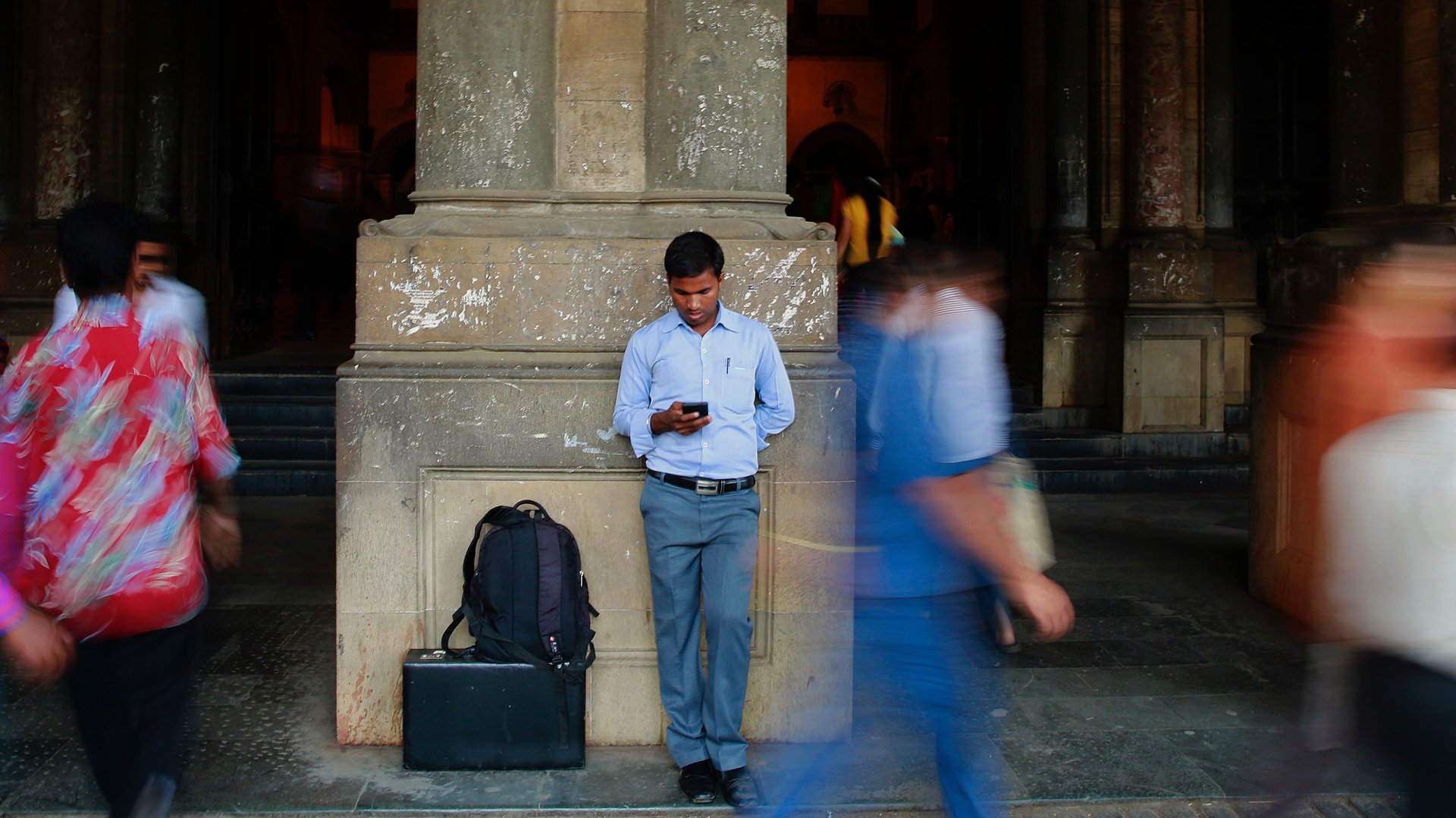

Despite Modi’s “Make In India” initiative, most Indians have Chinese cellphones

Indian smartphone makers are getting beat on their home turf.

Indian smartphone makers are getting beat on their home turf.

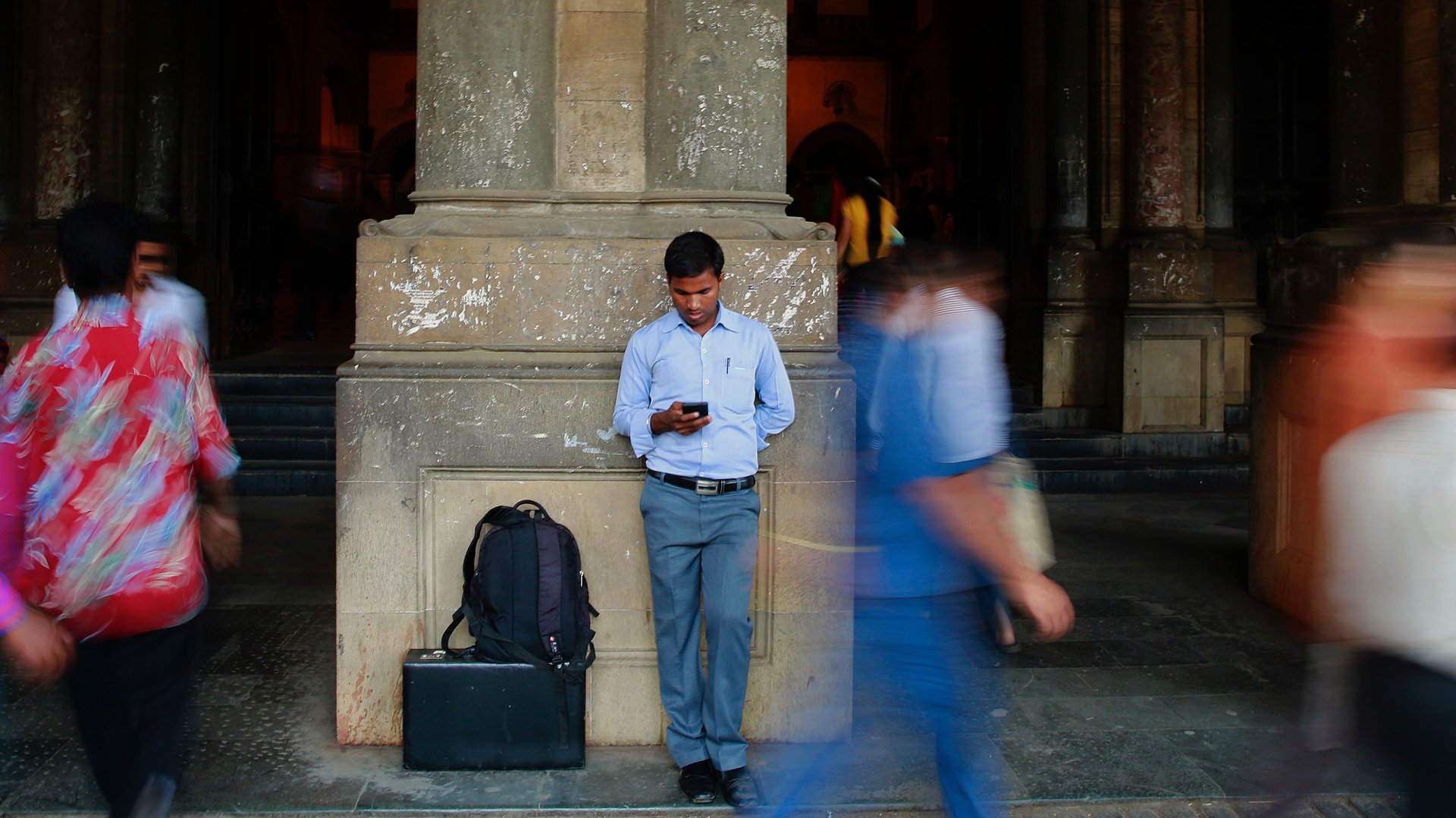

India is currently the world’s fastest-growing smartphone market: Smartphone shipments there increased 18% last year over 2015, according to data from Counterpoint Research, compared with 3% worldwide. As both local and foreign brands vie for a piece of the action in India, it looks like Chinese vendors are coming out on top.

Chinese smartphones accounted for 46% of the Indian smartphone market in the fourth quarter of 2016, up from 14% in the fourth quarter of 2015. Indian manufacturers, meanwhile, saw their smartphone market share in the country plunge to 20% in the fourth quarter from 54% a year earlier.

Indian phone-makers started losing market share in 2015, when Chinese vendors came to the fore with competitive handsets at low prices. In response to growing foreign influence in various industries, prime minister Narendra Modi launched a “Make In India” initiative, encouraging national and multinational companies to source and produce locally. The campaign seemed to energize phone-makers and buyers alike—by mid-2016, locally made devices made up nearly half of the smartphones sold in India—but the success was short-lived.

Modi’s controversial demonetization policy has only exacerbated the problem, as a liquidity crunch plagues the cash-dependent economy. Most smartphone purchases in the country are made with cash in brick-and-mortar stores, especially in non-urban areas. In the wake of demonetization, Indians began to save the limited amount of new currency available to them for necessities instead of luxuries like smartphones. The industry was so badly hit that the Indian Cellular Association (ICA) made a plea to the government to allow them to accept the defunct Rs500 and Rs1,000 notes, which were taken out of circulation in November.

Overall, India’s top 50 cities for smartphone sales saw purchases drop 30.5% between October and November, according to the International Data Corporation (IDC). Among Indian manufacturers, the decline was even more steep, at 37.2%. Chinese vendors saw a 26.5% drop.

The impact is clear when you compare India’s top five smartphone vendors for all of 2016 to those for just the fourth quarter. (Companies with an asterisk next to their name are based in India.) Popular Chinese brands like Vivo, Xiaomi, Lenovo, and Oppo gained market share, mostly at the expense Indian brands.

Of course, demonetization is just one factor. The Indian smartphone market has more than 150 players, all of whom are fighting for relevance. Some Chinese brands started manufacturing locally to drive down costs, while others have focused on offering smartphones with bigger screens and an improved user interface. Others have splurged on marketing campaigns to paint themselves as high-quality but affordable.

For Chinese vendors, producing phones with a retail price point well under India’s $158 average has been coupled with a shift from online sales to brick-and-mortar stores. Only a third of India’s smartphone sales happen online, and physical stores allow phone-makers to tap smaller cities with limited or no internet access. Guangdong-based Oppo, for example, recently set up 35,000 sales points and 180 service centers across India, Bloomberg reported.

And if you think Indian companies like Micromax have an edge by virtue of their regional-language operating systems, think again. Chinese brands are leaving no stone unturned when it comes to localization either: Xiaomi’s new Mi 4i phone supports six Indian languages and counting.