The Exxon Tillerson left behind: hidebound, secretive, and wedded to tradition at a time of mind-boggling change

Last November, ExxonMobil made a bombshell announcement. At a time experts thought all the supergiant oilfields on the planet were already discovered, the company revealed Liza, an “elephant” in industry parlance, 3.4 miles (5.5 km) beneath the waters of the Atlantic Ocean east of Guyana. In a rare rush, the company decided to start pumping Liza’s 1.4 billion barrels of crude as fast as possible, for shipment by 2020, a substantial feat in a South American hinterland lacking nearly every type of basic infrastructure.

Last November, ExxonMobil made a bombshell announcement. At a time experts thought all the supergiant oilfields on the planet were already discovered, the company revealed Liza, an “elephant” in industry parlance, 3.4 miles (5.5 km) beneath the waters of the Atlantic Ocean east of Guyana. In a rare rush, the company decided to start pumping Liza’s 1.4 billion barrels of crude as fast as possible, for shipment by 2020, a substantial feat in a South American hinterland lacking nearly every type of basic infrastructure.

But that was only the beginning. Around the same time, Exxon announced the discovery of a large oilfield in Nigeria, finalized negotiation for a natural gas field in Mozambique, and started drilling in Liberia. Then, on Jan. 17, Exxon announced the biggest new hit of all—the purchase of Texas shale acreage containing some 3.4 billion barrels of oil, the equivalent of three supergiant fields.

The message is clear enough: Exxon is, and will long continue to be, foremost an oil company. Never mind possible disruptions from a change in social tastes. Exxon is doubling down on tradition, with a zeal that harkens back to a time when oil was the undisputed commodity of the moment and the future.

Yet, notwithstanding these blockbuster discoveries, Exxon has been struggling. The strains include the most turbulent period in business and politics in modern history, a threat from competing technologies, and, after two years of low oil prices, doubts about the economics of fossil fuels as the principal motive actor in the $78 trillion global economy.

Of course, success in oil has always required surviving, and exploiting, mortal crises such as today’s—chaos, reversals of fortune, outright bankruptcy, sometimes all at once. Exxon’s 19th century pioneer, John D. Rockefeller, was an unyielding master of these trials. In the 1870s, he reached the top of the oil industry and stayed there by cutting costs ruthlessly, accounting for every penny, and unsentimentally lowering prices to “sweat” weaker-willed rivals who refused to be bought out.

In the century and a half since, Rockefeller’s heirs—the bosses of Exxon—have held fast to his methodical practices to remain a towering force in oil. It is a special darling of Wall Street, an attitude- and tradition-led gargantuan that operates in mysterious and obsessive secrecy, and quiets any investor restiveness with reliably rising dividends.

And, in ordinary times, the company might have been considered ingenious. But the age has seemed to conspire against it.

Exxon is doubling down

Over the decades, Exxon shareholders have had reason to keep faith: A $10,000 investment in the company’s shares two decades ago, with dividends reinvested, would be worth about $60,000 today, for an annual return of 9.3%. That’s tremendous profit for a widows-and-orphans play considered nearly as safe as US Treasury bonds. Meanwhile, it is regarded as one of the most environmentally cautious companies in the industry, if not out of conscience, then because accidents and oil spills are bad business.

But Exxon’s fortitude has been tested as oil prices have languished between $27 and $55 a barrel. More than 100 smaller North American producers have filed for bankruptcy since prices slid from more than $100 a barrel.

Over the last two years, Exxon has taken on about $24 billion in debt, had its credit rating downgraded for the first time since the Depression, and stopped buying back its shares, its customary tool for propping up its stock price. Oil prices have turned back up—the US-traded WTI benchmark has rebounded off its lows by 36%, and international Brent crude by a whopping 45%. But Exxon’s stock price has lagged behind resurgent competitors like Chevron and ConocoPhillips, and, according to data supplied by S&P Capital IQ, in the first three quarters of 2016, the company had used about $6 billion in debt or asset sales to cover its quarterly shareholder dividends. (The company will disclose its fourth-quarter results on Jan. 31.) And, notwithstanding its strong record avoiding oil spills in recent decades, Exxon has taken a beating as newspaper probes have accused it of disregarding internally produced studies suggesting that fossil fuels could cause global warming, while funding a campaign to discredit climate science.

The upheaval has not wholly disadvantaged Exxon, however. In yet another of the drumbeat of recent surprises, US president Donald Trump has tapped longtime Exxon executive Rex Tillerson as his secretary of state, prompting Tillerson to retire from the company in December, a few months ahead of schedule. On Jan. 23, the Senate Foreign Relations Committee confirmed Tillerson’s nomination, which now goes for a vote by the full Senate, where he is all-but certain of approval.

The appointment could be a boon for Exxon: For more than two years, the company’s largest single concentration of future oil production—colossal reserves in Russia—has been suspended because of US sanctions over the invasion of Ukraine. Exxon discovered a 2.7-billion-barrel field in Russia’s Arctic, and has access to the largest shale oil field on the planet, located in Siberia. But it has been able to do nothing with either. Tillerson, who has a longstanding working relationship with Russian president Vladimir Putin, could help Trump to thaw relations with Moscow, as Trump says he’d like to do. And if Tillerson can, that could free up Exxon’s Russian reserves.

Whatever is to come, Tillerson’s successor as CEO, Darren Woods, is likely to follow the same, Rockfellerian path as his predecessors. And therein may lie Exxon’s fate.

Two deals tell the tale

Like the rest of Big Oil, Tillerson missed the onset of the shale revolution, as nimbler independent companies created the breakthroughs and grabbed the best real estate. But in 2009, he acted to turn things around. In a colossal deal, Tillerson acquired the premier fracking pioneer of them all: XTO Energy, the third-largest gas producer in the US. Negotiating the purchase himself, Tillerson paid a considerable $41 billion, all of it in Exxon stock. Critics scoffed that Tillerson had paid too much, but his defenders noted that at once, Exxon was enviably positioned in the shale revolution—much better than other major oil companies.

While his defenders were right, what they and Tillerson weren’t taking account of was just how revolutionary shale was. Soon, so much shale gas was flooding the market that the price plummeted from $5 to under $2 per million Btu, and the acquisition weighed on Exxon earnings. From the outset, Tillerson had cautioned that the XTO deal was aimed not at instant profit, but long-term returns over the decades. Still, the brutal market consensus now was that the acquisition was vastly overpriced. Tillerson was looking much less olympian than his Exxon predecessors.

Two years later, Tillerson got a shot at another substantial deal. In Russia, BP had bungled a coup of its own. It had joined forces with Rosneft, the Russian state-owned oil company, to explore some of the most promising Arctic and shale oil fields in the world, containing tens of billions of barrels of potential oil reserves. But it had ended up crosswise with former Russian partners, well-connected oligarchs who wanted a piece for themselves. In Russia, that is a group you just don’t cross, and BP ended up having to pull out.

Tillerson, alert to the opportunity, swooped in. Within three months, he won roughly the same arrangement as BP. This time there were very few skeptics—it was true that Russia seemed a risky place to do long-term business, but in cold-eyed realism, the oil reserves appeared to be so large that for a generation, they would fulfill Exxon’s long struggle to find enough oil.

Tillerson could not have predicted that, just three years later, Putin would invade Ukraine and initiate the greatest East-West confrontation since the Cold War.

This bad luck, for Exxon and Tillerson himself, exacerbated the industry turmoil. Even with a record of new discoveries resembling the old iconic wildcatters, Exxon has had trouble replacing the reserves it had expected from Russia. In February, it announced that, for the first time in two decades, it had failed to replace the crude it drilled in 2015, replenishing only 67% of its supplies.

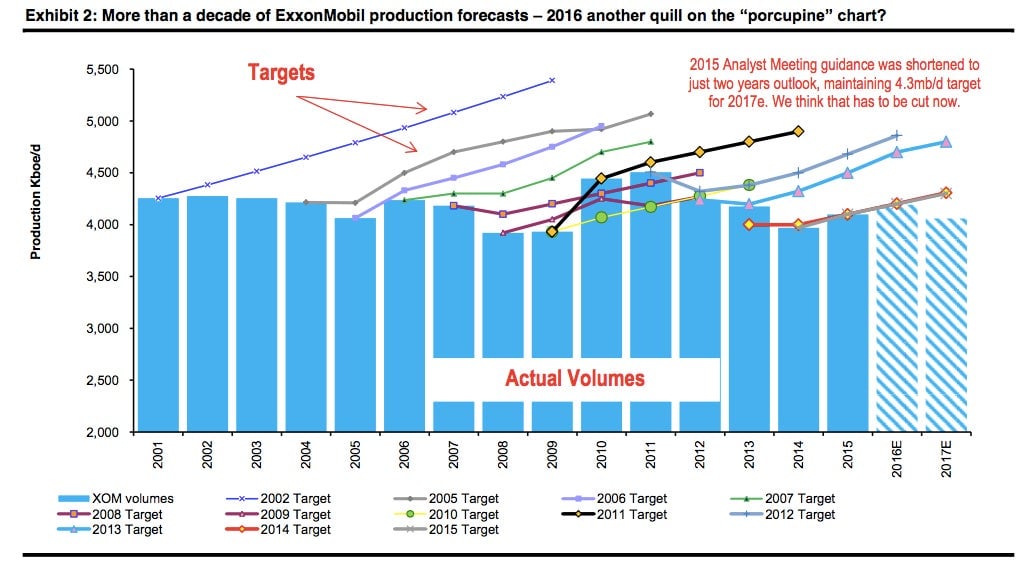

In March 2015, Tillerson lowered production guidance he had given two years earlier. Instead of drilling 4.7 million barrels of oil a day in 2017, he said, Exxon would deliver between 4 million and 4.2 million all the way through 2020, or just a little above the 3.8 million barrels a day it produces now. Finally, in October, the company stunned the market with the announcement that low prices will force it to write down perhaps a fifth of its 25 billion barrels of proven reserves. How much precisely Exxon will wipe off the books is not yet known, but it may be a whopping 4.6 billion barrels.

Exxon has seen it all—its creation in the US Supreme Court-ordered breakup of Standard Oil in 1911, the Arab-led nationalizations of the 1970s, the oil price collapses of the late 1980s, the 1990s and the 2000s, not to mention the numerous crises in between. Through everything, Exxon has almost always financially outperformed its rivals by a substantial margin, and has thus been given latitude by Wall Street to carry out its inscrutable ways largely in secret.

But Exxon’s recent profitability has been much less impressive. Analysts expect that in 2016, the company once again failed to fully replace the oil it drilled during the year. (The numbers will be reported in February.)

If Exxon gets its Russia reserves back, that will put the company back on a successful track. But until then, to justify confidence in Exxon’s future—in its ability to keep paying its 3% dividend while losing money, for instance—it will be under pressure from Wall Street to start revealing more of its internal metrics. “There has been a constant frustration with ExxonMobil’s lack of disclosure of many elements of its business,” Paul Sankey, an analyst with Wolfe Research, told his clients in a September note. “For many years, we have argued to the company itself that if it is as superior as it claims, surely more disclosure would help its investment case.”

If so, Exxon might start with the mystery of its 91 billion barrel resource base.

Where is the meat in Exxon’s world of oil?

Every year around February or March, Exxon boasts about its “resource base.” At 91 billion barrels, it is larger—far larger—than any competitor’s; its next-largest American rival, Chevron, has 68 billion barrels, for instance.

To understand why this is such a big deal, the resource base refers to every single barrel of potentially produceable oil under Exxon’s control—what is, under Securities and Exchange Commission rules, definitely proved reserves, plus a lot of other oil that management thinks has a very good chance of being economically delivered to market. Of Exxon’s last-reported resource base of 91 billion barrels, 27% is “proved.” The rest has between a 10% and a 90% chance of being produced, according to industry definitions. But whatever category we’re talking about, Exxon says every year that it expects at some point to produce and sell all 91 billion barrels—that they will “be ultimately recovered in the future.”

But is this true? Are all those barrels of a quality that can be produced one day? And if so, on what time scale? To answer these questions, consider two facts about Exxon. The first is that, despite its advantageous resource base, it has missed its own production target almost every year since 2001 (see chart below from Wolfe Research). In 2001, Exxon said it would be producing more than 5 million barrels of oil a day by 2009; instead the number was about 4 million. In 2009, the company said its 2015 production would be about 4.5 million barrels a day; again, it was around 4 million. And so on. Exxon’s production has remained almost flat for the entire 15-year period.

Which begs the question whether the undeveloped barrels are anything really to brag about, or if they are instead more or less notional. Should Wall Street be taking any barrels into account apart from Exxon’s 25 billion proven barrels? The answer is certainly yes for tens of billions of the remaining base. But what about the rest? Is some of it simply dead weight, at least at the oil and gas prices of the last two years?

What is stuck at ExxonMobil that it usually cannot reach its production targets?

Another curious thing about Exxon’s resource base is that the company does not provide an inventory of it. There is no public list of all its fields, with the gross number of potential barrels, all of them adding up to 91 billion. None of Exxon’s major rivals—Chevron, Shell, Total and BP—provides such a list, either; and all have faced similar missed targets over this period. But what distinguishes Exxon in this regard is its history, its heft, and its reputation as the most capable of the oil giants—not to mention its outsized boastfulness—which combined make its spectacular misses and its outsized secrecy loom larger.

In reply to questions about production and its resource base, an Exxon spokesman directed me to this website, which is from the company’s annual analysts’ meeting in March. The site does not explain the resource base nor why the production guidance is chronically missed. I asked the spokesman whether that was the entirety of his reply. He did not respond.

The vacuum of data has forced the community of analysts paid to watch Exxon either to take its word, as it has for decades, or turn to outside estimates of the resource base by research firms such as Wood MacKenzie. But Wood MacKenzie says its list is unavoidably incomplete since Exxon is not transparent, and that shale and oil sands are especially difficult to estimate. Its numbers add up to about 82 billion barrels, 9 billion off the number Exxon has reported. Where is the discrepancy? Who can say?

The oil industry as a whole is extraordinarily tight-lipped, and always has been. But a special mystery has traditionally surrounded Exxon, an aura that, according to Steve Coll, the author of Private Empire, a book on Exxon, led some employees themselves to dub their Irving, Texas, headquarters “Death Star.” Its opaqueness served Exxon well during its many decades of bare scrutiny by investors and Wall Street, allowing executives to go about their business without inference from outsiders.

But neither oil nor Exxon are the sure things they once were. In most places, when you only partly disclose, you suggest that you are hiding something.

Electric schmelectric

On Dec. 13, three Chevy Bolts arrived in the hands of buyers in Fremont, California. The deliveries made GM the first mover in an entirely new industry category—the long-range, mainstream-priced electric car. The Bolt is the American carmaker’s $37,000 pure electric car (see below, right). It goes 238 miles on a single charge, and is the forerunner of a coming deluge of such vehicles from most of the major carmakers over the next few years. GM’s choice of place for the launch had much significance—Fremont is the headquarters of Tesla Motors, the pretty boy of electric cars, the contrarian company whose cool has validated the commerciality of electrics. Next year, Tesla plans to release the Model 3, its own mainstream electric (pictured above). Motorists have already placed $1,000 deposits on almost 400,000 of the Model 3s, making it an instant hit. Yet GM, getting to the market first, was taunting Tesla in its own backyard.

Less deliberate but just as cutting, GM was also poking a finger in the eye of Exxon. With its launch of mass-market electrics, GM buttressed forecasts of an age of plunging oil demand and the slow destruction of oil companies and petro-states that do not adapt.

According to research from Bloomberg New Energy Finance (BNEF), a plummet in the cost of batteries is leading to a crossover point at which electric cars will be cheaper to own than gasoline or diesel models. That inflection point is about the middle of the next decade.

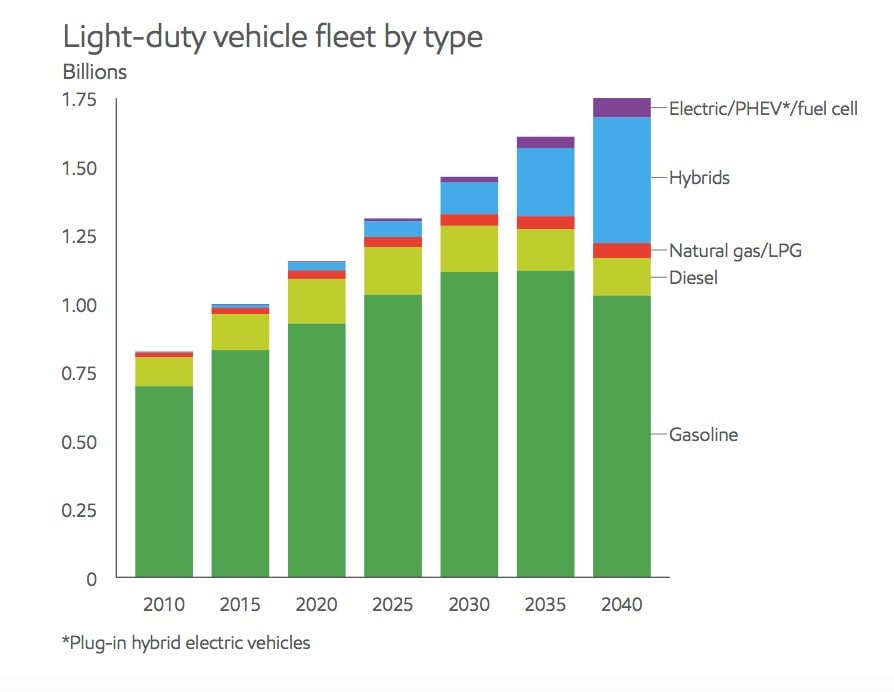

If accurate, that will help to trigger a leap in electric car ownership. By 2040, BNEF says, electrics will account for 35% of all new car sales, meaning almost 50 million electric vehicles sold a year. Elegant styling and a shift in social taste are primary reasons for BNEF’s bullish forecast. Another is politics—the polluted air in Beijing, Delhi, and a slew of other Chinese and Indian cities is leading the ruling class in both countries to pivot away from oil, including the discouragement of conventionally fueled vehicles. In all, BNEF forecasts a drop-off in traditional car sales, and by extension the demand for fuel; it projects that oil consumption will drop by 8.6 million to 13 million barrels of oil a day.

To grasp the significance of such a reduction, the two-year plunge in oil prices and all the attendant misery ladled onto petro-states and oil companies are the result of an added 4 million barrels of oil a day of production, all of it from US shale fields. At double or triple that volume, as BNEF and other research firms are forecasting, oil prices could crater, creating mayhem for Exxon, the rest of the oil industry, and for petro-states.

In the 1970s, Exxon actually invented the lithium-ion battery, then let others take the lead when oil prices revived. So, in the bowels of the company, is its research team hard at work at a surprising breakthrough in electric mobility?

Judging by its pronouncements, the answer is no. Rather, Exxon appears not to believe the bullish outside analysts. Its corporate annual reports, including routine filings with the SEC, disclose a belief that a breakthrough in electric cars—either a technological leap or a consumer mania for them—could materially impact oil demand. But it doesn’t expect any such advance or consumer fever, at least for the next quarter century. But the company’s latest long-term outlook, released in December, does project that in 2040, small-battery hybrid cars—like today’s Prius—will account for 25% of the cars on the road.

An interesting part of the Exxon forecast is that “short-distance” pure electrics may rise to over 10% of sales. That is a much smaller number than BNEF forecasts, but is considerably larger that the few percentage points the oil company predicted just a few years ago. Exxon is casting doubt on electrics, which it says will have trouble fully penetrating the market because of cost and technological limits. But that its forecast is in motion seems to show its skepticism softening; if the company’s forecasters shift their sales target much more, it is going to start looking a lot like a rear-guard defense.

But oil demand, too, is no sure bet

Until just a half-dozen years ago, doomers were all the rage. If you knew none, these were people who were gathering their stuff and moving to a wary life in the woods, convinced that oil was running out, that the world was about to break out into a resource war, and that it would be every man for himself.

Less than two years later, the shale oil deluge washed away such gloom. That was followed by a new worry, which was that the plunge in oil prices triggered by the shale oil would shatter the petro-states, exacerbating the already-catastrophic tumult in the Middle East. But a new unity within OPEC has seemed to establish a $50-a-barrel floor in oil prices, and thus—at least for now—dispelled the visage of collapsing oil monarchies.

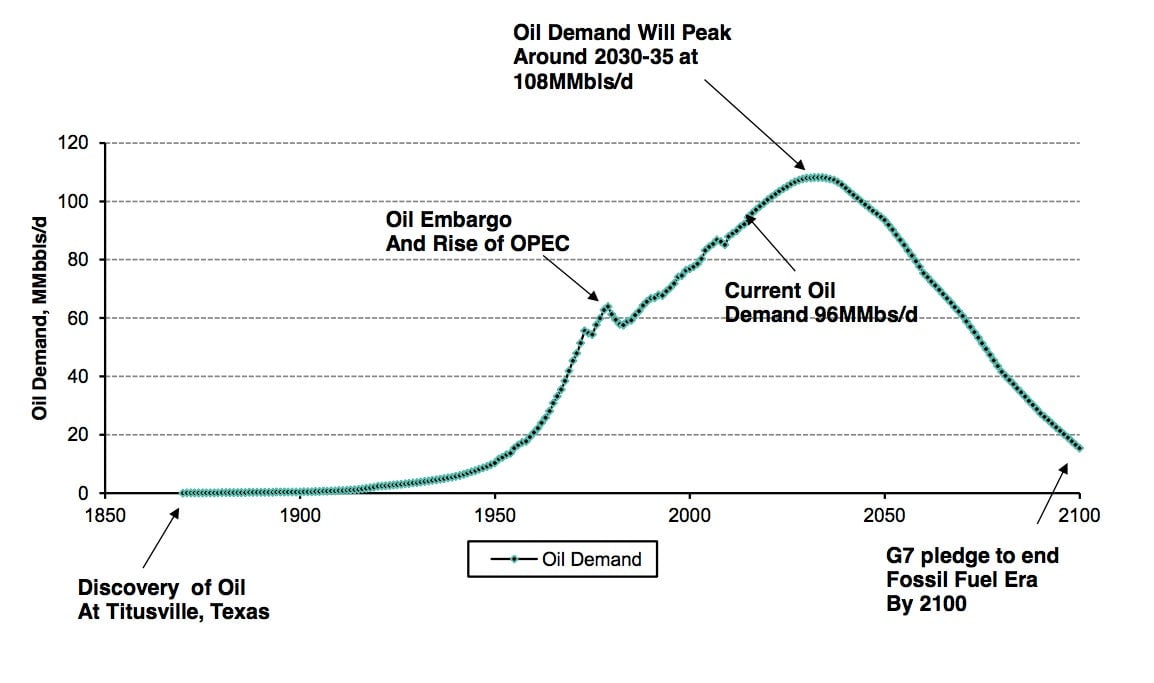

Even in an age of one damn unpredictable thing after another, the future of energy and mobility may be the most unknowable of all. But that has not discouraged irrepressible forecasters, whose newest prediction is gaining adherents. It is a twist on the discredited theory of “peak oil”—the doomer belief that petroleum supplies were quickly running out. They call it “peak demand,” which posits that trends like the advent of new electric cars and an increase in the efficiency of conventional cars are naturally leading to a plateau of oil consumption. They say this point will be reached in the next decade or so (see chart below).

Sensibly speaking, oil is not going away, at least not this century. Even if every ordinary motorist on the planet turns to electrics, millions of barrels of oil a day will still be consumed in factories, on airplanes, in trains, in ships and in trucks. Nor are oil companies going to shut in their current fields, because the decline—if it happens—will take place over a period of 70 years or longer, and companies can still make good money in the meanwhile finding and producing oil.

But in the interregnum, according to this thinking, the demand will inexorably vanish. And to the degree it does, the question will be whether Exxon and other oil companies morph or vanish with it.

Publicly, Exxon says that not only will demand not peak, but that it will rise by 20% by 2040. So for this company, it’s more or less business as usual, a posture defended by the International Energy Agency, which agrees that oil demand will keep rising through 2040.

But on Nov. 1, Shell broke away from the pack. Its chief financial officer, Simon Henry, joining the peakers, said oil demand could plateau in five to fifteen years. Since then, other companies and mainstream analysts have taken a similar position, including even OPEC. The cartel, like many of the forecasts, places heavy emphasis on the demands of the so-called Paris Agreement, the climate change accord in which more than 100 countries have made aggressive pledges to reduce CO2 emissions, vows that, if fulfilled, will significantly reduce how much fossil fuels are burned.

Current politics in the West, notably Trump’s vow to dismantle the Paris accord, suggest considerable uncertainty that the pledges will be fulfilled. But other powerful forces are driving a decline already. As noted above, one is a potential transformation of how the human race transports itself—the electrification of cars. According to Bernstein Research, the combined impact of the mass-penetration of electric cars and energy efficiency will be so powerful that, by the end of the century, oil consumption will plunge below 20 million barrels a day, from about 95 million today (see chart below).

When describing this future, analysts speak not only of peak demand, but of “peak car,” a time not far in the future when people around the world—mainly for reasons of personal taste—buy far fewer vehicles. Tom Armstrong at IHS forecasts peak car in 2025, leading to a cap in gasoline consumption the same year. These are numbers that, if they occurred now, would mean utter catastrophe for petro-states and oil companies, and—because of the proportional size of the global oil economy—quite possibly a serious worldwide recession.

So it has been notable that, against such forecast headwinds, Exxon has elected to bull forward as though the oil age will proceed unhindered. The company does not speak of a peak at all. Through 2040 and beyond, oil and gas will still account for about 56% of the world’s energy demand, Exxon says in its latest outlook. That is about the same percentage as today, only with a shift to a bit more gas and a little less oil.

One force that Exxon may be underestimating is expectation. As increasing numbers of serious players become persuaded that demand is uncertain, you could start to see adaptive behavior, in addition to some panic. Shrewder OPEC countries will recalibrate production—if they think there is a relatively near horizon, some may let loose in hellbent drilling and refuse to invest any further into their fields, thus inviting even more chaotic market conditions. Cooler heads could argue that greater cartel discipline will extend the age of oil. But all eyes will be on China and India—if their collective demand growth does not fully compensate for declines elsewhere, the panickers could win the day.

The potential geopolitical consequences include pandemonium. The countries most vulnerable to chaos are Nigeria and Venezuela, places that are already unstable. But if the last decade is informative at all, it’s that anything can happen. If the global economy plunges into deep recession, the US itself could be shaken, just as it has by the European populist political wave.

This should be precisely the time when investors rush to Exxon as a safe harbor. But with many market players perceiving a permanent shift in how the world is both powered and ruled, will Exxon follow its traditional strategy of simply holding the tiller steady? Will it still be that safe harbor?

Will Exxon become something else?

The signs of a coming new age are unmistakeable. Just ask Mohammed bin Salman, the most powerful 31-year-old in Saudi Arabia, perhaps in the world. In a campaign that he calls “Vision 2030,” Saudi’s deputy crown prince, persuaded by the peakers, is attempting to set in motion a transition to a market economy gradually far less reliant on oil exports. Prince Mohammed has already invested $3.5 billion in Uber and announced a $1 trillion fund to pour money into non-fossil fuel assets, including Silicon Valley technology. The ultra-secretive crown jewel—the state-owned oil concern Aramco—is going at least partly transparent in order to sell up to a 49% slice to the market over the next decade. It is a revolutionary and—if you think that oil demand is indeed peaking—a visionary act, setting Saudi Arabia apart from almost every other petro-state.

Prince Mohammed’s plans also contrast with those of Exxon, which on a number of fronts seems to be fighting the last war. One such front is its legal fight over all-but settled climate science. For the last year, federal and state prosecutors have subpoenaed a trove of company documents in probes of whether Exxon’s public financial disclosures have adequately accounted for the potential impact of climate change on the company. Typically, Exxon has furiously denied media accounts of Exxon’s climate history, and filed actions to quash the investigations, issuing counter-subpoenas seeking emails and other documents from the prosecutors’ offices. Adding a surreal quality to the drama, Exxon has also subpoenaed documents from an arm of the Rockefeller family itself, accusing it of orchestrating a campaign against the company that’s known by the hashtag #ExxonKnew.

If Exxon were being straight-forward on this subject, it would lay out the facts, which are that company scientists working for his predecessors in fact did establish a potential link between fossil fuel emissions and climate change, but that ultimately the company decided to disregard their peer-reviewed studies on the subject, just as newspaper investigations have alleged. And it would fess up explicitly that Tillerson’s immediate predecessor, then-CEO Lee Raymond, was the leading actor in an aggressive campaign to discredit climate scientists who were gradually documenting the same link.

In fact, Tillerson more or less did that in 2009, weeks before Barack Obama began his first term in the White House. In a calculated move because of the politics of the early Obama presidency, Tillerson began to walk back Raymond’s ideological fetish, without explicitly saying so, and he continued to do so until he left the company when he was nominated by Trump.

Tillerson’s successor—Woods, a 51-year-old refining expert—will still have to deal with the prosecutors. But another step forward in candor can only improve Exxon’s reputation, and allow Woods to begin to address the next war, which is how Exxon adapts to the new world.

The rise of Trump and the addition of Tillerson to the State Department could significantly restore Exxon’s fortunes by reviving its projects in Russia. But the reality of low oil prices and harsh drilling conditions may result in Exxon banking the reserves from Victory, as Russia named the Arctic field the American company discovered in 2014, for years before actually producing the oil. Shell, for example, abandoned drilling in Alaskan Arctic waters a year ago, despite finding oil; in 2012, France’s Total said it would never drill in the Arctic because a catastrophic spill would exact too high a reputational cost. Exxon, too, could decide to go slow.

The price of oil will be a big question mark over the Victory field. Amrita Sen, an analyst with Energy Aspects, forecasts temporarily tighter oil supplies over the coming two years and a spike of oil prices to $98 a barrel. But that will generate new excitement on the US shale patch, and a plunge to $78 in 2020, Sen says. Others are much more pessimistic about oil prices. The futures market, for instance, is betting that oil stays below $60 a barrel through March 2024. Safe to say, not even Exxon could make money in the Arctic at $60 a barrel.

Of course, the politics of dealing with Putin may require Exxon to proceed with Victory anyway. For Putin, the Arctic is Russia’s only currently known economic driver for the 2020s and beyond. The country relies on oil and gas revenue for more than half the state budget, and much of its GDP growth. So, if sanctions are revoked, Exxon may be pressured to drill Victory regardless of whether it’s profitable. As a sweetener, Exxon could be permitted to proceed with more commercial acreage to which it also has access, in Russia’s vast west Siberian shale, known as Bazhenov. The Bazhenov shale, according to Russia’s energy ministry, contains an astounding 30 billion barrels of oil. Conditions there are difficult, but not on the scale of the Arctic. Exxon has a lot better chance making money there.

Exxon is not dying now or soon. Sankey, the analyst from Wolfe Research, said in a Jan. 17 note that the company’s recent discovery-and-acquisition binge demonstrates that it is taking its challenges seriously. Exxon’s trouble will come in the long term if it got electrics wrong, or if demand falls off the cliff. The company has made a one-way bet on oil in an extremely uncertain situation. Exxon’s ultimate Rockefellerian bet would be to muscle up, husband resources, and wait out the sweating going on all around it. As in the 1870s, it may find most of its rivals dropping like flies, allowing Exxon to pick up their assets at fire-sale prices. When demand is down to 20 million barrels a day, Exxon could command a strong fifth of it, and go on being the colossus with which we are familiar into the next century.

The biggest problem with such a strategy is the profound unpredictability of our age. If Exxon’s answer to the commotion around it is to stand still in apparent confidence that it either can withstand any blow and thrive in the aftermath, it can do so. Since Rockefeller, that tried-and-true strategy has served the company well. The question is who outwits whom on this occasion—Exxon or the times.