Chinese investment aid to Sri Lanka has been a major success—for China

Colombo, Sri Lanka

Colombo, Sri Lanka

Every day as dusk falls on Colombo, residents flock to Galle Face Green, a vast esplanade facing the beach and Indian Ocean beyond. Snack sellers serve refreshments from rickety tables while families and couples stroll by, hair and dupattas (scarves) fluttering in the wind. One of the most popular parks in town, it’s a great place to people-watch, or just stare at the turbulent waters gleaming in the sunset.

Head north on the adjoining Galle Main Road, and the ocean is soon blocked from view by the largest building site the area has ever seen: the $1.4 billion Colombo Port City project. The project will reclaim some 2 sq km (.77 sq miles) of land, on which will sit luxury flats, office buildings, and hotels, not to mention a theme park, marina, and golf course. For now, it is just an immense construction site.

Looming over the project, and indeed the entire Sri Lankan economy, is China. Chinese-funded investment and infrastructure have been pouring into Sri Lanka in the past decade. The biggest legacy of Beijing’s “help,” however, looks to be a debt-glut that will take at least a couple of generations for the island nation to repay—and Chinese access to strategic Indian Ocean real estate for the next century or so.

“China lends money to countries so that they can build infrastructure that is built by Chinese firms,” said Christopher Balding, associate professor at the HSBC School of Business at Peking University in Shenzhen. “Infrastructure is built. The money is sent back to Chinese firms. The country now has new infrastructure, and a lot more debt.”

The debt, in turn, can result in Beijing getting something rather useful in nations with resources it covets: negotiating leverage to gain access to those resources, including land.

It’s a pattern seen in other countries that have long indulged in Chinese investments, including Venezuela and Cameroon. And it’s one likely to repeat as China continues work on its One Belt, One Road (OBOR) intitiative, designed to connect the Eurasian landmass by land and sea. That includes countries like Laos and Pakistan, both of which have indulged in Chinese funding.

And while China has long practiced “checkbook diplomacy,” alarm bells are ringing (paywall) over the trail of debt being left behind.

Political repercussions

Beyond the mesh wire guarding the Colombo Port City project—with warning signs in Sinhalese, Tamil, and Chinese—heavy machinery dredges, breaks rocks, and lifts boulders. Diggers fill trucks with sand. Chinese engineers look studiously at their printouts, while workers sweat under their helmets.

The project is under the supervision of China Communications Construction Company (CCCC), with its subsidiary China Harbour Engineering Company (CHEC) handling much of the workload. Until this month CCCC and all its subsidiaries were blacklisted by the World Bank for corrupt practices, stemming from a project in the Philippines. That made it ineligible for the past eight years to build bridges or roads backed by World Bank funding anywhere in the world.

For Sri Lanka, that meant all the projects undertaken by CCCC involved no other international credit institution like the World Bank—and ended up being entirely financed by China.

Balding likens China’s approach to Sri Lanka to the one that Chinese state firms have toward national infrastructure projects back home, which have generated significant GDP growth while inflating the ballooning domestic debt.

“In China, this financing model of building infrastructure and [worrying] about the associated debt later is common,” he said. “Whether it’s airports, most of which lose money, or train lines, most of which require enormous subsidies to keep from exploding their debt burden.”

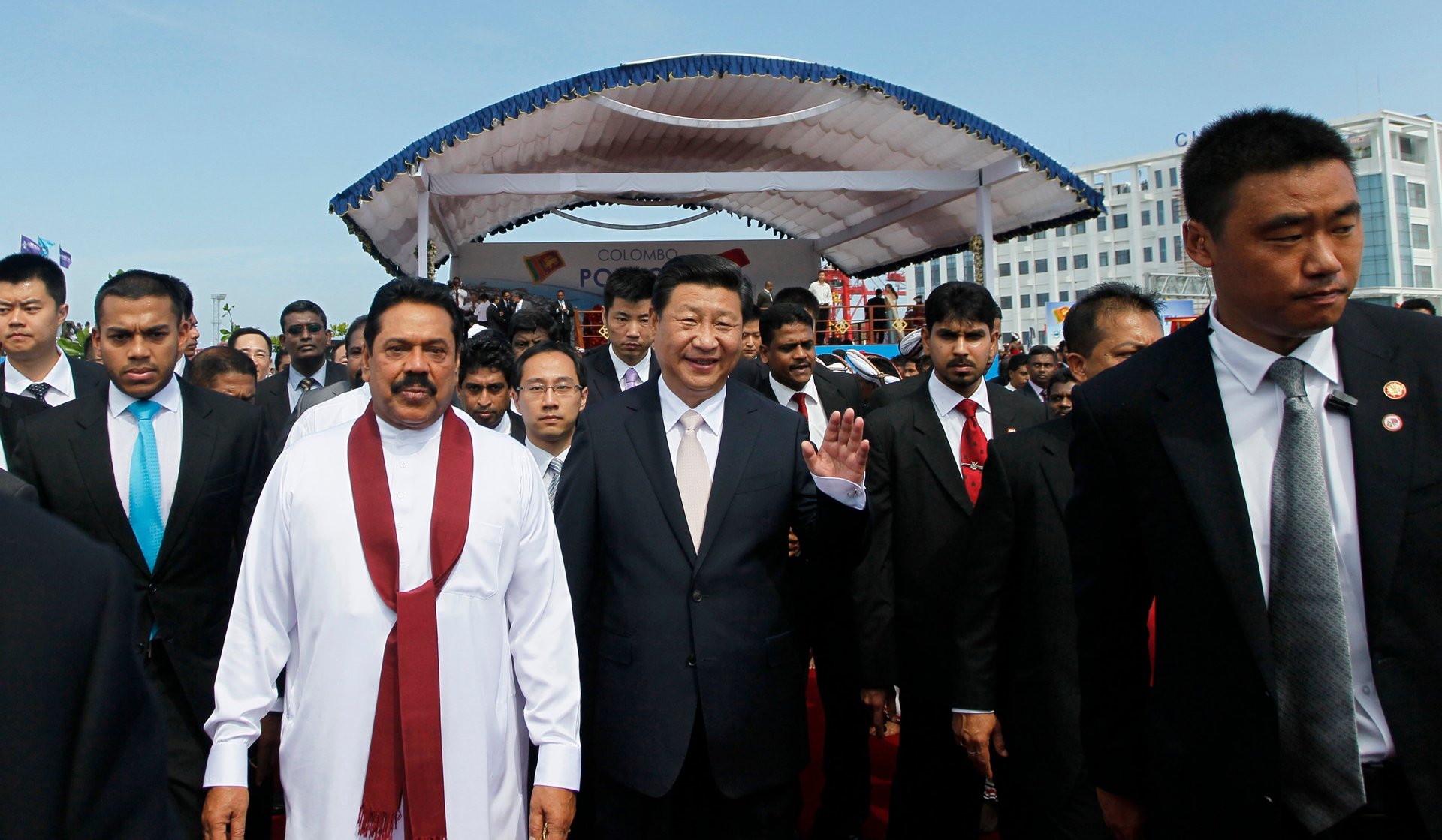

The Colombo Port City project, inaugurated by Chinese president Xi Jinping in 2014, was one of the main deals signed by previous Sri Lankan president Mahinda Rajapaksa. The circumstances under which Rajapaksa agreed to the project were deemed so dubious that they contributed to his electoral defeat in the 2015 presidential elections, ending his 10-year stint at the country’s helm. In a surprise upset, the popular vote went to the United National Party (UNP), as the electorate grew tired of a government renowned for human rights abuses and plagued by allegations of corruption, often involving Chinese investment deals.

After taking power in early 2015, current Sri Lanka president Maithripala Sirisena and his cabinet were keen to reassess all the big infrastructure projects involving Chinese companies. The UNP formed a coalition government with the Sri Lanka Freedom Party, and the new administration put on hold for reexamination the majority of the accords that had been signed with China.

The administration halted work at Colombo Port City by citing the need for a proper environmental impact assessment. (CCCC complained about hefty losses as its machinery and laborers remained idle.) One issue Sirisena and his team sought to address: a generous freehold given to China on 50 hectares of land in the Colombo port area. The new administration negotiated that down to a more limited arrangement, but one Beijing probably still didn’t mind: a 99-year lease on 110 hectares of reclaimed land.

As the new administration quickly discovered, the debt Sri Lanka contracted with China was already too big to work around. It now amounts to $8 billion; meanwhile, 95.4% of all government revenue is currently going towards debt repayment.

The world’s emptiest airport

Not all of the China-fueled infrastructure in Sri Lanka (and other countries) is a white elephant: The Colombo International Container Terminal, also financed through Chinese loans and built by Chinese companies, is already profitable.

But many of the projects are indeed of questionable use. Some of the most striking examples are found around the southern city of Hambantota, the hometown and power base of former president Rajapaksa. One of them, the Mattala International Airport, has been dubbed “the world’s emptiest international airport.” A cricket field and real estate developments nearby look little used, as well.

And then there’s the local port project in Hambantota. The first phase of Magampura Mahinda Rajapaksa Port—yes, it’s named after the former president—opened for business in 2010. Costing over $1 billion, the port has proven to be a money-loser.

But here, too, the Sirisena administration, faced with maturing debt, had to agree to an “equity swap” with China. Last October China Merchants Port Holdings secured a 99-year lease of the port with an 80% stake, along with 15,000 acres of land around it for a projected industrial zone for Chinese investors. In exchange China forgave most of the debt Sri Lanka acquired to develop the port in the first place. Beijing ended up with a strategically located outpost on the Indian Ocean, a nice piece of the OBOR puzzle.

For Sirisena, the choice was to either make a huge default or essentially turn the port over to China. Of course not everybody was happy with the deal—as evidenced by this month’s local protests against Chinese “colonization.”

“The government is quite desperate,” said Anantha Perera, a researcher at Columbia University’s Dart Center. “They came into power in 2015, and one of the hopes was that—based on their policies—they would be able to attract investment from other sources. That has not materialized, leaving Sri Lanka with a huge debt issue that was created by the previous administration, but has come to maturity now.”

No other country has been quite so interested in investing in Sri Lanka as China. That’s as true today as it was during Sri Lanka’s brutal 26-year civil war, which pitted the minority Tamil population in the northeast against the majority Sinhalese.

From 2005 to 2009, as the war was at its worst, China seemed to be the most reliable friend Sri Lankan leaders had, even shielding them from condemnation at the UN Security Council. “China sold a lot of weapons and lent a lot of money to Sri Lanka and remained a useful ally even in the Human Rights Council, all through the end of the war,” said Alan Keenan, a Sri Lanka project director at International Crisis Group.

But what seemed to be pure political logic at the time led to economic arrangements, too—mostly beneficial to China. After the Rajapaksa regime put an end to the ethnic insurgency in the north—killing an estimated 40,000 civilians in the process—it embarked on a foreign-funded construction spree. While risk-averse international investors kept Sri Lanka at arm’s length, China was ready and willing to help.

A considerable gap

Today, as Sri Lanka scrambles to service its debt and attract other foreign investors, China’s assistance looks less positive than it used to.

Last year Sri Lankan finance minister Ravi Karunanayake complained that the interest rates on the loans from China were too high, resulting in a public spat with China’s ambassador, who defended the rates.

“There seems to be a considerable gap between the perception of how beneficial Chinese investments abroad are, and the reality,” said Juan Pablo Cardenal, author of various books on Chinese investments in the world. In many cases these investments come with environmental, labor, or social issues that “should make us revisit how beneficial to the country they may truly be.”

“It will be interesting to see how other countries deal with China now that they know how China plays these things,” said Balding, referring to both the high interest rates and Beijing’s increasing assertiveness in Sri Lanka.

The Philippines, for instance, is eagerly accepting Chinese infrastructure investments, notably for Davao City, the home town and power base of mercurial president Rodrigo Duterte, and Mindanao, the island it’s on.

Meanwhile, thousands of Chinese workers have been brought in to Sri Lanka to work on projects like Colombo Port City. The exact number is contested, but in a country with high unemployment, their presence is a political hot potato.

Mr. Chen, a manual laborer from Chongqing in southwest China, has spent more than two years at the project. “We work long days,” he said, asking to be identified by his last name only. “About 10 hours, sometimes more. In the evening we go back to the dorms, and start again the day after.”

Chen, who’s never had a Lankan meal while on the project, doesn’t know how long CHEC will keep him in the country. But he does know one thing: “This port will be controlled by China for decades.”