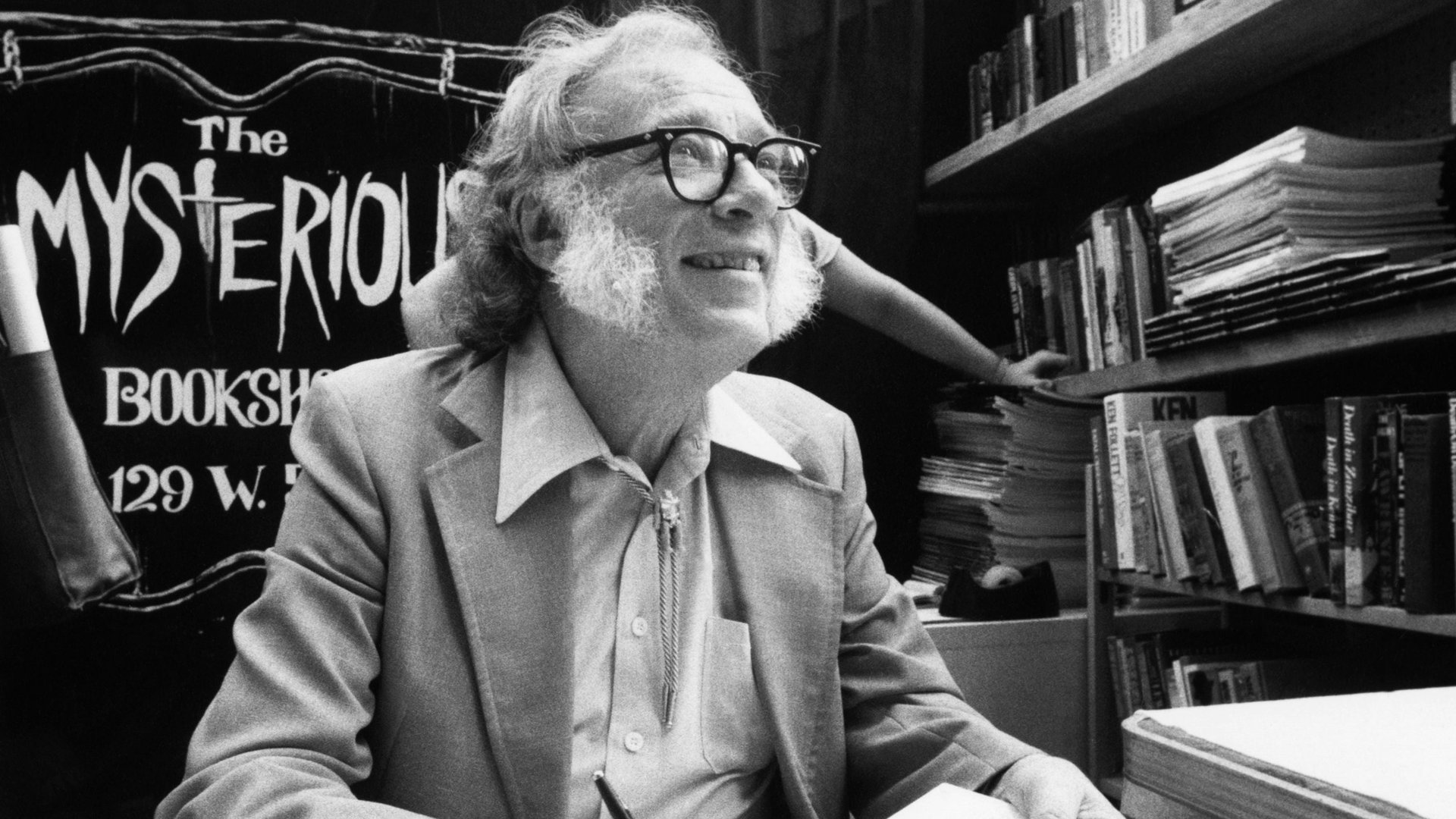

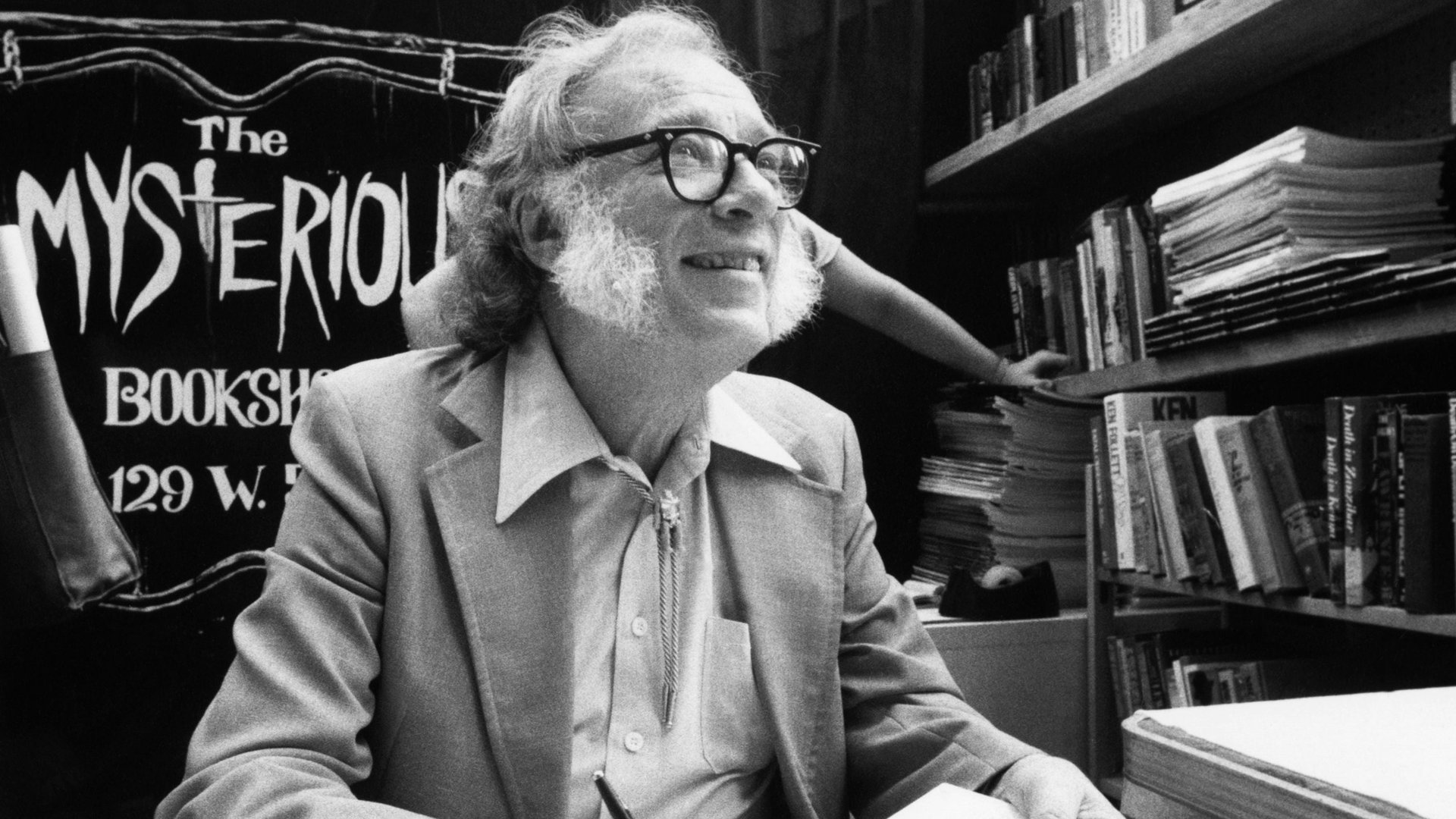

Isaac Asimov wrote almost 500 books in his lifetime—these are the six ways he did it

If there’s one word to describe Isaac Asimov, it’s “prolific.”

If there’s one word to describe Isaac Asimov, it’s “prolific.”

To match the number of novels, letters, essays, and other scribblings Asimov produced in his lifetime, you would have to write a full-length novel every two weeks for 25 years.

Why was Asimov able to have so many good ideas when the rest of us seem to only have one or two in a lifetime? To find out, I looked into Asimov’s autobiography, It’s Been a Good Life.

Asimov wasn’t born writing eight hours a day, seven days a week. He tore up pages, he got frustrated, and he failed over and over and over again. In his autobiography, Asimov shares the tactics and strategies he developed to never run out of ideas again.

Let’s steal everything we can.

1. Never stop learning

Asimov wasn’t just a science fiction writer. He had a PhD in chemistry from Columbia. He wrote on physics. He wrote on ancient history. Hell, he even wrote a book on the Bible.

Why was he able to write so widely in an age of myopic specialization?

Unlike modern day “professionals,” Asimov’s learning didn’t end with a degree:

I couldn’t possibly write the variety of books I manage to do out of the knowledge I had gained in school alone. I had to keep a program of self-education in process. My library of reference books grew and I found I had to sweat over them in my constant fear that I might misunderstand a point that to someone knowledgeable in the subject would be a ludicrously simple one.

To have good ideas, we need to consume good ideas too. The diploma isn’t the end. If anything, it’s the beginning.

Growing up, Asimov read everything:

All this incredibly miscellaneous reading, the result of lack of guidance, left its indelible mark. My interest was aroused in twenty different directions and all those interests remained. I have written books on mythology, on the Bible, on Shakespeare, on history, on science, and so on.

Read widely. Follow your curiosity. Never stop investing in yourself.

2. Don’t fight getting stuck

It’s refreshing to know that, like myself, Asimov often got stuck:

Frequently, when I am at work on a science-fiction novel, I find myself heartily sick of it and unable to write another word.

Getting stuck is normal. It’s what happens next, our reaction, that separates the professional from the amateur.

Asimov didn’t let getting stuck stop him. Over the years, he developed a strategy:

I don’t stare at blank sheets of paper. I don’t spend days and nights cudgeling a head that is empty of ideas. Instead, I simply leave the novel and go on to any of the dozen other projects that are on tap. I write an editorial, or an essay, or a short story, or work on one of my nonfiction books. By the time I’ve grown tired of these things, my mind has been able to do its proper work and fill up again. I return to my novel and find myself able to write easily once more.

When writing this article, I got so frustrated that I dropped it and worked on other projects for two weeks. Now that I’ve created space, everything feels much, much easier.

The brain works in mysterious ways. By stepping aside, finding other projects, and actively ignoring something, our subconscious creates space for ideas to grow.

3. Beware the resistance

All creatives—be they entrepreneurs, writers, or artists—know the fear of giving shape to ideas. Once we bring something into the world, it’s forever naked to rejection and criticism by millions of angry eyes.

Sometimes, after publishing an article, I am so afraid that I will actively avoid all comments and email correspondence…

This fear is the creative’s greatest enemy. In the The War of Art, Steven Pressfield gives the fear a name.

He calls it “resistance.”

Asimov knows the resistance too:

The ordinary writer is bound to be assailed by insecurities as he writes. Is the sentence he has just created a sensible one? Is it expressed as well as it might be? Would it sound better if it were written differently? The ordinary writer is therefore always revising, always chopping and changing, always trying on different ways of expressing himself, and, for all I know, never being entirely satisfied.

Self-doubt is the mind-killer.

I am a relentless editor. I’ve probably tweaked and re-tweaked this article a dozen times. It still looks like shit. But I must stop now, or I’ll never publish at all.

The fear of rejection makes us into “perfectionists.” But that perfectionism is just a shell. We draw into it when times are hard. It gives us safety… The safety of a lie.

The truth is, all of us have ideas. Little seeds of creativity waft in through the windowsills of the mind. The difference between Asimov and the rest of us is that we reject our ideas before giving them a chance.

After all, never having ideas means never having to fail.

4. Lower your standards

Asimov was fully against the pursuit of perfectionism. Trying to get everything right the first time, he says, is a big mistake.

Instead, get the basics down first:

Think of yourself as an artist making a sketch to get the composition clear in his mind, the blocks of color, the balance, and the rest. With that done, you can worry about the fine points.

Don’t try to paint the Mona Lisa on round one. Lower your standards. Make a test product, a temporary sketch, or a rough draft.

At the same time, Asimov stresses self-assurance:

[A writer] can’t sit around doubting the quality of his writing. Rather, he has to love his own writing. I do.

Believe in your creations. This doesn’t mean you have to make the best in the world on every try. True confidence is about pushing boundaries, failing miserably, and having the strength to stand back up again.

We fail. We struggle. And that is why we succeed.

5. Make MORE stuff

Interestingly, Asimov also recommends making MORE things as a cure for perfectionism:

By the time a particular book is published, the [writer] hasn’t much time to worry about how it will be received or how it will sell. By then he has already sold several others and is working on still others and it is these that concern him. This intensifies the peace and calm of his life.

If you have a new product coming out every few weeks, you simply don’t have time to dwell on failure.

This is why I try to write multiple articles a week instead of focusing on one “perfect” piece. It hurts less when something flops. Diversity is insurance of the mind.

6. The secret sauce

A struggling writer friend of Asimov’s once asked him, “Where do you get your ideas?”

Asimov replied,

By thinking and thinking and thinking till I’m ready to kill myself. […] Did you ever think it was easy to get a good idea?

Many of his nights were spent alone with his mind:

I couldn’t sleep last night so I lay awake thinking of an article to write and I’d think and think and cry at the sad parts. I had a wonderful night.

Nobody ever said having ideas was going to be easy.

If it were, it wouldn’t be worth doing.

This post originally appeared at Medium. Want more? Charles publishes The Open Circle, a free weekly newsletter to over 10,000 readers where he deconstructs high-achievers and shares exclusive lessons from his own learning experiments.