When it comes to China, Trump is stuck in the 1980s, thanks to the Cold War-era advisors surrounding him

US president-elect Donald J. Trump said that he doesn’t want to be “bound by a ‘one China’ policy,” the US’s decades-long stance of treating Taiwan and China as the same country. Instead, he plans to use the issue as a bargaining chip, he said Dec. 11, to “make a deal” with China on trade and other issues.

US president-elect Donald J. Trump said that he doesn’t want to be “bound by a ‘one China’ policy,” the US’s decades-long stance of treating Taiwan and China as the same country. Instead, he plans to use the issue as a bargaining chip, he said Dec. 11, to “make a deal” with China on trade and other issues.

The concept is as out of date as Trump’s completely erroneous stance on Beijing’s currency, which he demonstrated on the campaign trail and after the election, Chinese analysts and scholars say. (Trump has insisted again and again that China is artificially weakening its currency to increase trade, a situation that hasn’t actually been true since the 1990s.)

By trying to use the island as a bargaining chip, Trump is harking back to the White House’s approach to the US-China relations throughout the 80s and the 90s—an approach that changed drastically under presidents George W. Bush and Barack Obama, as world’s biggest economies became more intertwined.

Trump’s throwback approach comes because he has surrounded himself with outdated, Cold War-era advisors who have had little exposure to China since then, analysts including Shen Yi, an associate professor at the School of International Relations and Public Affairs of Shanghai’s Fudan University, say. Trump is playing a “classic Taiwan card” once played by Republican presidents including Ronald Reagan and George H. W. Bush, Shen said.

“Trump’s message was clear: I don’t want to fight against China, but you are not following my way in many issues including trade and the South China Sea [dispute]… so I’ll exert some pressure on you,” Shen told Quartz. The approach is dangerous. An actual military war between the world’s two largest economies is a very unlikely prospect, he said, but a trade war between the two that threatens the global economy is not.

Back to Reagan

Rather than threatening to recognize Taiwan outright, Reagan escalated the sale of military equipment to the island, despite an agreement to the opposite.

On August 17, 1982, the US and China issued a joint communiqué that agreed the US will gradually reduce its arms sales to Taiwan. But earlier in July, Reagan also pledged to Taiwan that the US would not set a date to cut off the arms sales, and “would not formally recognize Chinese sovereignty over Taiwan,” among other promises together known as “the Six Assurances.” These guidelines have been confirmed by each successive US administration.

To complicate matters, Reagan issued a confidential presidential directive, on the same day of the communiqué, saying that the US’s willingness to reduce its arm sales to Taiwan only stands if China solves its differences with Taiwan by peaceful means. The very next day, the White House even announced the sale of 250 F-5 fighters to Taiwan.

“Alas, since then, Beijing’s threat [to Taiwan] has only increased, as have U.S. arms sales to Taiwan,”a retired US foreign service officer wrote in the National Interest, a US foreign policy magazine.

In 1992, for instance, Bush Sr. approved the sale of 150 F-16 jets to Taiwan, and Beijing retaliated by threatening to quit international arms control talks and selling missiles to Pakistan. Since then the US hasn’t sold fighters to Taiwan despite several request from the island authorities in the 21st century. (It has continued defensive arm sales that would trigger less negative reactions from Beijing, under the 1979 Taiwan Relations Act.)

The tensions didn’t stop with Bush Sr. In 1995, when Bill Clinton was president, Taiwan tensions almost sparked a war between China and the US, when he granted then-president Lee Teng-hui a visa for a “private trip” to the US, and Beijing objected angrily and physically. Between 1995 and 1996, Beijing conducted a series of missile tests in the waters near Taiwan. In response the US dispatched its biggest combat forces to Asia since the Vietnam War, including two aircraft carriers, to the area, forcing Beijing to soften its stance.

Anti-terror cooperation

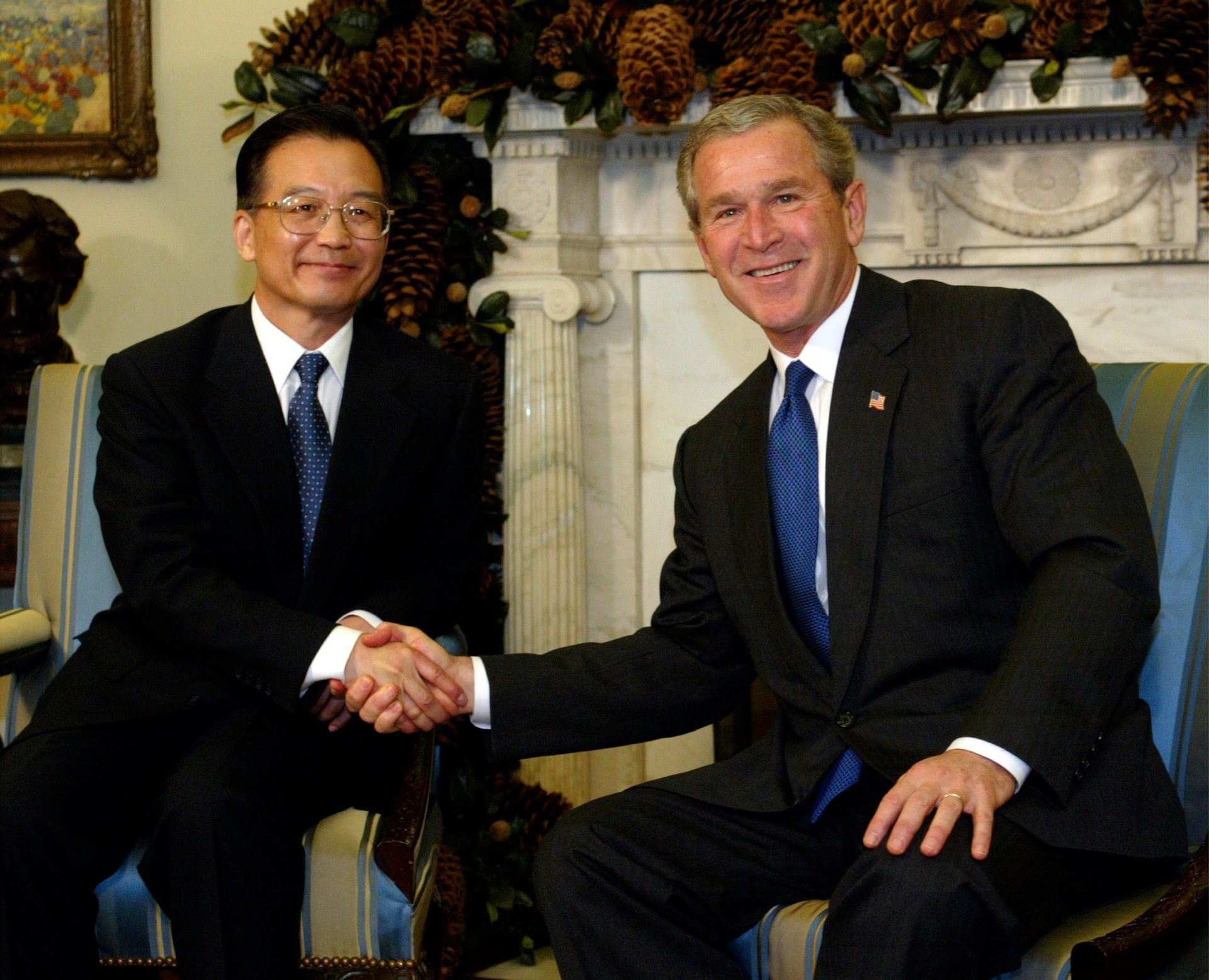

Such conflicts essentially died down during the later period of the George W. Bush administration, because Taiwan was no longer a “core issue” of US-China relations, Shen said. Instead, the two countries forged an unexpectedly supportive anti-terrorism alliance after the attacks of Sept. 11, 2001. That was especially apparent when Taiwanese president Chen Shui-bian pushed hard for independence in 2003. Bush Jr. reassured Chinese premiere Wen Jiabao during his visit to the White House that the US opposed “any unilateral decision by either China or Taiwan to change the status quo.”

Under Obama, the US-China relationship has moved past cross-Strait relations to broader regional issues such as the now-defunct TPP trade deal and the South China Sea, as China became more important economically and in Asia, Cheng Li of the Brookings Institution wrote in August. Obama stressed the need for the US to “integrate itself into a changing world rather than stomp around arrogantly and blindly,” Li noted.

Trump’s foreign policy advisors, though, largely “favor a more hawkish attitude toward China,” said Fudan’s Shen, and want to challenge the status quo. Their premise appears to be that ”the US is stronger than China,” said Shen, rather than that the two sides should maintain a delicate balance.

These people “have been left out in the cold for decades since the Cold War concluded,” Shen said, and are “far out of touch of the battlefront of the US-China relations.”

The Trump team thinks that “international relations are a zero-sum game—a new rising power will inevitably have (military) conflicts with an established major power,” Han Xiao, a PhD candidate at the University of Hong Kong who specializes in Asia-Pacific security studies, told Quartz. Instead, a mixture of “engagement and containment” is key to maintain stability of the US-China relations, Han noted.

Trump’s pick for national security advisor, retired Lt. Gen. Michael Flynn, who is known for anti-Islamic rhetoric, has linked China and North Korea to Islamic jihadists in a co-authored book published in July. The US needs to confront an alliance between “radical Islamists,” the two Communist states, and Russia, he writes—a viewpoint that has been roundly mocked by foreign policy experts and diplomats in from the US to the Middle East to China.

A child’s tantrum as foreign policy

Over the past weekend, tensions escalated into physical conflict after China seized a US underwater drone operating in the international waters in the South China Sea. China’s defense ministry said it will return the drone at Pentagon’s request, but Trump—again—took to Twitter to suggest something very different.

The Twitter remarks baffled China-watchers, Beijing, and average Americans alike. Some compared the president-elect’s apparent sarcasm about “keeping” the drone to a toddler’s tantrum.

During a year-end press conference at the White House on Dec. 16, after China’s seizure of the US drone, Obama said that if Trump is going to scrape the “One China” policy, he’d better have thought through what the consequences are. “[The] status quo, although not completely satisfactory to any of the parties involved, has kept the peace and allowed the Taiwanese to be a pretty successful economy and a people who have a high degree of self-determination,” Obama said.

On foreign policy in general, Obama suggested Trump get a full team in place, and get fully briefed on what’s happened in the past and where the challenges and opportunities are, before starting interactions with foreign governments. “You want to make sure that you’re doing it in a systematic, deliberate, intentional way,” he said.

China advisors who don’t know China

During Obama’s eight years in office, his China advisors included Jeffrey Bader, Asia chief on the National Security Council, who has a three-decade career with the government in US-China relations; James Steinberg, deputy Secretary of State from 2009 to 2011, who notably coined the term “strategic reassurance,” meaning competition can be limited to avoid conflicts, and particularly military conflicts, in the US-China relations; and Evan Medeiros, Asia chief on the NSC from 2013 to 2015, who was a visiting fellow at the China Academy of Social Sciences in Beijing and adjunct lecturer at China’s Foreign Affairs College in his early career, and speaks, reads and writes Mandarin Chinese.

Many of Trump’s most vocal advisors, on the other hand, appear to be mostly armchair China critics, who have spent limited or no time in China in the past two decades, as the country and Beijing’s priorities have changed dramatically. Not only do they not speak the language, they appear to have little to no experience interacting with China’s policymakers or understanding of how to negotiate with them. Here’s a rundown of the people analysts speculate were involved in his Dec. 2 call with Taiwan’s president Tsai Ing-wen, as Quartz reported earlier.

- Edwin Feulner (age 75), former president of conservative think-tank The Heritage Foundation, who wrote a 1976 book about China and the country’s “turning point” that is no longer in print.

- Reince Priebus (age 44), Trump’s incoming chief of staff, who visited Taiwan in October of 2015, but does not appear to have traveled to mainland China. He walked back Trump’s “One China” comments over the weekend.

- Peter Navarro (age 67), a Trump economic advisor known as his “muse” on China. The hard-line China critic’s “dangerous” views on China are so “radical,” the New Yorker reports, that no other economist supports them.

- Bob Dole (age 93), former Republican presidential nominee, who last served as senator twenty years ago.

- Jeff Session (age 69), Trump’s attorney-general nominee, who pushed a bill in 2011 to impose tariffs on Chinese goods to punish Beijing for manipulating its currency. The bill would spark a trade war, Chinese analysts said.

Quartz contacted the list to ask them whether they’d had any engagement with China’s government, analysts, or scholars in recent years, or had traveled to the country, but none replied. More than half a dozen American specialists on the US-China relationship declined to comment on Trump’s approach so far.

Stephen Yates, a former advisor to Dick Cheney, was said to be linked to Trump’s call but told Quartz he had nothing to do with the Trump administration. Michael Pillsbury, a hawkish former Pentagon official with China experience who was reported to be a Trump defense policy advisor, told Quartz he is not a formal advisor or member of the transition team.

Trump’s advisors “don’t have much to do with China,” HKU’s Han said. American scholars who do understand China better, including Johns Hopkins’ David Lampton, David Shambaugh of George Washington University, and Henry Kissinger, are not involved in Trump’s transition, Han said.

“My guess is that the people named so far have been to China too little or not at all,” said Richard Bush, a senior fellow at Brookings Institution said in an email to Quartz.

A looming breakdown

In a November article for Foreign Policy, Trump advisors Alexander Gray and Navarro criticized Obama’s Asia policy as “talking loudly but carrying a small stick,” saying it “has led to more, not less, aggression and instability in the region.” The duo laid out a starkly different path for Trump that they likened to Reagan’s “peace through strength” strategy, wherein Trump should show strong support for Taiwan, push back against China more generally in the South China Sea, and increase the US’s military presence in Asia.

Analysts not affiliated with Trump predict a much different outcome. In a recent open letter to Trump, Bush argued that Trump’s idea of using Taiwan as a “treatable good” to make deals with China would be ”immoral” and put the island itself at risk.

The world needs a “stable, but not necessarily intimate relationship” between the US and China, said Han. Rather than attacking China’s “core interests,” the US could contain China using trade pacts or deepening military alliances with its Asian allies, he said. If Trump “really wants to challenge China’s stance on the Taiwan issue, the Sino-US relationship will likely break down,” Han said.