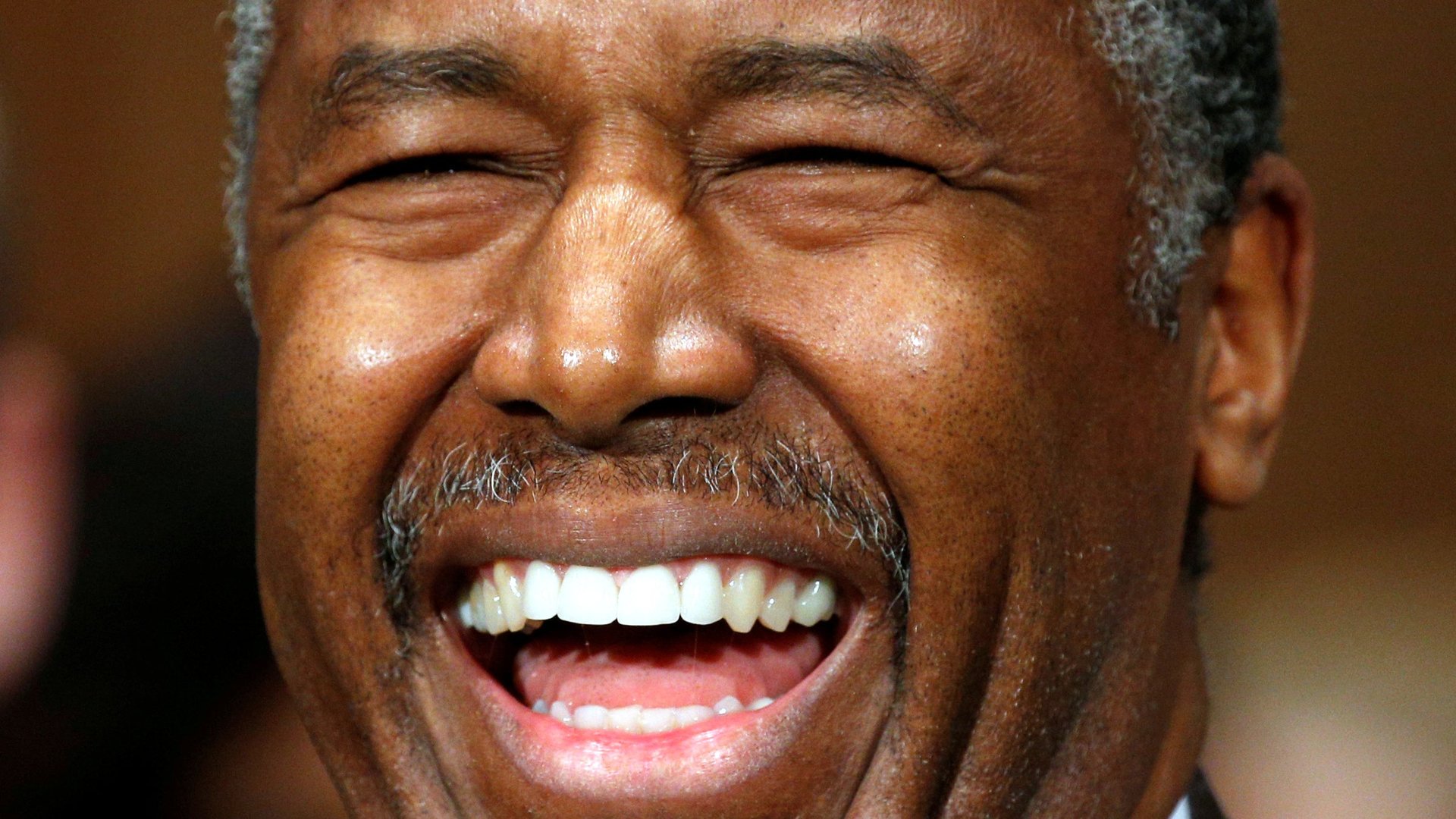

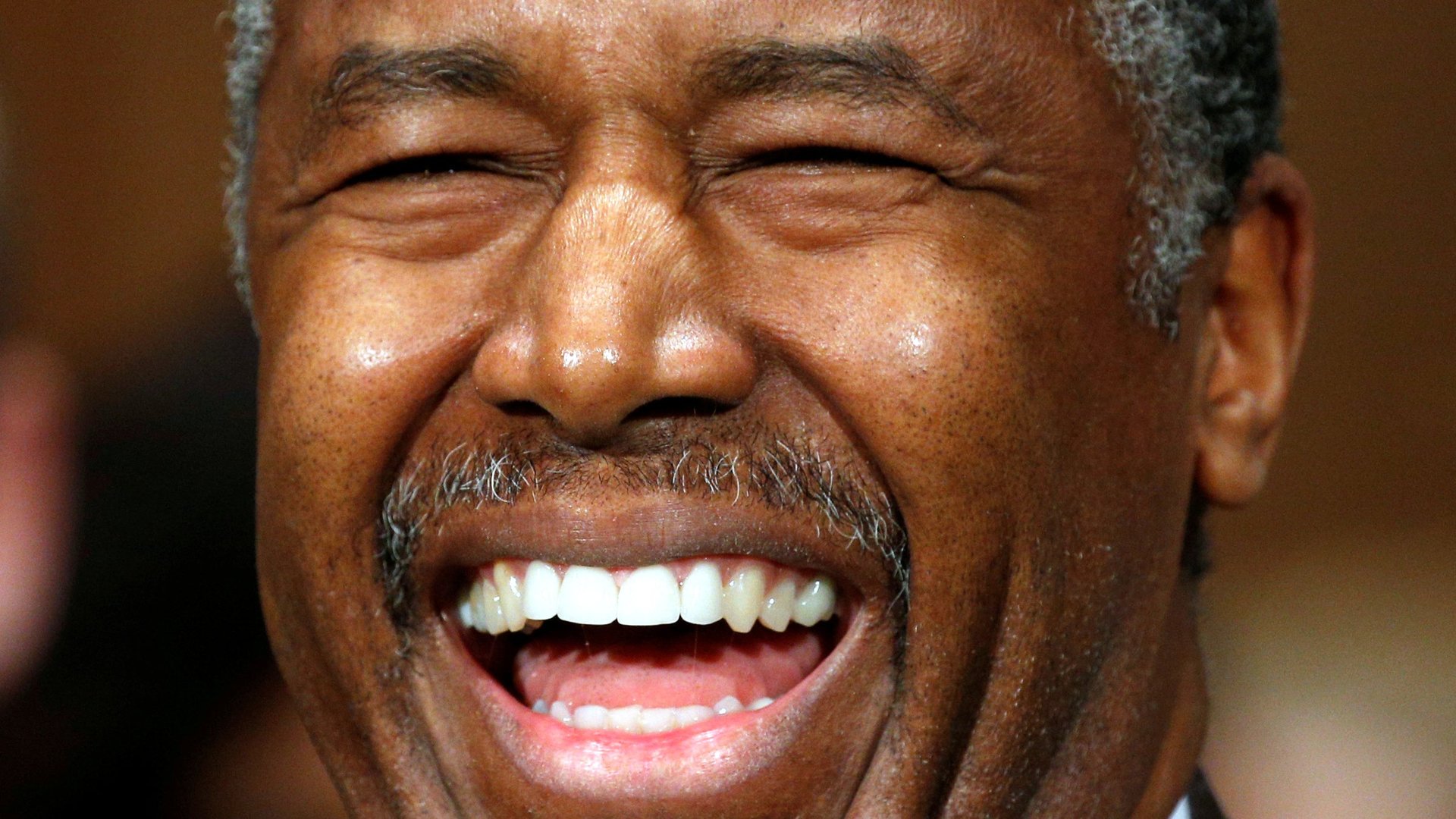

Ben Carson doesn’t seem to understand America’s 30-year, fixed-rate mortgage. Do you?

One of the unique aspects of the United States is that banks lend people great sums of money at fixed rates for 30 years in order to buy a house.

One of the unique aspects of the United States is that banks lend people great sums of money at fixed rates for 30 years in order to buy a house.

Ben Carson, physician and politician, has been tapped by president-elect Donald Trump to manage the Department of Housing and Urban Development. HUD is responsible, at least in name, for this uniquely American bit of financial engineering, which relies on the government guaranteeing loans made by private institutions.

At his confirmation hearing today, Carson was asked about this financial product by Senator Jon Tester of Montana. Did Carson think that a 30-year, fixed-rate mortgage loan would be widely available without government backing?

“Yes, I think it is possible,” Carson said.

“How ya going to do it?” the senator replied.

“The private sector,” Carson said. “But you can’t do it overnight.”

This belies the entire history of the 30-year, fixed-rate mortgage. Many experts say the private sector simply cannot deliver the same benefits without government backing. Here’s a refresher course: In the throes of the New Deal, the US government birthed a plan to promote home ownership by creating a mortgage market backed by the Federal Housing Administration, or FHA, which lives within HUD. The FHA would combine with banks to insure long-term, fixed-rate mortgage loans in an effort to replace the shorter-term, variable-rate loans available to home buyers at the time. This helped boost the US economy after the Great Depression and allowed many more people to buy homes.

Over the decades ahead, the government expanded on this idea by creating Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, two major financial institutions that back 30-year loans by purchasing them from banks and securitizing them into mortgage bonds. Laws allowing Americans to deduct mortgage interest from their taxes also boosted affordability.

Such government support ensures wide availability of long term, fixed-rate home loans. They have become a political sacred cow in a society that sees homeownership as a key component in the American dream. And there are good arguments that the 30-year, fixed-rate mortgage creates financial stability more effectively than the short-term loans that blew up the economy in 2008.

It would be one thing if Carson recognized that the 30-year mortgage wouldn’t be widely available without government backing and instead argued that a different model is needed. Developed countries like Germany, for example, get by happily with lower homeownership rates and no 30-year loans. Critics are quick to note that Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac had to be rescued by the government during the 2008 collapse of the housing market, though they eventually paid back that cost. Libertarian-leaning commentators argue that the housing market should be left to its own devices, with private lenders only making loans of at the rates and terms of their choosing.

Many point to the private market for “jumbo” home loans—those that are too big for government backing—for homes above a ceiling ranging from $417,000 to $625,000, depending on local conditions. Its existence suggests that, if the sum is large enough, banks are willing to take a risk on a long-term loan. But more modest homebuyers will struggle. Even the most bullish advocates of private mortgage markets think the interest rates on 30-year mortgages would rise at least one percentage point absent government backing, while market participants expect three percentage points or more. That would add hundreds of dollars to the average monthly mortgage payment, at a time when interest rates are already expected to rise.

But Carson wants to preserve a financial instrument dependent on government backing while promising something that most experts say the private sector can’t deliver. The good news, such as it is, is that schemes to change the all-important housing finance market will be led at higher levels, with the Treasury Secretary—who is responsible for Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac—taking charge. The man tapped by Trump there, former Goldman Sachs partner Steve Mnuchin, has already floated plans to privatize the two big government-backed housing lenders.

Without details, it’s hard to know if Mnuchin’s plan would protect or imperil the 30-year, fixed-rate mortgage. But we hope he, at least, knows where it came from.