first email between heads of state—but the real revolution of connectivity is still to come

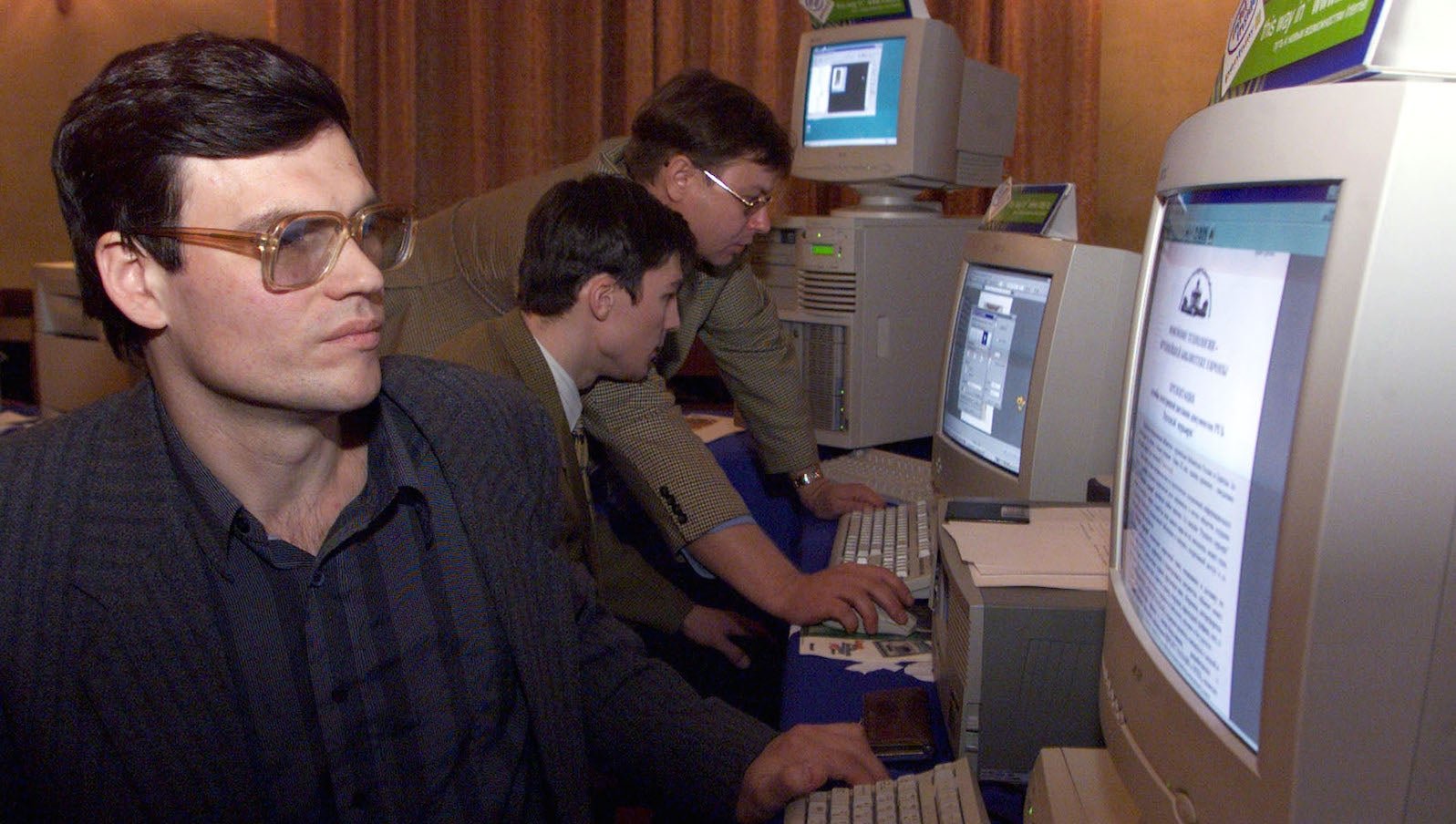

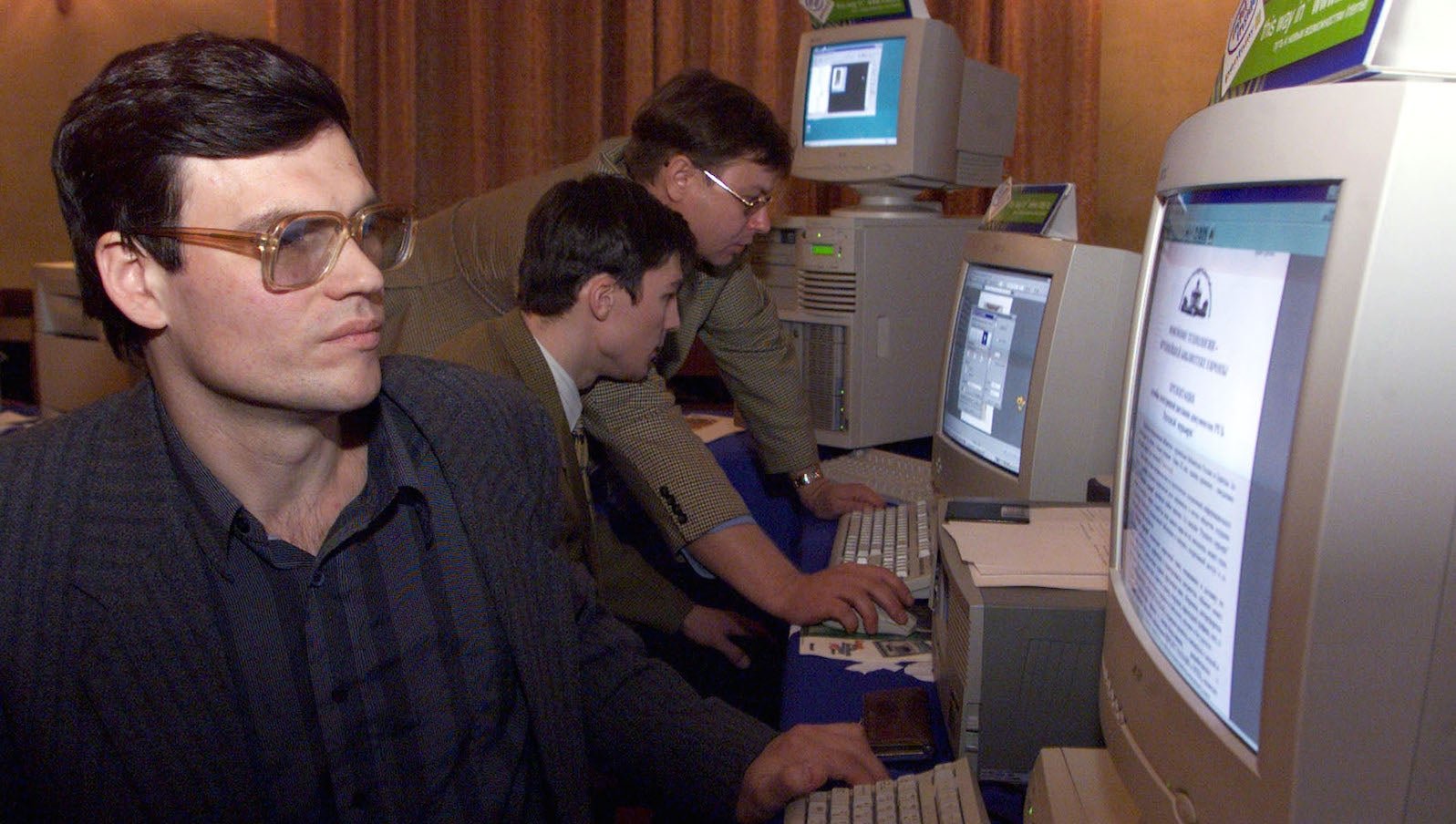

In 1994, when I was prime minister of Sweden, I sent the first email between two heads of state.

In 1994, when I was prime minister of Sweden, I sent the first email between two heads of state.

I had been discussing with Al Gore the development of what people at the time called, “The Internet Superhighway.” So I thought it would be a good idea to send an email to then-US president Bill Clinton. There weren’t many connection hubs in Sweden, but we found one in Stockholm. I managed to send Clinton an email to congratulate him on ending the trade embargo with Vietnam—the first digital message between two heads of state.

We waited for a reply, but we didn’t hear back. After several days, one of my staff members called the White House to ask if they had received it. It turned out that they hadn’t connected their system yet!

At that time, email was seen as revolutionary; 1994 was also the year the first commercial web browser appeared.

Technology can be an enabler, but it can also create divisions. The primary division I see is generational. Young people around the globe are making new virtual connections with each other using new systems, apps, and structures. Meanwhile, many of their parents barely understand what their children are doing.

We need to have an inclusive global digital economy, but half of the world’s population remains offline. Politicians and policy-makers need to encourage free internet access in order to help as many people as possible get connected.

The good news is that internet access will increase quickly once it depends less on physical infrastructure and more on digital infrastructure. Within five to six years, I predict 90% of the world will be covered with mobile broadband networks of the same or better quality than we have in most of Europe today. But we need to make it affordable as well. This will require a benevolent regulatory environment and healthy competition—the opposite of the monopolizing, old-style telecoms structures that thrive in corrupt regimes.

Sweden is a clear example of the way competition can drive prices down. We implemented a fairly radical deregulation and privatization program across the telecoms sector in the early 1990s, and we now have one of the best internet frameworks in the world.

On the other hand, one of the most extreme examples of cheap connectivity is Somalia, which has virtually no regulation and has some of the lowest prices for mobile communications in Africa. Quite a number of operators and private entrepreneurs have been going into Somalia and setting up networks. Since people need to communicate—even in difficult situations—the demand has been great, making connectivity cheap.

Another example of a country that has been very successful, perhaps surprisingly, is Afghanistan. Fifteen to 20 years ago it had virtually no connectivity whatsoever. Today it has reliable and widespread mobile communications which facilitate economic, political, and social development in a profound way. This is largely thanks to Afghanistan’s broad connectivity infrastructure.

The next generation of workers will live in a truly digital society, and many sectors will be forced to adapt accordingly. One example of a sector that has already been transformed is the music industry. Once upon a time we had vinyl records, then we moved to CDs, and now music lives and is shared in the cloud.

The media industry is similar: The average age of a print newspaper reader in Sweden is 72. The paper and pulp industry has always been influential in Sweden, and we have traditionally provided much of the paper for newspapers all over Europe. Much of this production has been forced to close, however, in Sweden and Finland as the demand for newsprint has gone down.

Despite these challenges, Sweden has managed to harness evolving technologies, making it a hub for entrepreneurship and growth. We pride ourselves on being an economy that’s very open to the outside world—both in terms of trade, and in terms of immigration. Migrants have brought a new impetus and a fresh dynamism to the Swedish economy. We are a small nation—10 million people isn’t much in a world of 7.3 billion—and yet we are the birthplace of Ericsson, Volvo, and Saab. Our ability to embrace changes in technology as well as talented individuals arriving from abroad has allowed us to create and support an impressive roster of global corporations.

These factors are not just unique to Sweden, of course; many of them can be replicated. Estonia, for example, is also very small—around 1.3 million people—and very young. Yet, it is now starting to become one of the leaders in the use of digital technologies, particularly in e-government and security.

Another standout nation is South Korea. Due in large part to a very determined policy of digitization, it is now the most connected society in the world and boasts very high internet speeds. Meanwhile, its vigorous entrepreneurial environment has been churning out a long list of successful apps and has birthed some of Asia’s biggest brands.

Still, with connectivity comes risk.

In the Internet Governance Report, I discuss how the future of the internet hangs in the balance. The internet isn’t just about opportunity. It can also unleash dangerous new forces on the world: malicious data breaches, uneven and unequal financial gains, and cyber crime. It can also allow unscrupulous governments to manipulate their citizens in new ways.

To combat this, we must advocate for the human rights of digital citizens. The UN Declaration of Human Rights was written before the digital age. It applies to the freedom of speech, the freedom of information, the right to be respected, and the right to privacy. Now we need new, strict laws regulating when the legal authorities of a country should interfere with people’s private lives. We also need to extend the rule of law to cyberspace, to ensure that our legal systems are as prepared for online crimes as they are offline. Innovation and growth require legal certainty, not a Wild West mentality.

Ultimately, I’m optimistic about the way in which technology and the opening of borders are transforming our world. But I am also worried by the increasing tensions within societies facing change and disruption—the Brexit vote is one expression of that.

There is a real risk that political disenfranchisement in the United States and across Europe could have negative effects on our economies and political structures. Since the industrial revolution, society has continually come up with ever more creative ways to change the world through technology. However, each new generation must rediscover how to channel these changes for the good of all.