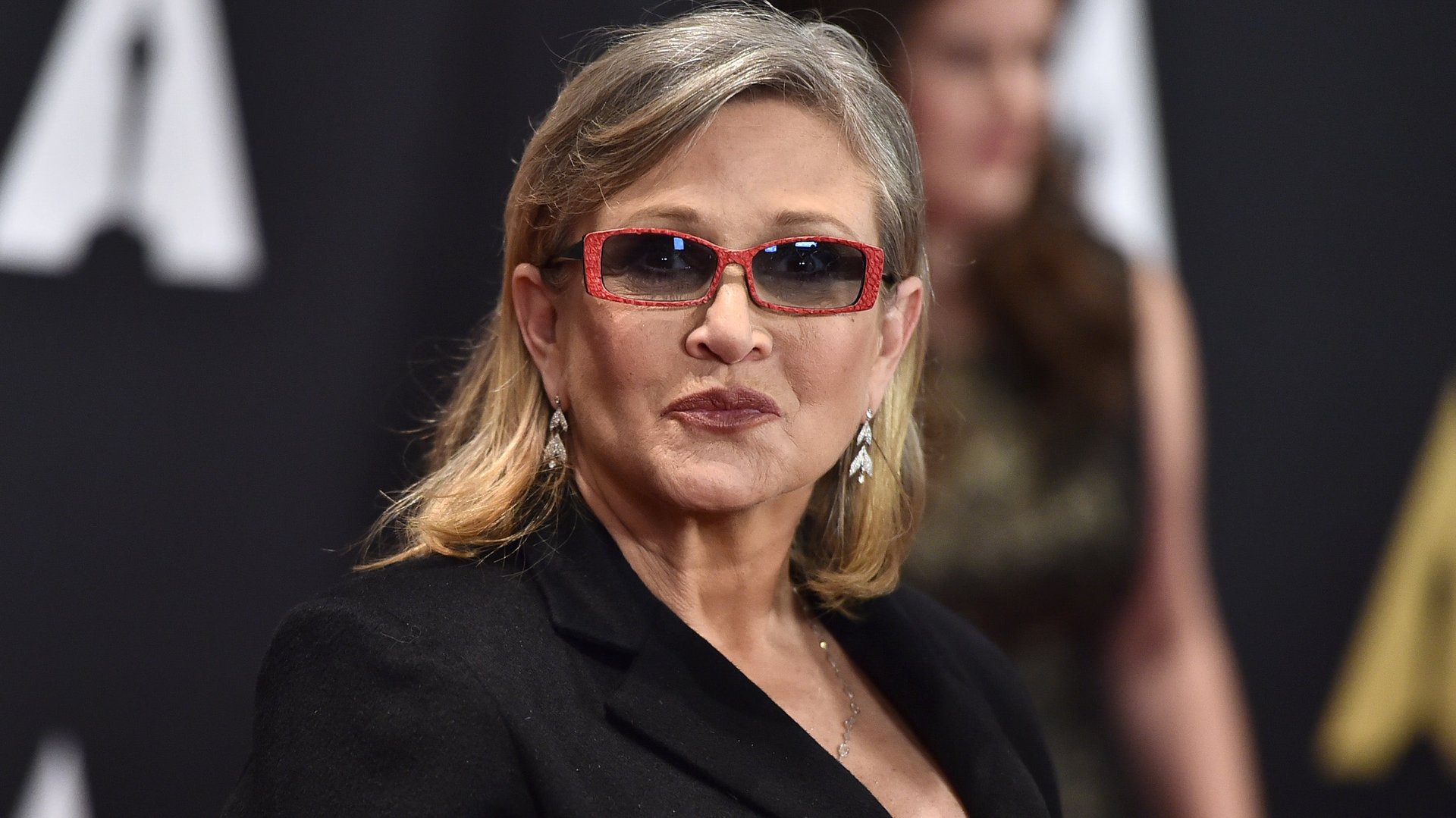

Carrie Fisher’s most feminist act was her frankness about being bipolar in a world where women are called “crazy”

Carrie Fisher could have made things easy on herself. As the obituaries roll in this week, and slave-bikini photos and “Goodbye, Princess Leia” headlines fill social-media feeds, it’s important to remember: Her role as the young, beautiful heroine in a hit film could have been her only legacy. She could have shined as a starlet, then chosen to quietly fade away.

Carrie Fisher could have made things easy on herself. As the obituaries roll in this week, and slave-bikini photos and “Goodbye, Princess Leia” headlines fill social-media feeds, it’s important to remember: Her role as the young, beautiful heroine in a hit film could have been her only legacy. She could have shined as a starlet, then chosen to quietly fade away.

But that wasn’t Fisher’s style. In fact, she refused to fit any of the stereotypical and limiting roles that the world tried to force upon her: Hollywood heiress, bimbo in a bikini, drug-addled trainwreck, crazy showbiz reject, washed-up old lady. She managed to reclaim her own narrative by relentlessly confronting the world with the spectacle of her human complexity. And Fisher’s heroic shamelessness—the fact that she never toned it down, never apologized for taking up space, never repented for the sin of being a flawed, human woman in the public eye—was never more evident, or more admirable, than in her advocacy for people with mental illness.

Fisher was first diagnosed with bipolar disorder in her 20s, after a drug overdose that nearly killed her. She wasn’t alone: Around 60% of people with bipolar disorder have abused drugs or alcohol at some point, often because they’re instinctively attempting to stabilize their mood swings.

“Drugs made me feel more normal … they contained me,” Fisher said of that time. At the peak of her addiction, she was taking 30 Percadin a day. Still, when the doctors told her a treatable mental illness undergirded her drug problem, she initially refused to believe it: “I thought they told me I was manic depressive to make me feel better about being a drug addict,” she told Diane Sawyer in 2000.

Any actress dealing with all this—addiction, disgrace, near-death, nervous breakdown—would be forgiven for trying to hide it. Many people with mental illness feel ashamed of their diagnosis. Society encourages them to try to keep it quiet—to sweep their suffering under the carpet and hope that no one finds out.

Then there was the Fisher option. Upon her release from rehab, she immediately threw a huge party, featuring a rented ambulance and a cardboard cut-out of Princess Leia strapped to a gurney with an IV in her arm. Her novel based on the experience, Postcards from the Edge, came out a few years later, in 1987.

It took Fisher years to fully accept her diagnosis—another common reaction to bipolar disorder, which is easy to deny simply because the symptoms can disappear for long periods of time. But once she did accept, she barreled into it with a spirit of gleeful candor—thereby doing an enormous public service for everyone who’s ever dealt with mental health issues.

Fisher didn’t just talk about taking medication; she told interviewers how many medications she took per day, let them look through her pill organizer, and crafted zingers about side effects. (On weight gain: “Yes, in answer to your unexpressed question, sanity does turn out to come at a heavy price.”) According to one profile, the tiles in her kitchen floor were “shaped and labeled like enormous tablets of Prozac.”

She didn’t just talk about getting shock treatment; she titled her 2011 memoir Shockaholic, and gave interviews praising the horror-movie staple for helping her recover from a depressive phase. (“It’s very easy and very effective,” she told Rolling Stone. “And it’s not used as punishment by nurses in a mental hospital when you’re bad, which is how it’s depicted in literally every movie.”)

Not everyone could do what Fisher did. Not everyone should: She was witty, charming, and so well-off she didn’t actually need to work, which made the social and professional stigma of mental illness far less dangerous in her case. But impossible to overstate how meaningful it was for people with mental illness to have an advocate like Fisher. She never downplayed how painful bipolar disorder can be—“your bones burn,” she once memorably said of mania. But she also refused to portray it as an unending tragedy. She insisted that bipolar people were, above all, human: “Generally someone who has bipolar doesn’t have just bipolar, they have bipolar, and they have a life and a job and a kid and a hat and parents,” she said. “So it’s not your overriding identity, it’s just something that you have, but not the only thing–even if it’s quite a big thing.”

Talking about mental illness in such a frank way was a brave act, particularly for a woman who admitted to being intensely sensitive to media criticism. To be a woman is to live with the perpetual threat of being called crazy. But to be a woman with actual mental illness is something else again: No matter who you are, no matter what you do, the world treats you as a worst-case scenario and a dirty joke, someone who has failed at being female. Fisher was open about the fact that she took ownership of her story in part to defuse the uglier, crueler stories that surfaced regardless. “Things come out [in the media] about me,” she said. “When it’s out, it’s someone else’s version of what’s the matter with me. I want it to be my version of what it is. My recourse is to do my version.”

But she made that bravery look effortless, and that was what mattered. Even when facing an illness practically defined by shame, a diagnosis so stigmatized that people who own up to the illness are seen as monsters and freak shows rather than human beings, Carrie Fisher was able to defuse the stereotypes aimed her way simply by talking back to them; by shouting, as loudly and cheerfully as possible, that she had it, she didn’t care if you knew it, and by the way, here was this one hilarious thing she did the last time she was manic. For other women living with bipolar—of which I am one, having been diagnosed with bipolar II in the summer of 2012—she was a sign that we weren’t alone. So no matter how worthless or freakish or doomed other people said we were, it couldn’t be all that true. If we were shameful, then so was goddamn Princess Leia—and everyone loved Princess Leia.

Fisher never had to do any of it. Her performance as Princess Leia would have secured her a legacy all on its own. But by peeling back the edifice of her glamour and insisting we meet the messy, funny, flawed woman underneath, Carrie Fisher became her own legend.