There’s a key way to get kids to read more books—and enjoy it

It has become conventional thought that gamification—the application of game-style challenges and rewards to traditional tasks—is changing the way kids learn. If there’s something being taught, it’s almost certain there’s now a gamified way to learn it.

It has become conventional thought that gamification—the application of game-style challenges and rewards to traditional tasks—is changing the way kids learn. If there’s something being taught, it’s almost certain there’s now a gamified way to learn it.

Making teaching methods more entertaining is clearly beneficial for kids; earning badges and unlocking avatars makes online games exciting and engaging, and the same methods can be applied to learning tasks. But as great as it has been in many cases, gamified learning isn’t a long-term solution for children and literacy. Moreover, it’s dragging us away from what the fundamental reward should actually be: reading itself.

As the founder of what was once one of the largest social-gaming companies, I understand what makes gaming work. But I also understand its limitations. While the fun activities and rewards in games may be helpful to engage and motivate some kids, when it comes to reading, they are not a long-term answer. All those badges and avatars won’t get kids to persevere with a book if it isn’t geared to the child’s correct reading level or the subject matter isn’t of interest. Moreover, academic studies shows that youngsters that earn rewards for activities are likely to stop doing those activities when the rewards stop—but kids who do the same things without rewards are likely to continue, just for fun.

This especially significant when it comes to reading.

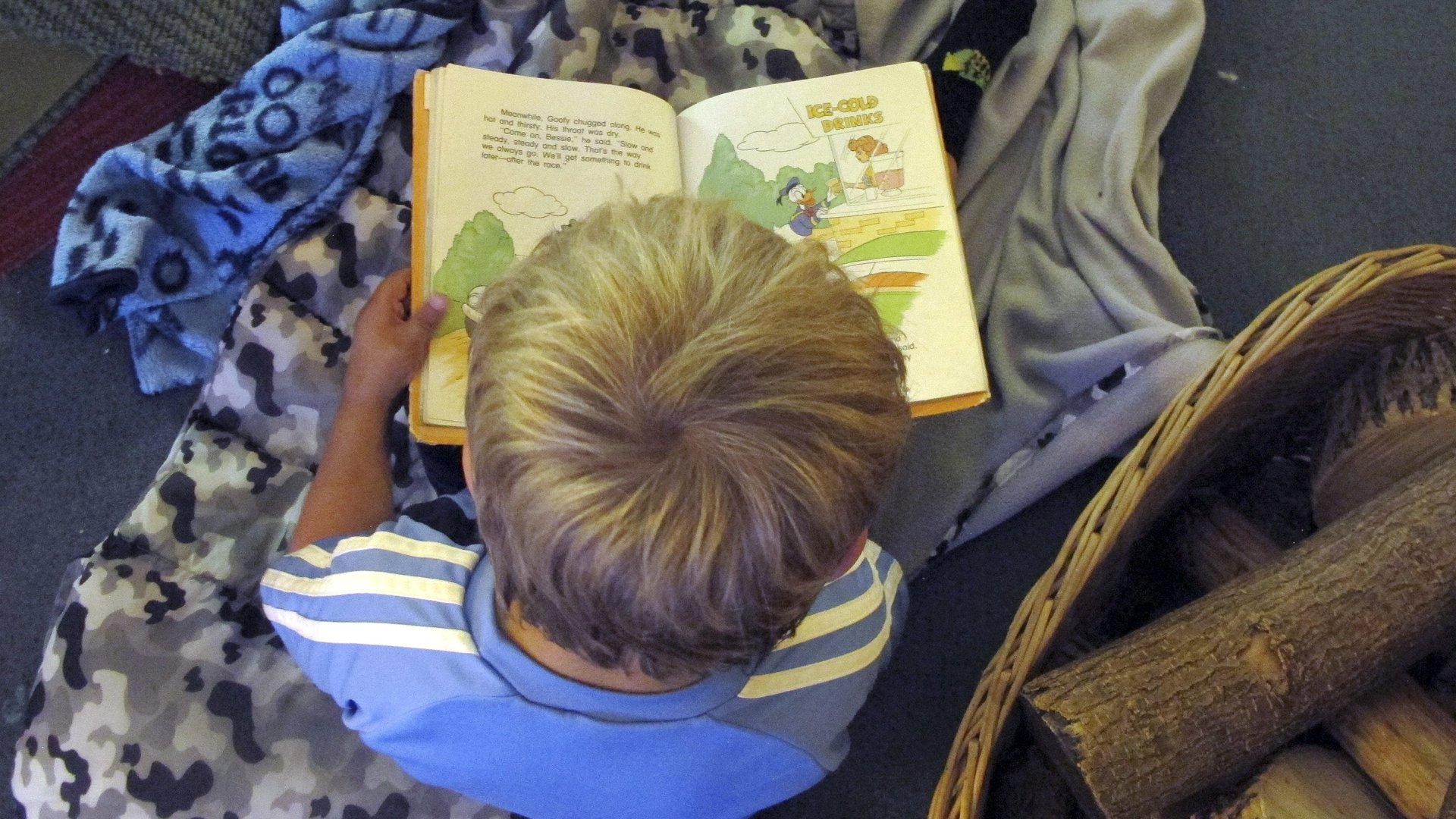

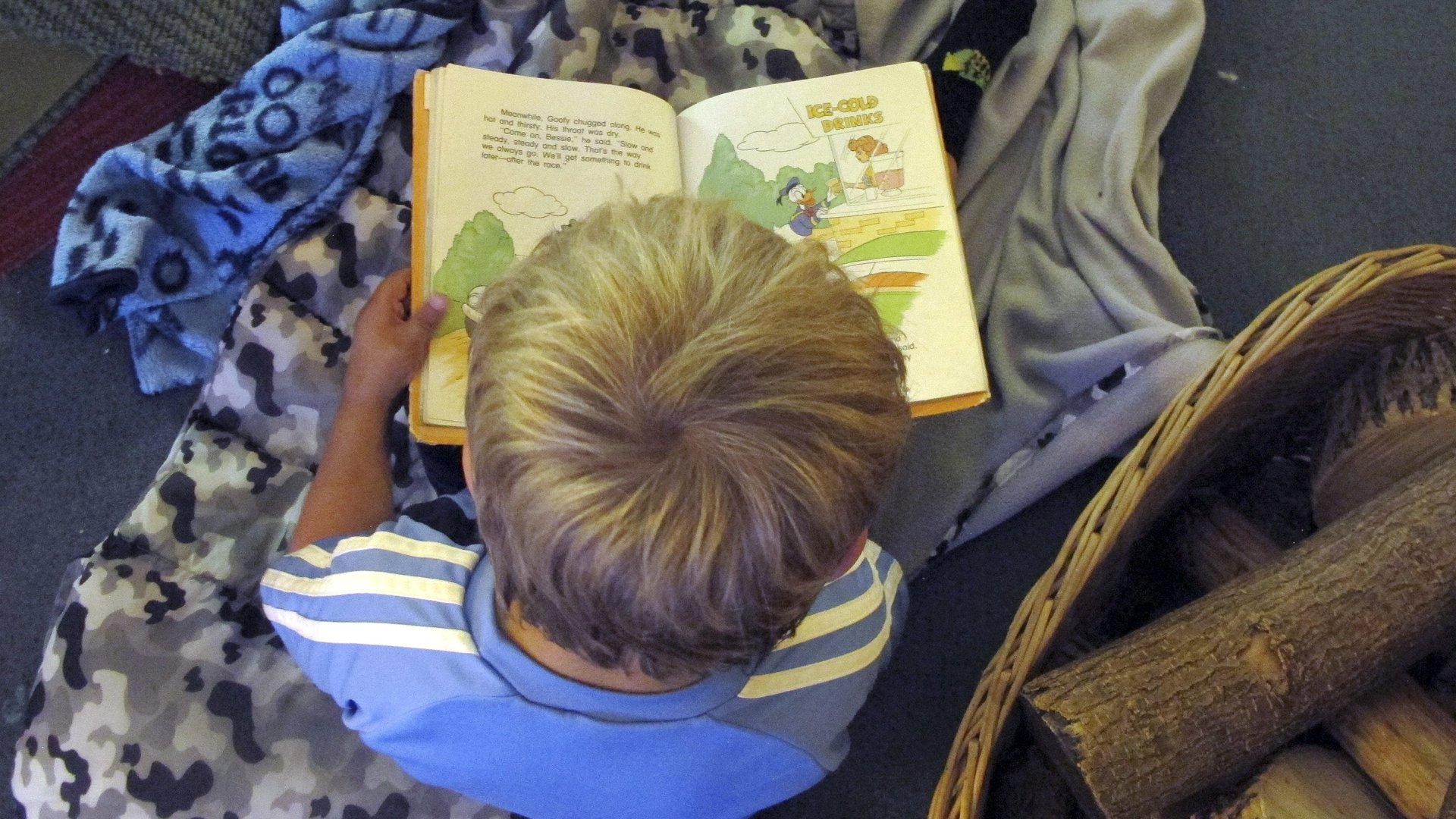

Kids look for content that excites them, for language they understand, and for the experience a book will bring them. Have you ever watched children choosing books at a library or bookstore? They don’t pick books based on title, author, or jacket description the way we adults do. Instead, they spend time exploring each book, opening and paging through it, skimming a page here, looking at a picture there. Then they close it and open the next one.

No amount of game play or virtual-reward system is going to change that shopping dynamic of trying, testing, and browsing for a good fit. Providing appropriate content and frictionless access to a huge selection of books will enable and expand children’s browsing—and this is far more powerful than any external reward system.

Any child will read—or want to be read to—if they can choose the right book and access it instantly. But what is the right book? It isn’t one with the best game-play: It’s the one that explores a subject the child is excited about at that moment. It could be butterflies or baseball, buildings or ballet. For my son, it was fire trucks. Tomorrow, it could be something else entirely.

That’s why selection and variety are essential when it comes to exposing kids to books. We stumble when we force children to read specific books or when they don’t have access to books on subjects that interest them. Whether they’re digital or tangible, libraries still matter for kids. Young people need the opportunity to open as many books as they please until they find the ones they want to read. That way, reading is the reward instead of the price they have to pay in order to earn something else.

Imagine if Netflix only offered science-fiction movies instead of a wide variety of different genres, or if iTunes only sold music by 1980s rock bands. This is the experience that many children often feel they have when it comes to the variety of books they have easily available to them. Entertainment services like these offer many choices, because wide choices attract even wider audiences and keep people coming back.

Reading and literacy are no different.

Epic!, the digital reading resource I cofounded, focuses on reader-driven, instantly accessible reading choices. The free resource for teachers and school librarians offers more than 20,000 titles for kids under 12, and young readers are using it to access more than 400,000 books a day. Many teachers who use the service report that even their most reluctant readers are inspired to read by the power of personal interest.

Getting early reading right in the digital era is more than academic. According to the literacy advocacy group Begin to Read, two thirds of students in America who cannot read proficiently by the end of fourth grade will end up in jail or on welfare. Parents, teachers, and technophiles must therefore encourage children to develop a love of literature by unlocking a universe of diverse book options where they can find things they want to read. Technology can make a real difference in how any why kids read—but it should do so by expanding the reach and convenience of options, not by adding bells and whistles.