Russia’s slowdown isn’t as bad as you think and is likely tied to the euro zone crisis

Russia is a country that tends to bring out overheated reactions from people who study and write about it. Rather than presenting Russia as a middle income country that has a lot in common with many other middle income countries (corruption, popular dissatisfaction, substantial structural limitations to more rapid economic growth) journalists tend to focus on its sins and blow them out of all proportion. Modest economic slowdowns can be presented as catastrophic collapses, and every bit of (unjustified) harassment of the anti-Putin opposition is darkly, and somewhat absurdly, compared to the Great Terror or collectivization.

Russia is a country that tends to bring out overheated reactions from people who study and write about it. Rather than presenting Russia as a middle income country that has a lot in common with many other middle income countries (corruption, popular dissatisfaction, substantial structural limitations to more rapid economic growth) journalists tend to focus on its sins and blow them out of all proportion. Modest economic slowdowns can be presented as catastrophic collapses, and every bit of (unjustified) harassment of the anti-Putin opposition is darkly, and somewhat absurdly, compared to the Great Terror or collectivization.

While I’m skeptical that 2013 will be the year that the Russian economy collapses down around Putin’s ears, by this point it is completely undeniable that its economy has slowed down significantly. In the first quarter of 2013, Russia’s economy was basically stagnant, growing at a rate of around 1%. This was a sharp slowdown from the growth rate of 2012, which itself was marginally lower than 2010 or 2011 and much lower than the pre-2008 boom days.

So what gives? Why is Russia’s economy slowing so dramatically in the first half of 2013? Some people, such as former minister of Finance Alexei Kudrin, argue that the problems are essentially domestic in nature: Russia has reached the limits of its current economic model and must undergo deep supply-side reforms. According to this school of thought, any attempts at stimulus are pointless because they will simply spark inflation (which is the most sensitive political issue in Russia) and only succeed in postponing the day of reckoning. In short, there is no output gap, Russia is growing at or above its capacity, and the country needs to undertake a major change in policy to reassure entrepreneurs and spark investment or it risks immediate stagnation. The relatively tight labor market, Russian unemployment is under 6% and is near a post-Soviet record low, is perhaps the best piece of evidence that this group can bring to bear; it strongly suggests that there isn’t a demand shortfall but a competitiveness problem.

There is clearly something to this, and even the most optimistic analysis of Russia’s economy has to concede that it is hindered by a number of substantial structural problems. In the long term, Russia really will have to make major changes to its policies if it wants to remain competitive and if it wants to continue to grow. But, over the past several years, a lot of people seem to be confusing “desirable structural reforms” with “necessary short term policies” and “potential long-term trends” with “the most recent developments.”

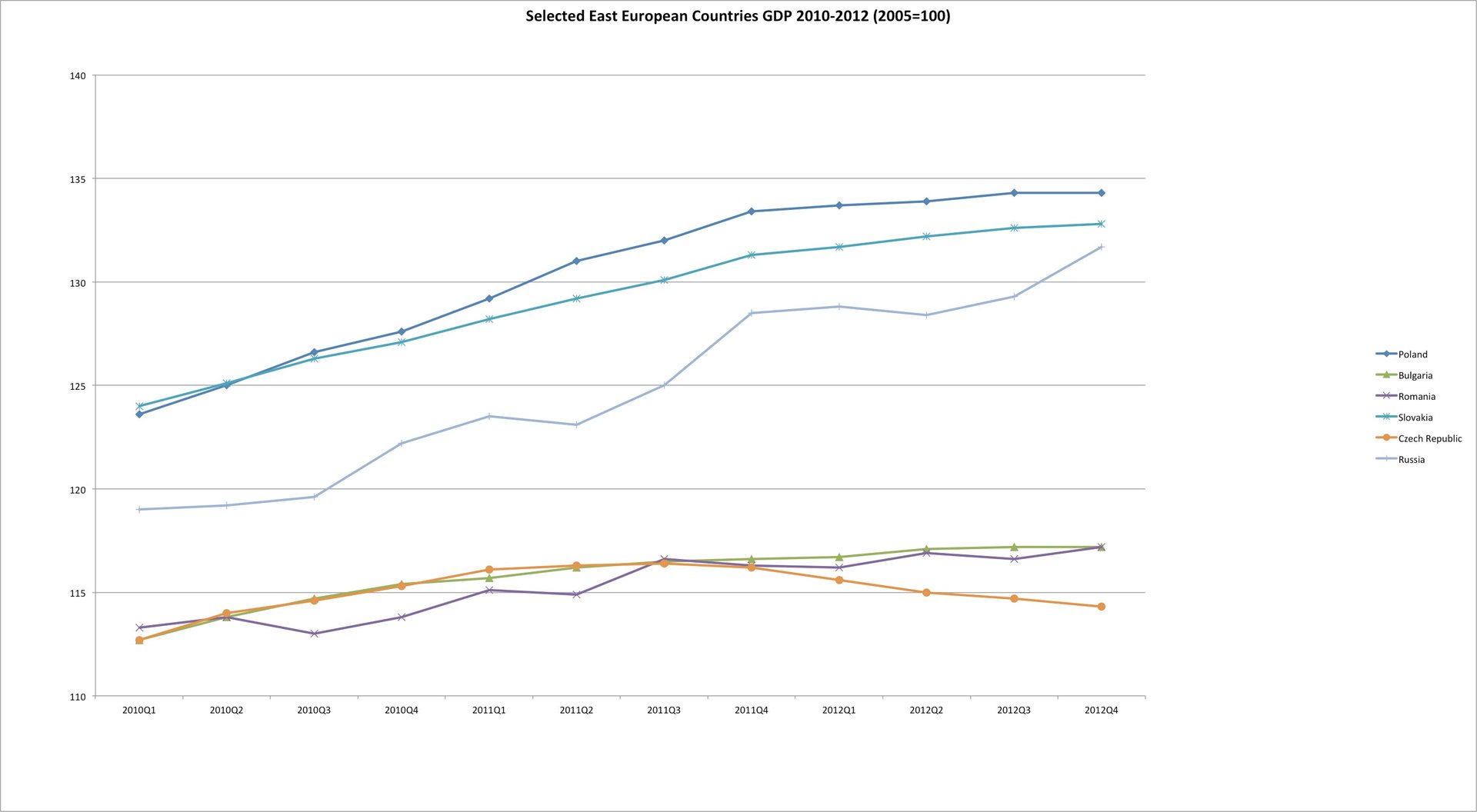

So although Russia has some significant domestic problems, I would argue that the country’s economic deceleration looks a lot less bizarre and inexplicable when you consider its close economic linkages to the European Union and how its immediate neighbors have performed. Here’s a graph of Eurostat and Rosstat data showing how the major post-Communist countries in Eastern Europe have performed since the beginning of 2010 (I omitted Hungary because its performance is so miserable it throws the graph’s scaling off).

What’s noteworthy is that Russia continued to grow after most other countries in the region had started to stagnate. Even usually robust Poland and Slovakia, which have together weathered the economic crisis better than any other countries in Europe, were basically in stasis for the second half of 2012. And the first quarter of 2013 was no better, with Poland growing at an annual rate of 0.4% and Slovakia 0.9%. So Russia, while growing slower than it used to, is still growing faster than other Eastern European countries.

Now perhaps it’s simply a coincidence that, towards the end of 2012 and the beginning of 2013, a broad swathe of countries in eastern Europe, including Russia and Ukraine, all started to weaken economically. You don’t need to go very far beneath the surface of any of these countries to find some pretty serious issues, and you could create a plausible narrative about why any particular country was experiencing problems. However, when the entire eastern European region simultaneously experiences an economic slowdown, I would humbly suggest that there are major international factors at work and that we have to look to the never-ending crisis of the euro zone.