The most tweetable trial in US history happened 300 years ago, and it’s just as relevant today

The trial had everything: snarling prosecutors, riveting young female witness, accusations of the most personal and damaging kind. You couldn’t not have an opinion, watching the drama unfold—or, more likely, reading or hearing a third-hand account.

The trial had everything: snarling prosecutors, riveting young female witness, accusations of the most personal and damaging kind. You couldn’t not have an opinion, watching the drama unfold—or, more likely, reading or hearing a third-hand account.

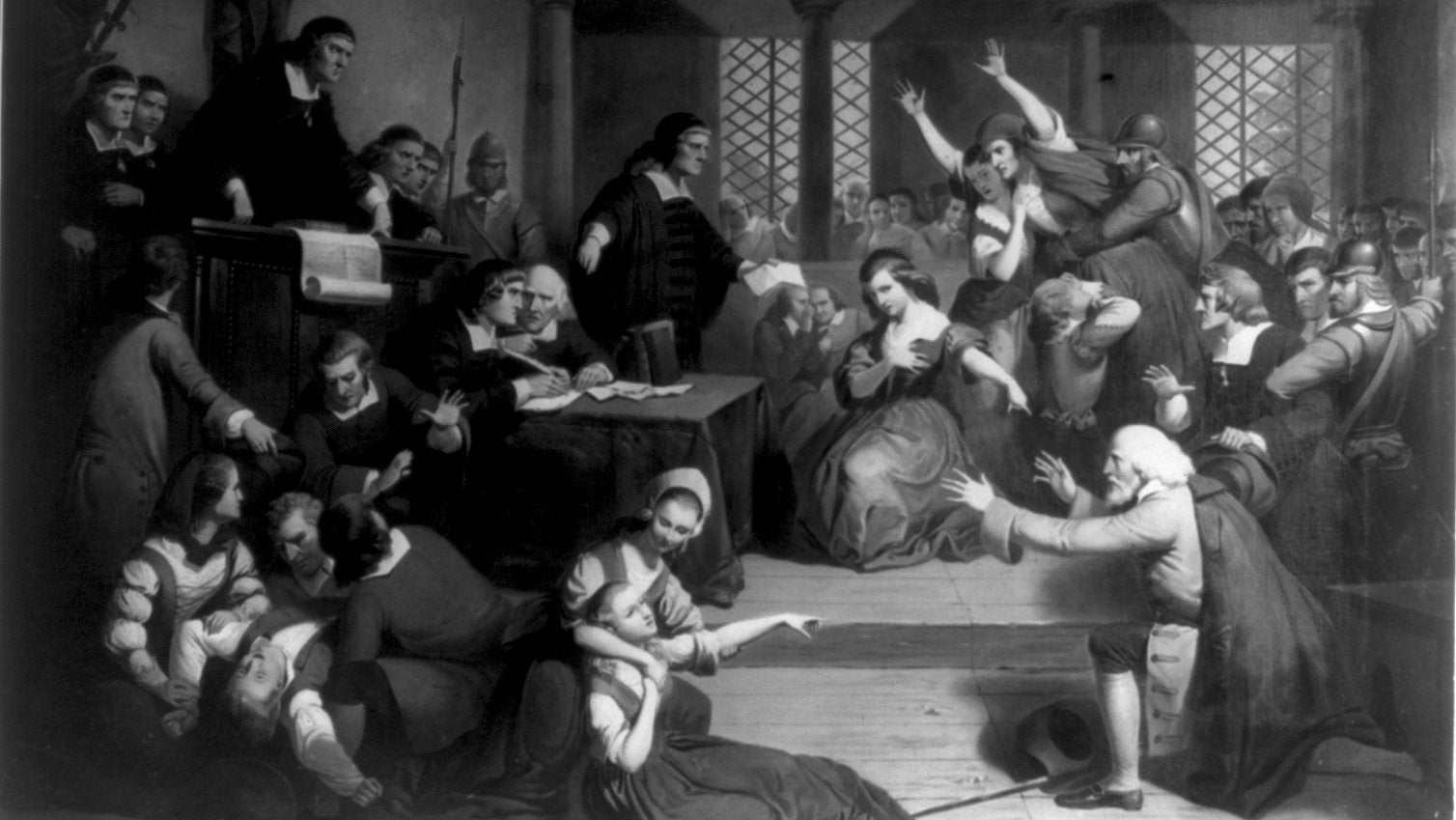

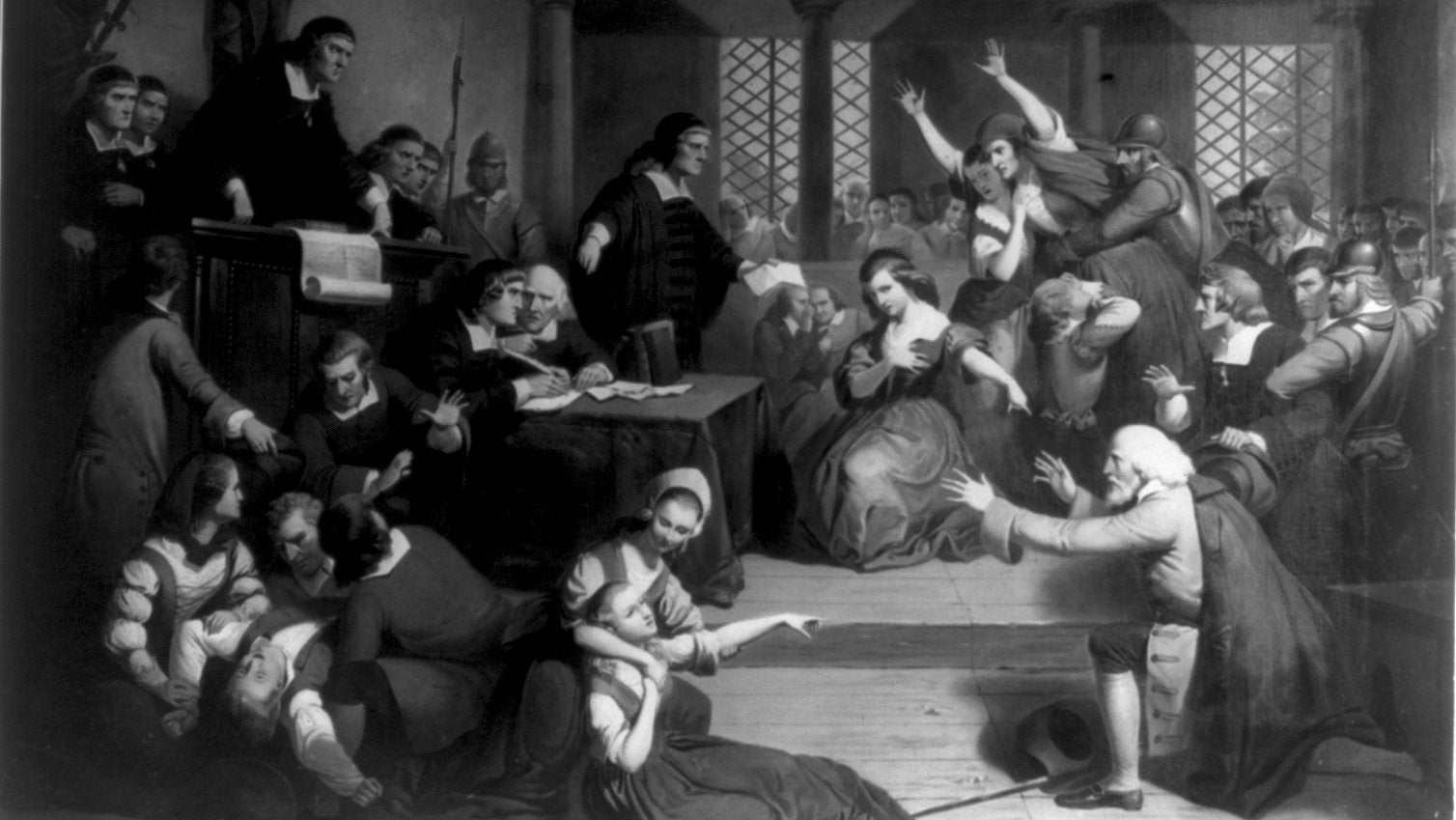

It came at a time when an entire American experiment seemed on the brink of failure. The Puritan settlers of 1692 Massachusetts saw danger to their way of life everywhere: threat of attacks by French soldiers and Native Americans from the outside, and inside the infiltration of no less than the Devil himself.

In the face of this American carnage, what could God-fearing people do but to find those responsible and root them out, as publicly and ruthlessly as possible?

The Salem witch trials, which led to the execution of 20 people in 1692 and 1693, were both a peculiarity of time and place and a timeless example of power unchecked by reason. The trials are relevant, as author and historian Stacy Schiff has written, “whenever we overreach ideologically or prosecute overhastily, when prejudice rears its head or decency slips down the drain, when absolutism threatens to envelop us.”

A new project chronicles the witch trials in a medium that seems made for them: historian Maya Rook is tweeting the events of the witch hunt, 325 years to the day they happened.

“I think people are interested in the dark side of how this nation unfolded,” Rook says. “It’s one of these cautionary tales of getting caught up in some kind of fear and committing actions that later cause a lot of regret.”

This is Rook’s second project of this sort. From 2014 to 2016, she tweeted the daily log of the Donner Party, the 1840s pioneer expedition that ended badly in California’s Sierra Nevada mountains.

These day-by-day chronicles are reminders that history doesn’t always feel significant for the people living it.

“These were real people. They had to live [with] the day-to-day monotony of Puritan life,” Rook says of the witch trials’ characters. “People were bored. And they were scared that their experiment in America was failing. [The trials] gave them something to focus on.”

And what better showcase for a witch hunt than Twitter?

“[If] diabolical compacts sound quaint, the trumped-up hysteria remains eminently modern,” Schiff wrote in 2015. “We are no less given to adrenalized overreactions, all the more easily transmitted with the click of a mouse.”