Online surveillance will give Trump a lot of information on us. Here’s what you can do to resist

Donald Trump is about to have a lot of information on us. When he assumes the US presidency in a few weeks, he will oversee two separate but deeply interconnected surveillance apparatuses—which means that even Americans who typically take a blasé attitude toward privacy may be about to take it a lot more seriously.

Donald Trump is about to have a lot of information on us. When he assumes the US presidency in a few weeks, he will oversee two separate but deeply interconnected surveillance apparatuses—which means that even Americans who typically take a blasé attitude toward privacy may be about to take it a lot more seriously.

First, he will command the US intelligence community, including (but not limited to) the Central Intelligence Agency, the Federal Bureau of Investigation, and the National Security Agency. We really have no idea how much of our personal information will become available to him at this point. As Dana Priest and William Arken wrote in the Washington Post way back in 2010, this combined intelligence services of the US have “become so large, so unwieldy and so secretive that no one knows how much money it costs, how many people it employs, how many programs exist within it or exactly how many agencies do the same work.”

Second, as president, Trump will have influence over the distinct (but intersecting) surveillance system operated by corporate America. As algorithmic machine learning combines with increased online and offline data collection, corporations are increasingly adept at tracking our behavior—from our taste in sneakers to our sexual preferences, political allegiances, and spending patterns. In Europe, governments regulate to protect personal data, even enshrining individuals’ right to be forgotten by search engines. Current US governmental policy, by contrast, tends to treat the internet as the wild west.

We don’t yet know what the Trump administration will do with all this information, or how it will treat corporate surveillance. But even if you believe that the government and corporations use the information they glean from tracking only for benign goals (and you shouldn’t), surveillance is not a passive activity. The very fact of surveillance alters our behavior. More than that: it strips us of our humanity.

A panopticon for the 21st century

The panopticon is an instructive though imperfect metaphor for our present condition. Jeremy Bentham, the 18th- and 19th-century British utilitarian philosopher, first imagined the panopticon as a watchtower in the middle of a circular courtyard, surrounded by prison cells. The prisoners cannot see the guards in the central watchtower, but the guards can peer into the cells. Since the prisoners would never know when or if they were being watched, Bentham theorized, they would act as if they are being watched all the time.

Bentham was enthusiastic about the panopticon’s possibilities. “Morals reformed—” Bentham wrote of his planned building, “health preserved—industry invigorated—instruction diffused—public burthens lightened—Economy seated, as it were, upon a rock—the Gordian Knot of the poor-law not cut, but untied—all by a simple idea in Architecture!” Surveillance architecture as a solution to all of those ills: I see why so many exclamation points were needed.

French philosopher Michel Foucault later popularized the metaphor of the panopticon in his book Discipline and Punish. He explained that the panopticon’s applications extended far beyond prison—into hospitals, schools, and the workplace. “Among workers,” he wrote, “it makes it possible to note the aptitudes of each worker, compare the time he takes to perform a task, and if they are paid by the day, to calculate their wages.”

In today’s parlance: the panopticon scales. It is “a generalizable model of functioning,” Foucault wrote, “a way of defining power relations in terms of the everyday life of men.”

The physical panopticon never really caught on (though Wikipedia helpfully has a short list of buildings Bentham’s design inspired). But in the 21st century, we’ve become increasingly ensconced within a digital panopticon. We send emails for our observers to scan, write posts that they can parse, upload images that can be tagged and archived.

The metaphor isn’t perfect. The panopticon works by making visible the possibility of surveillance. But the government largely tries to hide the extent to which it scrutinizes us. Corporations, however, are less coy. Indeed, digital services increasingly rely on public displays of their knowledge. Digital assistants learn from the reams of data we provide it. Search engine results include emailed calendar items. Our maps guess about where we’re going next.

In both cases, surveillance is not conducted for its own sake. It is meant to modify our behavior. The government is looking for perceived threats to head off. Corporations are generally trying to get us to buy something we otherwise wouldn’t, or sell information to advertisers who share the same goal.

Corporations are scarier than hackers

To use conventional language, the panopticon threatens our privacy. But privacy is too small a word—or, rather, our conception of privacy is too limited. In the age of algorithms, of machine learning and big data, privacy means much more than our ability to control what others know about us.

When we talk about cybersecurity, we tend to focus on the idea of preventing human adversaries from gaining access to systems they shouldn’t. We want to keep hackers away from our emails, our bank accounts, our medical records.

That’s an important part of what it means to be safe online, but it is by no means the only piece. In fact, when we reduce cybersecurity to this one (important!) story, we are creating little more than a morality play, with easy protagonists and easier villains.

In this play, the government and behemoth information brokers like Google, Yahoo, and Facebook merely create the systems we use. Their primary responsibility to our safety is to encourage us to use strong passwords and enable two-factor authentication. The villains have Hollywood-worthy names: Fancy Bear, Guccifer, Anonymous. They are conveniently far away, and their motives are simple and straightforwardly evil. Privacy, when it’s thought of at all, is put in opposition to safety, not centered as a crucial part of it. But the reality of digital security is a good deal more complicated.

The messy truth is that those information brokers—that is, the corporations that build the internet—hold far more power than Anonymous or Fancy Bear to protect or harm us online. And their motives are not straightforwardly evil. They are driven, rather, by the same force that drives any business: greed.

We are all John Podesta

I have never met John Podesta, former secretary of state Hillary Clinton’s campaign chairman and consigliere. Nevertheless, I know how he makes his risotto. (Slowly.) I know what he thinks of Harvard law professor Lawrence Lessig (“Pompous.”) I know how he feels about the man who killed Cecil the lion (“What an asshole.”) I didn’t get these insights from Podesta’s Twitter feed, and he didn’t share them on a blog. Someone hacked him, and WikiLeaks spilled the contents of his inbox all across the web.

The leak is a crude reminder of something most internet users already know, but to which few of us devote enough thought. Email inboxes—and internet communication technologies in general—are more than mere repositories of correspondence. They are maps to both our digital and nondigital lives.

Users at 4chan, for example, combed through Podesta’s leaked emails for cell phone numbers, account data and other personal information, as Brian Mengus at Gizmodo reports. “With this information accessible to anyone with the time and energy to read through it all, users on 4chan’s /pol/ (politically incorrect) board were able to gain access to Podesta’s Twitter account, tweeting a message in support of Trump.” Apparently, WikiLeak’s Julian Assange was too busy tweeting conspiracy theories about Clinton’s health to responsibly remove details like phone, credit card, or social security numbers—or even details of a staffer’s suicide attempt.

Lubricated by convenience and ubiquity, email has wormed its way deep into our lives. For example, it is central to how I track finances; I receive alerts about big deposits and withdrawals, and log into my bank’s website with my email address. Health care, not immune to digitization creep, has started to incorporate email. Prescription refill notifications can be sent via email. So, too, can bills. My health care provider offers a “health coach,” a person I can email when I have questions. Beyond that, when I inevitably forget my 14-digit, multiple-non-alphanumeric-character passwords, email is how I recover them.

Email can even point the way to our devices. Our phones, those little computers we carry with us at all times, literally map to our physical worlds—something Podesta’s trolls discovered to their glee when they claimed to access his iCloud “Find my iPhone” feature.

Of course, internet communication is technically “safer” than ever thanks to encryption. But Podesta wasn’t vulnerable because his attackers broke through layers of encryption; this was a phishing attack. Tara Golshan at Vox lays it out: “In short, someone tricked Podesta into giving them his password, he didn’t have two-factor authentication set up as an additional check, and the campaign’s IT team led him astray.” Over at Motherboard, Lorenzo Franceschi-Bicchierai shows with fantastic detail how “Fancy Bear,” a group of Russian hackers who many believe have ties to the Russian government, uses this strategy often to target everyone from Podesta and Colin Powell to a range of journalists.

Some of these phishing attacks can be stopped by two-factor authentication, which requires that potential attackers have access to your phone and your inbox to get at your emails. But hackers can also use more technically sophisticated means to get at inboxes. Amid all the high-profile spy vs. spy news of recent months, Yahoo disclosed in September that hackers accessed information on 500 million accounts.

The point of all this isn’t to scare you into turning on two-factor authentication or using smarter passwords (though on both counts, you should). The point is that email contains more of our lives than we realize.

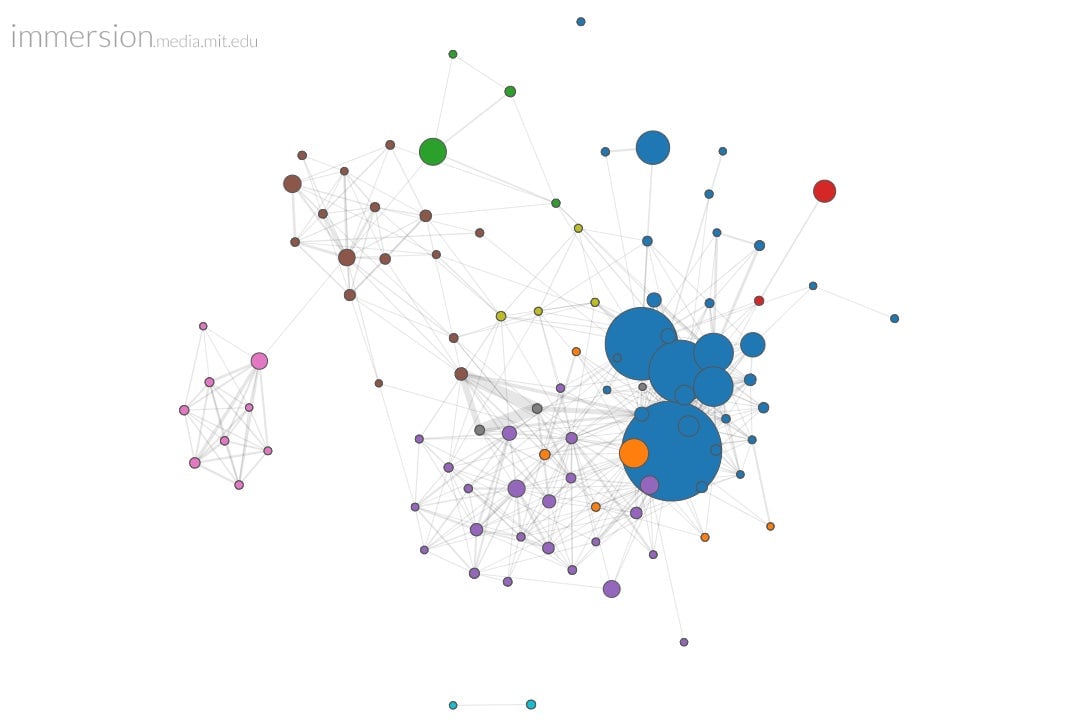

A few years ago, I stumbled onto Immersion, a project of the MIT Media Lab that visualized my email network—over 80,000 emails and 470 “collaborators.” I was stunned to discover how closely it mapped my offline reality—showing the closeness of some friends, the distance of others, the clusters of people I talk to about some things, and the clusters of people I talk to about others. You can even watch, by moving a slider, the network shift just as your relationships change.

Email—as content, metadata, and blueprint—is just one of many ways our digital lives shadow our offline ones. And the shadows we cast are of great interest to many people besides hackers.

What advertisers know about you

“I’m a knitter,” says Cathy O’Neil—mathematician, CEO of ORCAA, a firm that audits companies’ use of big data algorithms, and the author of Weapons of Math Destruction. “I’m actually, right now, looking at my computer, and I’m looking at this yarn on craftsy dot com.” O’Neil got there by clicking on an ad from Facebook. Tailored advertising—the kind that drove her to the yarn site—gives us “opportunities to buy things we like,” she tells me.

“The panopticon,” Foucault writes, is “a laboratory; it could be used as a machine to carry out experiments, to alter behavior, to train or correct individuals.” To understand how, exactly, the digital panopticon accomplishes this, we need to start at the beginning—with why we collect the data at all.

It starts with O’Neil’s yarn—with ads. If Facebook or Google or anyone else has enough data about our likes and dislikes, about our personalities, the algorithms they develop can “segment and silo us,” as O’Neil puts it. Any user of Spotify know that algorithms have gotten pretty good at identifying our individual tastes. This means algorithms can also modify our behavior. If left to my own devices, I would gladly listen to a dozen favorite albums on loop, but Spotify’s Discover Weekly playlist, tailored just for me, changes what I listen to. Similarly, the ads we see, constructed and targeted with us in mind, aim to modify our behavior by telling us: buy this product.

For many, O’Neil notes, tailored advertising “is a benign—if not positive—technology.” But that’s only true, she says, for the people who already have enough wealth, power, and privilege to avoid the dark side of tailored advertising.

O’Neil’s sharp-elbowed book, Weapons of Math Destruction, takes a hard look at the ways data, and the predictive models we plug data into, can wreak havoc and magnify the preexisting, dangerous hierarchies in our society. “We are ranked,” she writes, “categorized, and scored in hundreds of different models, on the basis of our revealed preferences and patterns.” Sometimes the ads that these insights inspire are from ethical—even sympathetic—companies: a yarn store targeting knitters. But the same technology used for these legitimate ads, she writes, “also fuels their predatory cousins: ads that pinpoint people in dire need and sell them false or overpriced promises. They find inequality and feast on it.”

Of the shady companies that make use of such data, including payday lenders, for-profit colleges are a particularly good case study. O’Neil writes that between 2004 and 2014, for-profit colleges tripled their enrollment. One such college, Vatterott, targeted—and this is from their own recruiting manual as revealed in a 2012 Senate committee report—“Welfare Mom w/Kids. Pregnant Ladies. Recent Divorce. Low Self-Esteem. Low Income Jobs. Experienced a Recent Death. Physically/Mentally Abused. Recent Incarceration. Drug Rehabilitation. Dead-End Jobs—No Future.”

Another for-profit institution, ITT Technical Institute, O’Neil writes, “went so far as to draw up an image of a dentist bearing down on a patient in agony, with the words, ‘Find out Where Their Pain Is.’”

For-profit colleges are already spending millions of dollars on Google advertising. With the full power of a user’s combined inbox, search terms, browsing pattern—and the inferred personality traits and histories that come with those data—it’s not hard to imagine that predatory industries will be finding more “pain points” to which they can apply pressure.

For-profit colleges do not help their students. As O’Neil writes, “diplomas from for-profit colleges were worth less in the workplace than those from community colleges and about the same as a high school diploma.” But “these colleges cost on average 20 percent more than flagship public universities.

The problem doesn’t stop with geographic- and personality-targeted ads. Even the prices you are quoted for a good or service can be changed based on the data that companies collect. ProPublica notes that internet users are being shown dramatically different prices for products based on ZIP codes. The authors highlight one discriminatory example, for an SAT prep course from the Princeton Review:

In Houston’s ZIP code 77072, with a relatively large Asian population, the Princeton Review course was offered for $7,200. While in Dallas’ ZIP code 75203, with almost no Asians, the course was offered for $6,600. And in heavily Asian, low-income Queens ZIP code 11355, the course was offered for $8,400.

ZIP code targeting and discrimination, though already being used to generate profits for companies, is a rough geography. What happens when corporations apply machine learning that can predict facets of our identities with greater accuracy?

Life in the fourth dimension

The impact of digital surveillance extends far beyond the digital realm, but at the same time it exists neither, exactly, here nor there. Surveillance is everywhere; it permeates. Then again, we’re everywhere, too.

“Where do our bodies begin and end in a networked world?” Laurence Scott asks in The Fourth-Dimensional Human, his slim book about what it means to be human in the internet age. This is less of a metaphor than you might think. He relates the story of a child who, after her weekly video call with her grandfather, hugs the iPad goodbye. “It’s strange to have your heart warmed and chilled in one go,” Scott notes.

Living our lives in the fourth dimension, the way we do now—physically in one place, but with a constant connection to anywhere our phone or computer projects us—makes us vulnerable to the prying eyes of these algorithms in the watchtower.

O’Neil writes that, more and more, companies—especially low-wage companies—are screening potential employees with personality tests. These tests aren’t simply measuring how “good” a worker you are (which would be sickeningly dystopian on its own). They are also potentially screening for mental illness—which is illegal and discriminatory.

According to a report in the Wall Street Journal, “The Equal Employment Opportunity commission is investigating whether personality tests discriminate against people with disabilities. As part of the investigation, officials are trying to determine if the tests shut out people suffering from mental illnesses such as depression or bipolar disorder, even if they have the right skills for the job, according to EEOC documents.” The authors note that “Rhode Island regulators said there was ‘probable cause’ to conclude that drugstore chain CVS Health Corp. might have violated a state law barring employers from eliciting information about the mental health or physical disabilities of job applicants.”

These personality tests are often based, they continue, “on a psychological model developed in the 1930s”

I can already hear the pitch: Why should you rely on self-reported data, which can be easily gamed, when specific patterns of online behavior, behavior we track, correlate to mental illness or “productive” work habits? This is the logical conclusion of big data algorithms: seemingly complete understanding, virtually complete surveillance, and the terrifyingly complete exercise of power.

Foucault says that the power of the panopticon is coercive. It forces us into binaries: sick/well, productive/slovenly, normal/abnormal. We stand on the precipice of algorithmic clarity, where these corporations’ machines could—and almost certainly would, if the monetary incentives were present—dictate the shape of our lives. When our online behavior doesn’t match what algorithms expect, we are an outlier—abnormal. When our patterns fit a given profile, we are only shown what the algorithms expect us to want. As we’ve seen with so-called personality tests and tailored advertising, algorithmic bucketing can cost us jobs and livelihood. What else can it cost us?

This is the panoptic present. And even if it doesn’t cost us our jobs or our freedom, the upshot of living in the constant gaze of machines is that the world begins to see us—human beings—as predictable data.

Here, the digital panopticon is at its most insidious. It splits us, assigns us a score, and the world we inhabit is irrevocably altered because of it. The algorithm shows me the things it thinks I—or others like me—ought to be shown; I am not shown the world as it really is. In this way, panopticism is self-reinforcing: as I am shown more of what I am supposed to like, I grow to like the things I am supposed to.

The insights machines glean are blinkered to the messy, human truth of our existence. To use unfashionable language, they do not understand souls. That this language is unfashionable is its own problem, but it is also a symptom of panopticism’s disease.

“Interesting philosophy is rarely an examination of the pros and cons of a thesis,” Richard Rorty writes in Contingency, Irony, and Solidarity. “Usually it is, implicitly or explicitly, a contest between an entrenched vocabulary which has become a nuisance and a half-formed new vocabulary which vaguely promises great things.”

The language of the panopticon has become a nuisance—at least if you wish to live in a world that has a place for a soul. There is no room for soul with the small-minded behaviorists who tell us our online actions can predict all that is useful to know. In the grip of this language—overflowing with progress and innovation, efficiency and prediction—a person is the sum of her quantifiable actions. Her soul a thing to be scoffed at or ignored.

But we are not doomed to this future. The 21st-century panopticon only works because we power it with our data. Our: This word implies ownership. Personal data is something that we own. Our technology prompts us to give it away—by hook or by crook, by the promise of convenience or by the crude club of coercion. And the more we focus exclusively on the possibilities offered by technology and disruption, the more likely we are to shrug off concerns about what we are giving up in the process.

The language we use determines what we are capable of imagining. So I am not surprised that we have imagined progress so narrowly that it is reducible down to the speed with which a machine can predict our desires. To reclaim a world habitable by souls, we need first to speak of them.

The concept of herd immunity is useful here. Algorithms like the ones that power the panopticon require scale to work. That is, for “birds of a feather” analysis to work, they need a large corpus of behaviors to sift through. Just as there are those whose immune systems are compromised and cannot be vaccinated, there are those on the margins who cannot help but be scrutinized—the victims of predatory industries who lack the time and resources to defend themselves. It is up to the rest of us to protect them by taking the inoculation.

I like efficiency as much as the next person. But I can stand a little less of it in my life, a little less convenience. If you can, too, then the way forward is clear: starve the beast. Make our data ours again. Push for regulations. Use apps like Signal, which allows you to send encrypted messages. Turn on your adblocker. Lie on online forms. And begin engaging with the old-fashioned language of souls—literature and art and music and poetry. Not all human endeavors are efficient or convenient. They nourish us for that very reason. If we want to fight the panopticon, we have to remember the wide-open world that lies beyond its walls.