How a $7.1 billion takeover of a US firm could help tackle China’s strategic pork problem

The biggest takeover yet of a US company by a Chinese one won’t be in telecoms, technology or oil, but something just as strategically important: pork.

The biggest takeover yet of a US company by a Chinese one won’t be in telecoms, technology or oil, but something just as strategically important: pork.

Pork is the meat of China—in fact, the Chinese word for “meat” is literally synonymous with “pork.” With pork making up half the meat consumed, China gobbles up more of it than the rest of the world combined, according to some estimates.

But as China’s hunger for pork has swelled with the population’s growing prosperity, its fragmented hog industry has struggled to keep up. Wild price swings prompted the government enough to create a strategic pork reserve, but the industry is still vulnerable to volatile prices and a spate of food-safety scandals.

That might start to change if China’s biggest pork producer, Shuanghui Group, closes its bid for Smithfield Foods, a US leader in the pig business. At $7.1 billion including debt, Bloomberg estimates that it would be the biggest Chinese purchase of a US company to date.

The deal means Shuanghui would get not only Smithfield’s American-grown hogs, but also its brand and technology, which could help with the Chinese pork industry’s quality-control problems. And there could be similar partnerships across global agribusiness as China’s growing appetite for meat, grains and dairy offsets flattening demand elsewhere.

The world pork balance is shifting

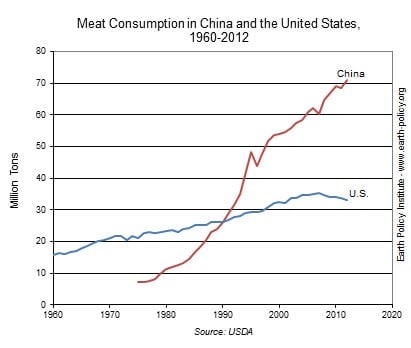

America’s appetite for pork has slid in recent years, so much so that while Smithfield’s packaged-meats business was doing fine, it was facing pressure to split off its unprofitable hog-rearing division. But while Americans’ meat consumption has tailed off, China’s has exploded:

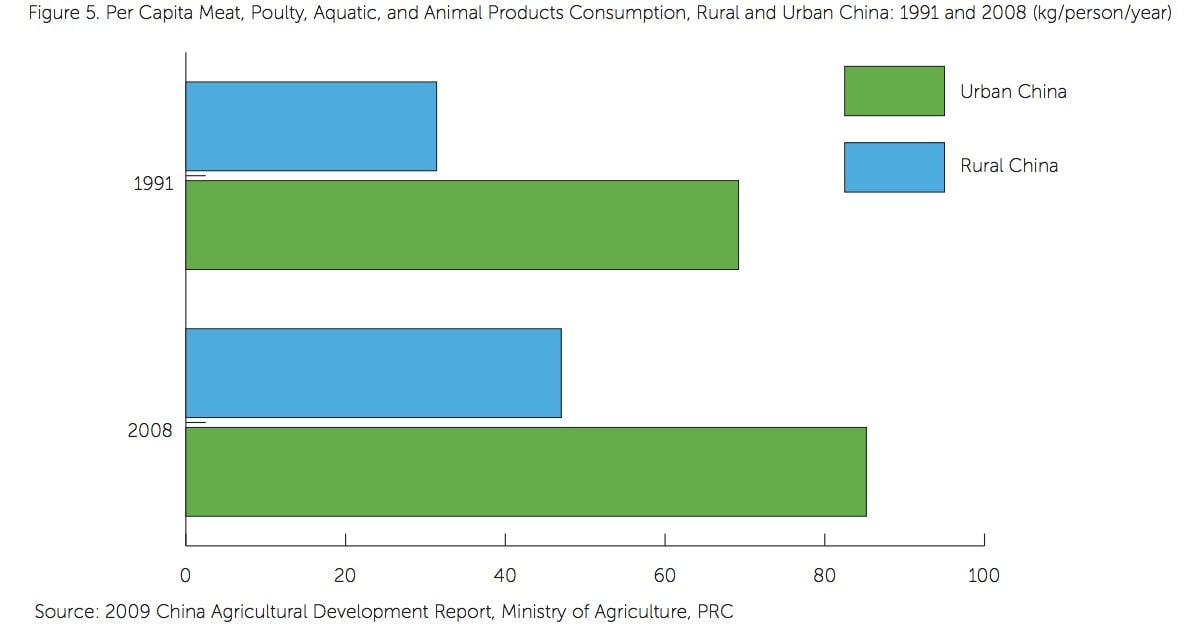

And here’s how China’s own consumption has evolved:

And the world’s hog farmers are scrambling to keep up

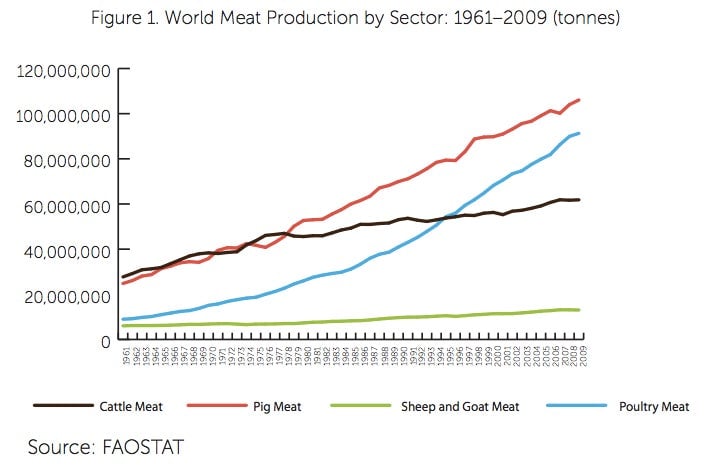

China produced 53.4 million tons (48.4 million tonnes) of pork last year. It’s increased by an average of 1.5% a year in the past decade, but that’s trailed behind demand. China’s appetite for pork has driven global pork production up:

And Chinese companies like Shuanghui—which, though its the country’s biggest pork company, produces less than 3 million tons of the stuff, a sliver of the total—have gone fanning out around the globe in search of agricultural investments. For instance, Chinese investors have backed credit for Latin American farmers producing soybeans, which are used to feed hogs in China. Indeed, the need to find feed for China’s pigs as well as its people is part of the reason for worries about surging corn and soybean prices around the planet.

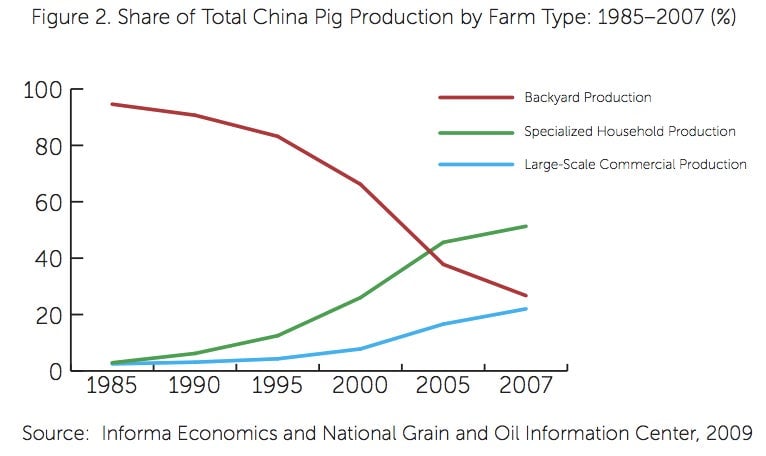

China’s fragmented industry means volatile pork prices

Those high feed prices keep margins thin. That makes things tough for China’s small farmers, who still supply about 30% of China’s total pork output. When prices soar, smaller farmers in particular go all in on piglets to cash in on the bonanza. But that causes a glut within a couple of years that collapses prices—whereupon they get out of the pig business again. Here’s a look at that:

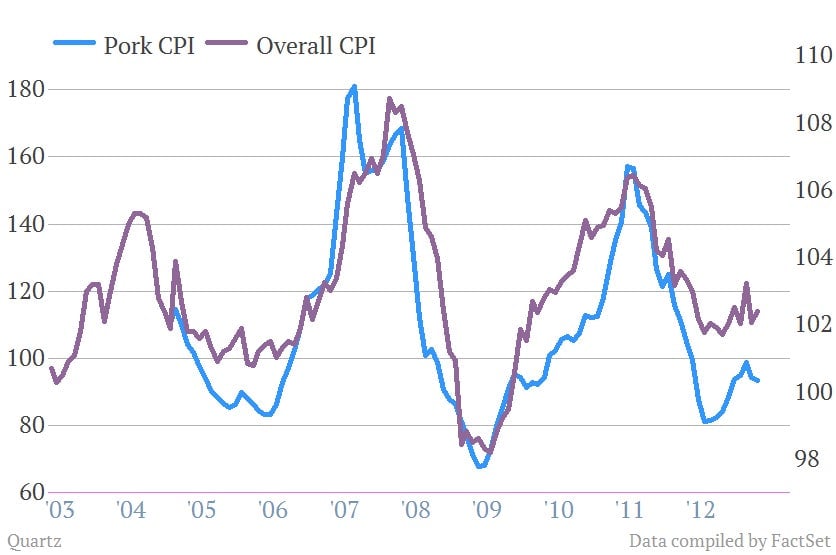

This trend makes China’s hog cycle unusually volatile. Overall fragmentation and inefficiency in the industry make that worse. And that, in turn, sends pork prices on wild spirals every couple of years. On top of that, because China consumes so much of it, pork heavily influences overall inflation, which is a big worry for the Chinese government. Here’s a look at how closely overall consumer prices track pork prices:

The solution to volatility: Freeze lots of pork

See how prices spiked in 2007? That resulted from an outbreak of the blue-eared pig disease in 2006, which saw millions of pigs slaughtered. It was then that the government established a strategic frozen pork reserve to control prices. In fact, it was Smithfield pork that first filled the reserve back in 2007, and that was released in 2008 to help push down prices. The government later decided only to use domestic pork, though; there’s still a deep-seated ideological commitment to Mao Zedong’s notion of agricultural self-sufficiency.

But food safety disasters have bred distrust in Chinese brands

But the growing public awareness of China’s wretched food safety record is making Mao’s vision hard to stick to. Consumers are choosing foreign food brands whose regulators they trust more.

Which is another reason why it makes sense for Shuanghui to buy Smithfield. As with dairy, mutton and other products, tainted pork is also a massive problem, and Shuanghui has had its share of scandals. In 2011, it lost around $3 billion—a quarter of its annual revenue—due to a scandal related to pork doped with an illegal chemical. Then there was that little problem with the maggot-riddled ham. So Acquiring a foreign brand and production base might help restore some trust. And in the longer run, it could learn from Smithfield how to avoid lapses in supply-chain management that are typically at the root of China’s food safety scandals.

And the US has not only pigs, but also pig feed

Another advantage of buying Smithfield is locating hog production close to a supply of corn and soybeans, as well as more ample water supplies—an adult pig typically guzzles 50 liters a day. (The deal would take Smithfield private, making it a Shuanghui subsidiary, and its management would stay in Virginia.)

The deal’s not yet done, though. Shuanghui’s bid will need to clear Committee on Foreign Investment in the US, the government body that reviews deals that concern US security. Smithfield shares were up 25% following the announcement, though, suggesting that investors are pretty confident the deal will go through.

One Chinese state-owned agricultural processing company—COFCO, which runs the pork reserves—had in 2008 bought a 5% stake in Smithfield. Smithfield had hoped that the deal would see it open a joint-venture in China (paywall); when that never materialized, Smithfield bought the stake back in November 2012. Maybe now with Shuanghui, it will get its chance.