Fifty years frozen: The world’s first cryonically preserved human’s disturbing journey to immortality

“Yes, Mr. Bedford is here.” That’s what Marji Klima, executive assistant at the Alcor Life Extension Foundation in Scottsdale, Arizona, told me over email

“Yes, Mr. Bedford is here.”

Suggested Reading

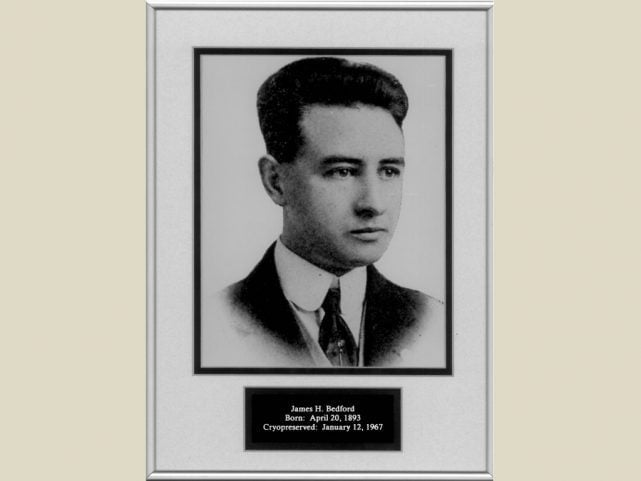

That’s what Marji Klima, executive assistant at the Alcor Life Extension Foundation in Scottsdale, Arizona, told me over email this week. She was referring to Dr. James Hiram Bedford, a former University of California-Berkeley psychology professor who died of renal cancer on Jan. 12, 1967. Bedford was the first human to be cryonically preserved—that is, frozen and stored indefinitely in the hopes that technology to revive him will one day exist. He’s been at Alcor since 1991.

Related Content

His was the first of 300 bodies and brains currently preserved in the world’s three known commercial cryonics facilities: Alcor; the Cryonics Institute in Clinton Township, Michigan; and KrioRus near Moscow. Another 3,000 people still living have arranged to join them upon what cryonicists call “deanimation.” In other words, death.

Cryonics patients are no longer frozen, but “vitrified.” First, the body is placed in an ice-water bath. Then, ice-resistant chemicals are pumped into the body, taking the place of water in the blood. That way, in the next step, when the body or brain is cooled to well-below freezing using nitrogen gas, it hardens without forming cell-damaging ice.

Vitrification has been used to effectively preserve blood, stem cells, and semen. But restoring life to a vitrified human—or to an organ as complex as the brain—remains an unfathomably distant prospect. If there is a divide on cryonics in the scientific community, it’s between neuroscientists willing to state that reanimation is at least within the realm of physical possibility, and those who believe it’s so unlikely that selling even the hope is unethical.

“[R]eanimation…is an abjectly false hope that is beyond the promise of technology and is certainly impossible with the frozen, dead tissue offered by the ‘cryonics’ industry,” McGill University neuroscientist Michael Hendricks wrote in MIT Technology Review.

Bedford’s preservation in the pre-vitrification days was a crude, ad hoc affair. He legally died in a southern California nursing home at the age of 73, after donating his body to the Life Extension Society, a group of early cryonics enthusiasts. Hours after death he was injected with the solvent dimethyl sulfoxide in an attempt to stave off tissue damage, packed in a Styrofoam box of dry ice, and eventually submerged in liquid nitrogen.

For the next 27 years, Bedford’s liquid-nitrogen-filled chamber was constantly on the move, as various cryonics companies folded or were forced to move for insurance or regulatory problems. The $100,000 he’d set aside to pay for his body’s long-term care evaporated as his wife and son faced legal challenges from other family members objecting to his unconventional resting place. From 1977 to 1982, frustrated with the high cost of maintenance, they appear to have kept his unit in a self-storage facility in southern California, occasionally topping off the liquid nitrogen themselves.

Upon his wife’s death in 1982, Bedford’s body and container were entrusted to the company that became Alcor. Then-director Jerry Leaf, who died and was cryopreserved in 1991, took out a life insurance policy on himself to fund Bedford’s ongoing care.

Bedford has been seen only once in the last 50 years. In 1991, Alcor moved him from his failing unit to a new storage tank. A report detailing the procedure makes for grim reading. The skin on his neck and upper torso was inflamed. His nose had collapsed. His chest had cracked.

To Alcor personnel fearing far worse damage to a man revered as a pioneer, he was beautiful.

“I cannot describe the feeling of elation I had when I peeled back the sleeping bag that enclosed you and saw that you appeared intact and well cared for,” former Alcor president Mike Darwin wrote in an open letter to Bedford, to be read in the event of his return. “Whatever else has happened, you have remained frozen all these years.”