Why high prices, not low wages, are central to understanding Britain’s productivity puzzle

How can we explain the so-called productivity puzzle of rising employment and falling productivity in Britain? That question was again at the forefront of economists’ minds last month with the release of two very interesting papers.

How can we explain the so-called productivity puzzle of rising employment and falling productivity in Britain? That question was again at the forefront of economists’ minds last month with the release of two very interesting papers.

The first was from Professor Jonathan Haskel of Imperial College looking at how official statistics miss the impact of intangible investment on output. His conclusion is that almost a third of the so-called “productivity puzzle” can be explained once intangibles such as computerised information, innovative property (scientific and non-scientific R&D) and finally firm-specific resources (company spending on reputation, human and organisational capital) are accounted for in GDP figures.

That, of course, leaves us with two-thirds of the puzzle still to solve. And here another paper released earlier last month by David Bell and David Blanchflower of the University of Stirling and Dartmouth College respectively may be able to help.

The authors suggest that headline unemployment figures for the UK miss the scale of underemployment in the country. That is, not only are a significant number of people out of work altogether but a number of those in employment currently want to work more hours than they are being offered.

In total the rate of underemployment has risen from 6.2% of the UK workforce in 2008 to 9.9% in 2012, while the unemployment rate grew from 5.8% to 8%.

Bell and Blanchflower claim the main driver of this is a decrease in real wages, with persistent above-target inflation having eroded real incomes consistently over the past five years. Given that price rises have been particularly steep on household costs, such as energy, this seems a compelling conclusion.

Yet to blame falling productivity on lower wages seems something of a circular argument. Instead I think there could be other, more powerful factors at play in labor markets that were largely hidden by buoyant activity during the boom but have only revealed themselves during the Great Recession.

To start with it is important to note that in almost all previous recessions, prices have fallen faster and deeper than wages. Indeed it was this fact that led Ben Bernanke to write in 1994:

“[Slow] nominal-wage adjustment (in the face of massive unemployment) is especially difficult to reconcile with the postulate of economic rationality. We cannot claim to understand the Depression until we can provide a rationale for this paradoxical behavior of wages.”

Any student of economic theory, and particularly of Keynes’ work, will be familiar with the idea that wages can prove “sticky” in a downturn. Part of the explanation for this is that in previous recessions strong labor unions and the existence of legally mandated wage councils helped prevent firms from freezing or cutting their wage bills.

And yet, in the years since the financial crisis this is not what we have seen. Wage growth has remained subdued while prices have continued to increase at far higher rates than most people, including the Bank of England, expected.

So how do we explain this?

An important point to draw out of this is that the relatively impressive job numbers should be looked at cautiously. Effectively stagnant output over the past three years coupled with falling real wages (and therefore demand) does not really make a case for firms to start building up their workforce.

Moreover, as Frances Coppola has discussed, government schemes to get people into work may have had incentives to push people into declaring themselves self-employed without actually being able to earn a living.

The overall trend, however, illustrates that the workforce we have today in the UK is much more flexible than it has been in the past. This comes with a number of benefits, not least preventing employers from having to fire vast swathes of the workforce to reduce costs, but it also has downsides in reducing the ability of employees to negotiate with management over pay.

There is little doubt in my mind that the rate of pay increases in the event of a recovery is likely to be sluggish precisely because of this fact as existing workers compete with each other for additional hours (a fact the authors of the paper point out).

But to me the most important, and so far mostly unexplained, phenomenon is that unlike the US and the euro zone that are both fighting to push inflation upwards towards a target, the UK’s experience has been quite the reverse. This is why our apparent labor market flexibility has not improved the lot of workers as orthodox economic theory suggests it should. In theory, wage flexibility prevents unemployment from rising as high during downturns as it has in the past, and as such should mitigate the risk of hysteresis or lagging effects where workers become de-skilled. Of course, the latter requires the quality of jobs to be maintained as well as the overall quantity of jobs.

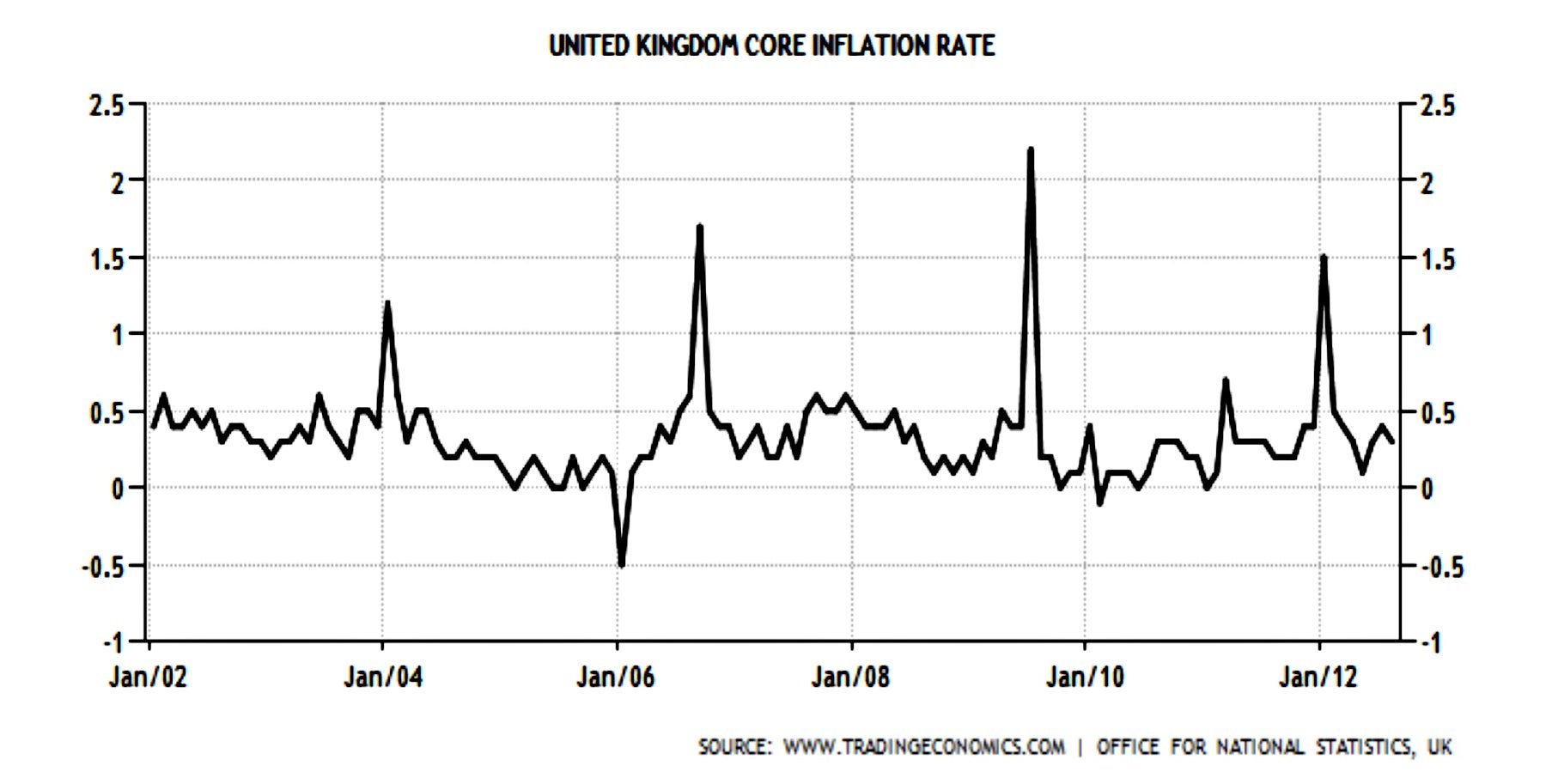

Here the chart below might be of interest (with thanks to John Aziz):

Although core inflation in the UK has been relatively restrained, headline CPI (and household costs) have not. If the real picture of the UK is one of stagnant wages and prices leading to flat-lining GDP growth then the productivity puzzle is far less of a mystery. The question then is whether the apparent increase in labor demand represents anything more than a statistical blip. This to me is where those who want to understand the UK’s puzzling performance might want to start looking.