Would you serve your family lab-grown meat? PETA would

Winston Churchill was one of the first public figures to believe that we would one day grow animal parts without the animal. In 1931, he predicted that by the 1980s, people would grow chicken breasts and wings rather than raising the entire bird. Although his timeline was a little off, Churchill’s vision for the future is now rapidly becoming reality.

Winston Churchill was one of the first public figures to believe that we would one day grow animal parts without the animal. In 1931, he predicted that by the 1980s, people would grow chicken breasts and wings rather than raising the entire bird. Although his timeline was a little off, Churchill’s vision for the future is now rapidly becoming reality.

In 1940, not quite 10 years after Churchill’s original proclamation, a Dutch researcher and entrepreneur named Willem van Eelen found himself sickened by the bloodshed of war. Earning himself the enviable title of “The Godfather of In Vitro Meat,” he began to explore the possibility of growing edible meat without having to slaughter animals. Following in his path, People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals (PETA) became interested in this kind of research around 20 years ago and has been helping fund labs and projects ever since.

Although it may at first seem strange for a vegan-advocacy organization to support the development of a new type of meat, if technology can help end animal suffering—in addition to reversing environmental damage, ending world hunger, and making our food supply safer—why wouldn’t PETA support it?

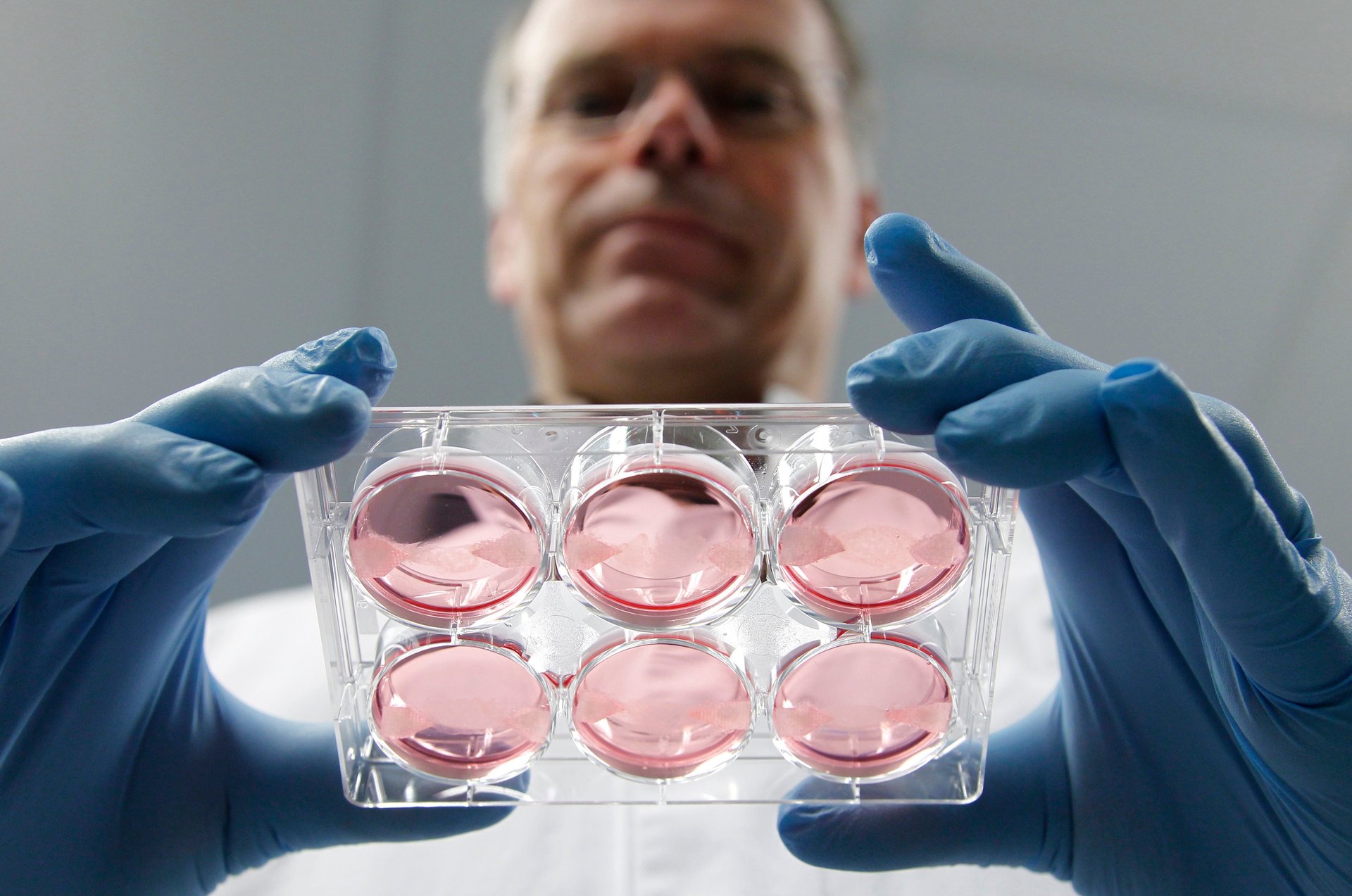

In vitro meat, which is also called lab-grown meat, test-tube meat, or cultured meat, has made a lot of headway in the past five years—and it’s not far off beginning to tempt the public palate. In 2013, Mark Post and his team at Maastricht University (bankrolled by Google cofounder Sergey Brin, no less) unveiled the world’s first lab-grown burger. For the first time in history, humans ate meat cultivated from stem cells in a laboratory, not from an animal killed in a slaughterhouse. The price tag was a whopping $325,000 per patty, but Post predicts that if he can scale his enterprise, he should be able to produce a pound of synthetic beef for about $30. (Beef prices reached an all-time high in 2014, but with the average price of a pound of ground beef in the US being about $4, he still has a ways to go.)

This success, as well as the tantalizing benefits of growing meat without animals, has led to a fresh crop of biotech food firms. Some of these include Memphis Meats, which has created the “world’s first cultured meatball” made from cells, and SuperMeat, an Israeli startup that is developing a way to use chicken tissue to grow meat. In the quest to provide “firm to table” food, other companies are working hard to create not just burgers, pork sausage, and steak bites but also cow-free cow’s milk and cheese.

Unlike in vitro meat laboratories, meat-producing facilities such as factory farms and slaughterhouses are far from humane, clean, or sterile. Pigs on factory farms are confined to cages so small that they can’t even turn around. Chickens are kept in huge, windowless sheds, and cows are crammed together by the thousands in mud- and feces-filled feedlots. In slaughterhouses, animals are often scalded to death in feather- or hair-removal tanks or have their throats cut while still alive and struggling.

E. coli, salmonella, and campylobacter thrive in the severely crowded conditions that animals are raised in, and mad cow disease can be linked to factory-farming practices. Animals are manipulated into producing unnatural amounts of flesh and milk, partly through antibiotics, the overuse of which is creating incredibly dangerous antibiotic-resistant bacteria. According to the United Nations, the meat industry is “one of the top two or three most significant contributors to the most serious environmental problems, at every scale from local to global” and is to blame for a large portion of worldwide greenhouse-gas emissions, deforestation, loss of biodiversity, and overconsumption of water.

And then there are the environmental benefits: According to scientists from Oxford University and the University of Amsterdam, lab-grown meat produces 96% fewer greenhouse-gas emissions, and its creation requires up to 99% less land, 96% less water, and 45% less energy than meat derived from live animals. In vitro products are also free of antibiotics and pathogens that could lead to pandemics.

A wide range of tasty mock meats already exists, offering the taste of meat without any of the cholesterol and cruelty. From soy “turkey” roasts and baked vegan “ham” to meat-free “beef” Wellington fit for a king, no one has to wait until Christmas future to enjoy delicious cruelty-free meals. But for people hooked on meat since childhood, in vitro meat will give them their meat fix without harming a single animal.

In vitro meat is no longer a question of whether this will be our future—but when.