There’s a vital organ in your gut you didn’t know you had

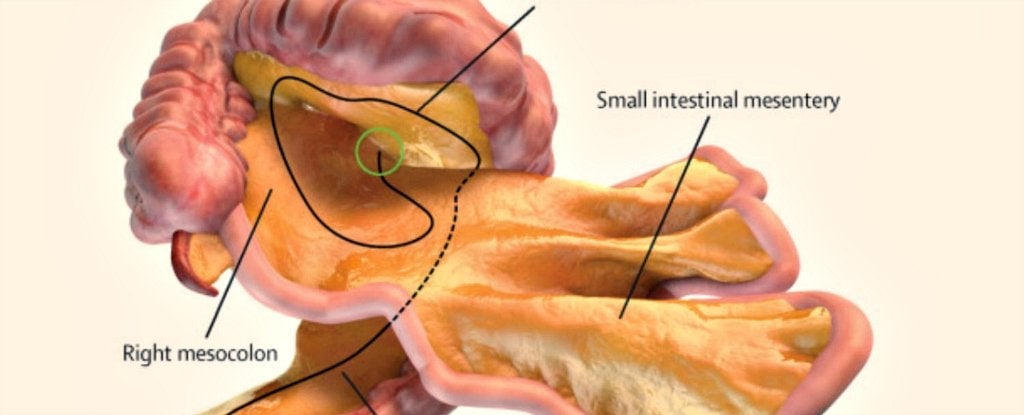

Tucked behind the skin of your belly and your abdominal muscles is a hidden structure that carries out a vital role: your mesentery.

Tucked behind the skin of your belly and your abdominal muscles is a hidden structure that carries out a vital role: your mesentery.

“It keeps the intestine in a particular shape,” says J. Calvin Coffey, a general and colorectal surgeon at the University of Limerick in Ireland. That way, “when you stand up, [your intestine] doesn’t fall into your pelvis.”

This may not sound like a massive feat, but from a physiological standpoint, it’s crucial. In biology, structure closely follows function. The small intestine squeezes liquified foods through the entirety of its 22 feet (6.7 meters) like a tube of toothpaste to mix meals with enzymes that extract nutrients to be shuttled all over the body; without your mesentery, which holds your intestines in place along your abdominal wall, your intestines run the risk of getting tangled in the blood vessels that supply it with energy. Children born without a mesentery, Coffey says, can suffer “catastrophic events” when their intestines are suffocated.

On Jan. 3, Coffey and colleague D. Peter O’Leary, also a general surgeon, published (paywall) a review in Lancet Gastroenterology and Hepatology proposing that this structure is so well-defined and important, it should be considered its own organ, as opposed to a type of crimped tissue, called peritoneum, which is dispersed throughout the abdominal cavity.

The discovery of the mesentery is not new; in fact, even da Vinci noted it in his anatomical drawings in the 1400s (though he did didn’t get the shape quite right). The mesentery continued to pop up in textbooks through the the 1800s and modern medicine—sort of. Most scientists thought what we now know as the mesentery to be unconnected sections of tissue scattered throughout the intestines.

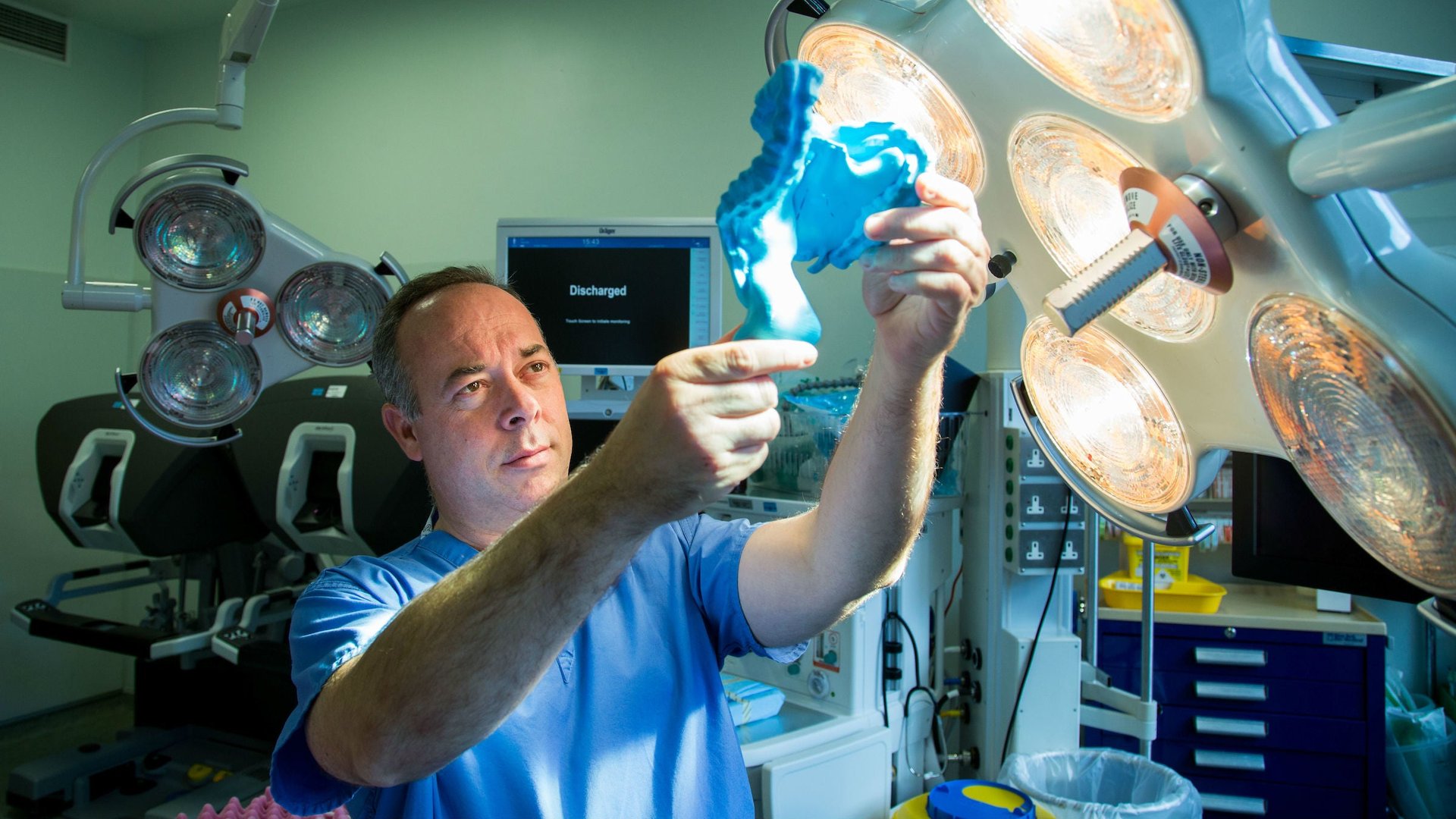

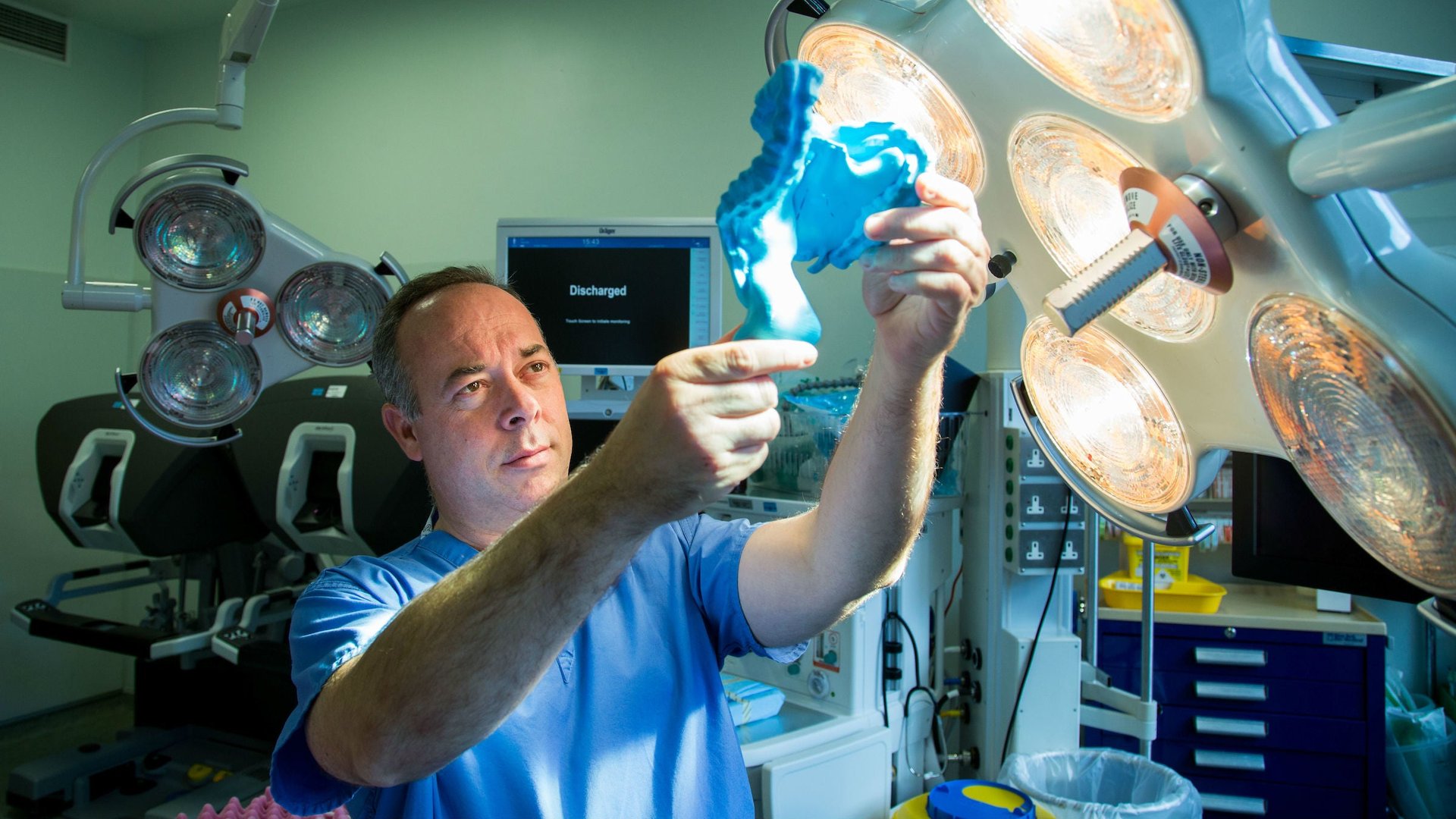

In 2012, Coffey and a team of colleagues identified that it was, in fact, a continual structure by peeling away layers of cells in the gut. For four years, they’ve continued to research the mesentery (as have other scientists around the globe) until they gathered enough information to propose that it be considered an organ.

Currently, there are 78 organs that make up 13 systems in the human body as defined by the Federative International Programme on Anatomical Terminologies (FIPAT), an international group based in Switzerland that keeps tab on all 7,500 body parts—all of which you can read through here (pdf).

Organs are typically classified by either their specific structure or a clear function. For example, “the stomach, bladder, and kidneys are all self-contained areas of tissues that all work together to have one function,” says Jennifer Whitney, a physiologist at Georgetown University. So despite the fact they they have one function, they are each organs because they have discrete structures. On the other hand, substances like blood are also sometimes considered an organ because, although blood circulates throughout the body and has no specific structure, it has a unified function: to bring oxygen to other organs and circulates immune cells. And although the appendix doesn’t have a specific function (that we know of), it’s still considered an organ because the condition caused by its infection, known as appendicitis, affects about 5% of people.

The mesentery, Coffey argues, should be considered an organ because it holds up our intestines (a discrete role) and has a distinct structure. “It has a beginning and an end, and in between it kind of fans out like a Chinese fan,” he says, and is usually about two feet long.

There’s no real benefit to defining the mesentery as a separate organ. Students may be introduced to it sooner in biology classes, Whitney explained, but other than that, “it doesn’t really matter.” Coffey, though, thinks that by defining the mesentery more concretely, it would be easier to standardize information about it, which could be used for improving abdominal surgery techniques.

The FIPAT did not respond to comment about the mesentery at the time of article publication.