Women are making a powerful point about sexual violence by displaying the clothes they were assaulted in

After a recent New Year’s Eve celebration in Bengaluru, India, turned into what eyewitnesses called a “mass molestation” of women, a few politicians came forward with a culprit for the reported assaults: “They try to copy westerners not only in mindset, but even the dressing,” said Bengaluru home minister G. Parameshwara, “so some disturbance, some girls are harassed, these kind of things do happen.”

After a recent New Year’s Eve celebration in Bengaluru, India, turned into what eyewitnesses called a “mass molestation” of women, a few politicians came forward with a culprit for the reported assaults: “They try to copy westerners not only in mindset, but even the dressing,” said Bengaluru home minister G. Parameshwara, “so some disturbance, some girls are harassed, these kind of things do happen.”

“Women call nudity ‘fashion,’” said Abu Azmi, a leader of the Samajwadi party, explaining why the assaults were bound to occur.

Many decried the comments, but they are hardly isolated cases. Far too often, in India and elsewhere, women are blamed for the harassment and violence they suffer because of their clothes, despite the overwhelming evidence that men, not skirts, are responsible. “Nonsense” is what Jasmeen Patheja calls the notion that a woman’s outfit prompts sexual harassment. In 2003, Patheja launched an activist group called Blank Noise to fight street harassment of women, and which has now embarked on a project that’s making this point about 10,000 times over.

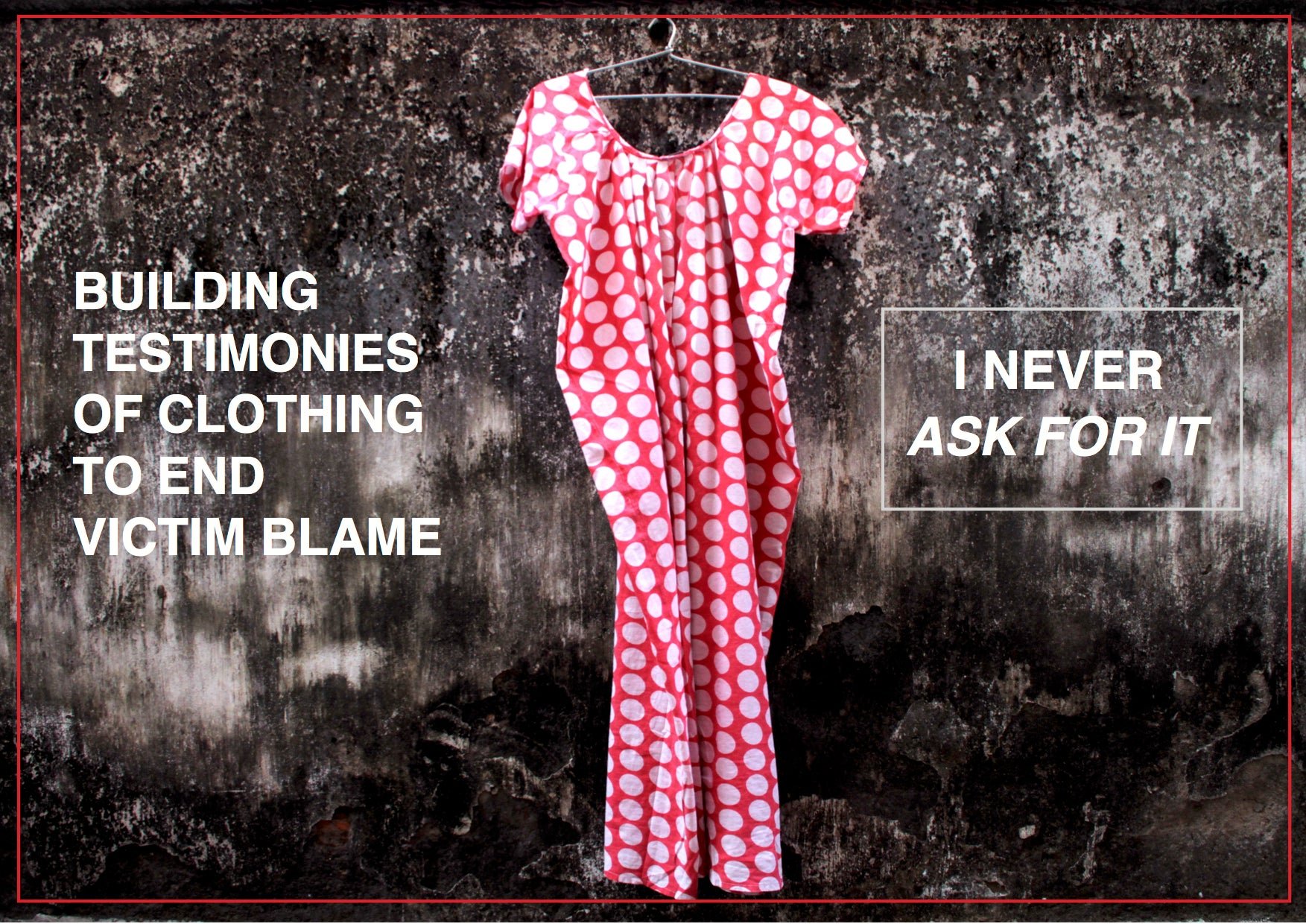

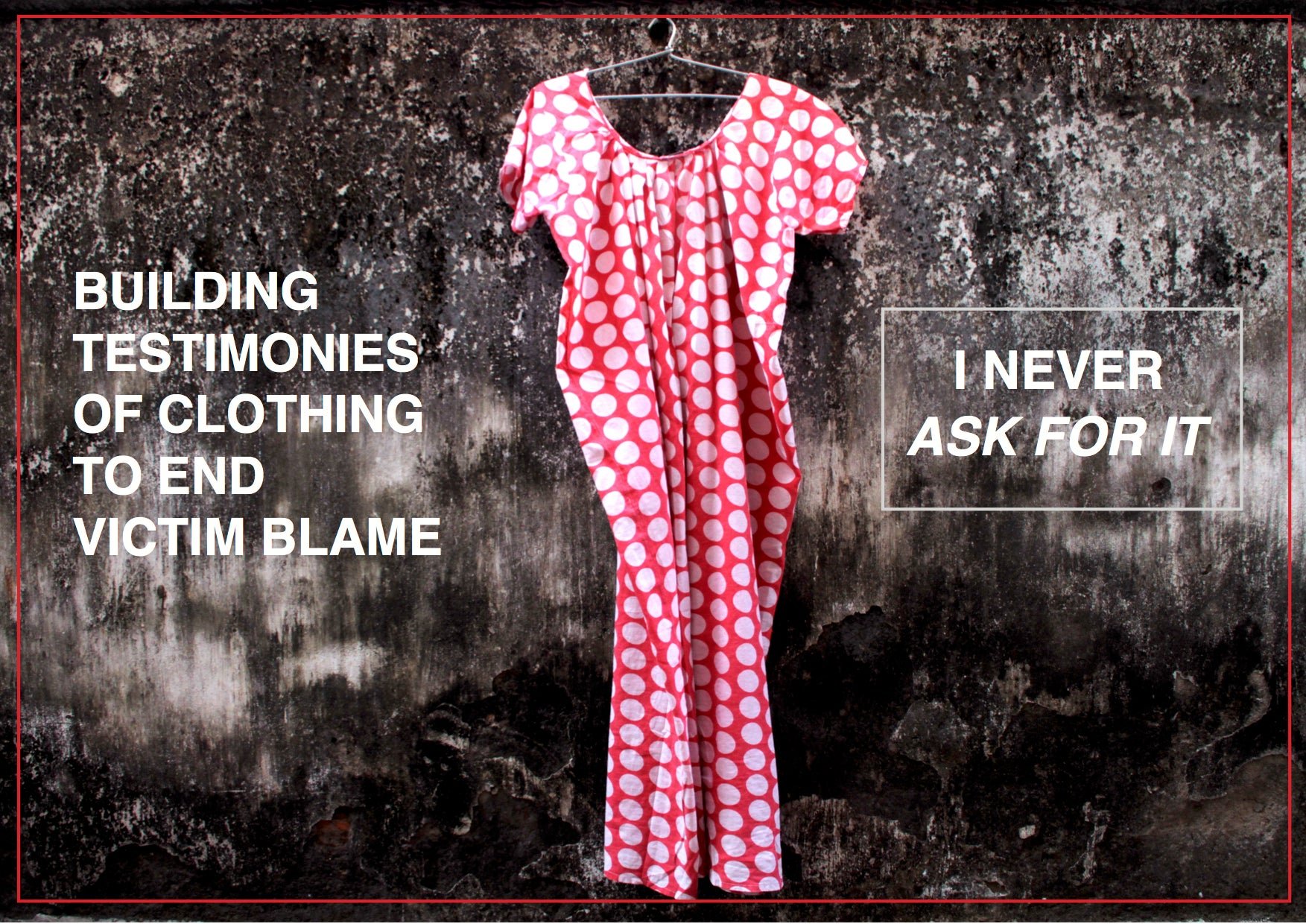

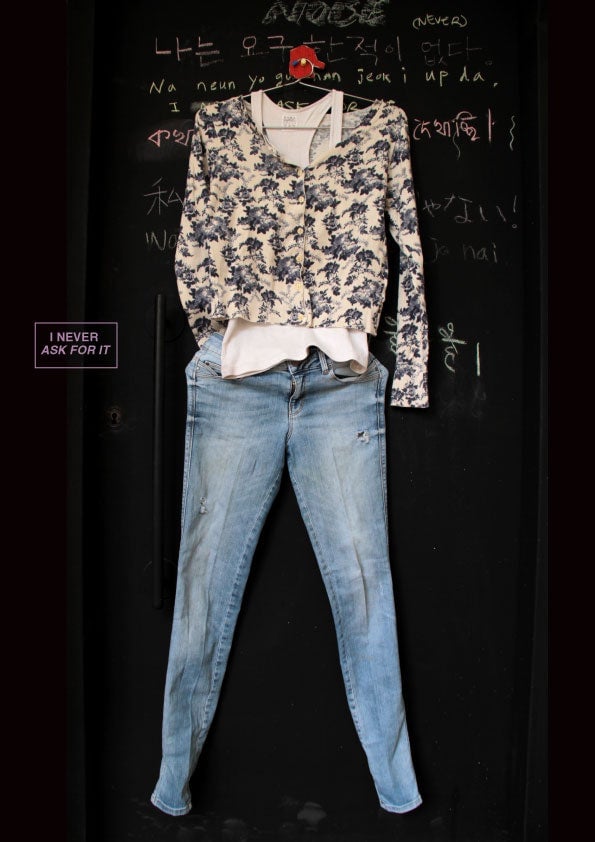

The Bengaluru-based group is collecting and displaying garments that women were wearing at the time they were sexually harassed or assaulted. The project, called “I Never Ask For It,” aims to ultimately exhibit 10,000 pieces, potentially in different cities around the world.

While it’s likely to take several years to gather all the garments planned, more than 200 women have already stepped forward and sent Patheja their clothes. The images of these garments that Blank Noise has posted online make clear what a woman is wearing does not determine whether she’s targeted: In clothes of all sorts, the contributors were shouted at, groped, or otherwise harassed.

Yet there continue to be those who argue that women share the blame because of their choice of outfit, and not just in India. Amnesty International once found that a quarter of Britons surveyed in a poll believed the woman was at least partly to blame for being raped if she was wearing sexy or revealing clothes.

Besides deflecting blame from those who deserve it, these beliefs can lead women to falsely thinking they’re at fault. ”If you’re constantly being told and raised as a girl to be careful, when you experience violence the link usually is, ‘Maybe you weren’t being careful enough,'” Patheja explains. “Blame is internalized.”

The clothes in “I Never Ask For It” are a visible symbol of this process. Patheja got the idea more than a decade ago, while reading of women’s experiences of harassment and violence from around the world, including the US and UK. She noticed that women, regardless of where they were, often described the clothes they were wearing.

Blank Noise has been in touch with activist groups in countries beyond India, and they hope women from all over will contribute to what Patheja calls a global dialog on victim blaming—a problem she says is made much worse when public figures use this line of argument. She points to comments by officials, including US president-elect Donald Trump, who was heard saying women let you grope them “when you’re a star” in a 2005 tape that surfaced during the recent election campaign.

“Every time somebody in a position of power is making a statement that justifies violence against women and sexual-agenda based violence through a process of victim blaming, they are enabling a certain kind of behavior,” she says. “They’re excusing violence.”