Why Donald Trump’s Treasury pick misled Congress about how his bank seized homes

The promise of Donald Trump’s administration, at least to its supporters, is an end to faceless bureaucracies denying them the help they deserve. The man he wants as US Treasury secretary could tell a story about how he fought such a bureaucracy. But that story would entail admitting that banks played a part in the financial crisis—something that the Trump administration and its backers in the financial sector simply can’t do.

The promise of Donald Trump’s administration, at least to its supporters, is an end to faceless bureaucracies denying them the help they deserve. The man he wants as US Treasury secretary could tell a story about how he fought such a bureaucracy. But that story would entail admitting that banks played a part in the financial crisis—something that the Trump administration and its backers in the financial sector simply can’t do.

The nominee, Steve Mnuchin, ran a bank called OneWest, formerly known as IndyMac, from 2009 to 2015. He and his team purchased it out of insolvency during the financial crisis, righted the ship, and sold it for a nice profit. A big part of the recovery was getting delinquent loans off the books—that is to say, foreclosing on homeowners who couldn’t afford to make payments anymore.

A common practice among many banks at the time was something called “robo-signing.” With so many foreclosures to be done and so little time to do them, bank employees began to sign sworn affidavits without performing basic legal reviews of who truly owned a house or whether they had been given a chance to modify their loan. Many Americans lost their homes wrongly and without due process, and banks had to pay a $9.3 billion settlement because of it—still, many critics say they got off easy.

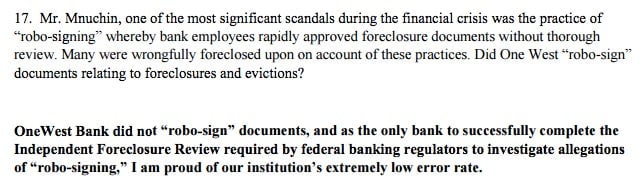

Did Mnuchin’s bank robo-sign? Here’s what he said in his official questionnaire when asked by senators:

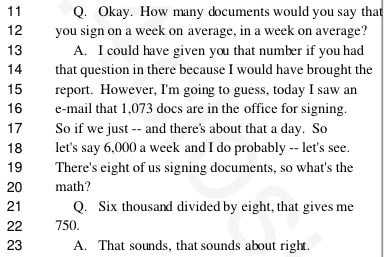

But the record doesn’t really back this statement. Here’s an excerpt from a 2009 deposition of a OneWest VP in Texas who worked in foreclosures. It was taken four months after Mnuchin bought the bank:

If that VP was working 60 hours a week, she was signing off on more than 12 foreclosures every single hour. But that would even be an overestimate of the time spent: The VP goes on to explain that she didn’t spot check the documents she signed or fill in the numbers, leaving that to an outside contractor. She changed her signature to one letter—”E”—and got the process down to 30 seconds per foreclosure.

Mnuchin’s defenders say that this deposition has been cited in court by borrowers battling OneWest foreclosures, and judges have ruled that the methods described were not improper.

“The media is picking on a hardworking bank employee whose reputation has been maligned but whose work has been upheld by numerous courts all around the country in the face of scurrilous and false allegations,” Barney Keller, Mnuchin’s spokesperson, said in a statement.

Yet in Ohio, the Columbus Dispatch found that into 2010 and beyond, OneWest was foreclosing on homes at a rapid pace using out-of-state signers in Texas, and noted that a local judge had dismissed at least three cases because of robo-signing-related inaccuracies. In New Jersey, OneWest was temporarily banned from any foreclosures at all due to robo-signing concerns, and New York judges overturned some of its defaults on similar grounds. In 2011, Reuters found foreclosure documents filed by OneWest three months before the bank legally owned the home in question.

It’s clear many of One West’s foreclosures involved predatory loans issued by the bank before Mnuchin purchased it. Mnuchin could have acknowledged that these loans led to IndyMac’s failure, and that his team, under the banner of the OneWest brand, cleaned them up. But here’s where things really get complicated.

During his testimony, he noted the bank’s emphasis on loan modifications, without noting that the government paid banks to do these. That makes his outright denial of robo-signing even more interesting, especially in context of the Independent Foreclosure review Mnuchin mentions in his remarks.

That review stems from a 2011 government order, more than two years after Mnuchin bought the bank. The bank’s regulators specifically said the company was having its employees sign legal documents making assertions they didn’t have personal knowledge of, and the bank promised “to remedy the deficiencies and unsafe or unsound practices” while neither admitting nor denying them.

This entailed hiring consultants to review the bank’s foreclosure process for problems. When Mnuchin says his bank was the only one to “successfully complete” the Independent Foreclosure Review, it simply means that the relatively small bank with fewer than 200,000 loans to review was able to pay back the customers it harmed in a timely fashion after the government told it to perform the audit. Larger banks with millions of troubled loans were forced to pay into the $9.3 billion settlement fund.

“The review found that not only did OneWest not engage in anything that could be considered ‘robosigning,’ but that it had the lowest error rate of any major bank and was the most successful at offering loan modifications where appropriate,” Keller said. “Steven is proud of his record at OneWest, and looks forward to getting to work on behalf of the American people if confirmed by the Senate.”

In 2014, the final public report from One West’s regulator noted that after reviewing “a substantial” number of eligible loans, 5.6% or 10,871 borrowers were found to be due $8.5 million in remediation. This included 23 borrowers who were not actually in default when their loans were called in.

By the standards of American finance, this is practically a tale of heroism: OneWest only had to be told once by the government to stop abusing its customers before it attempted to make them whole.

But leaning into such a narrative would require admitting that those initial toxic loans, with their high fees, interest-only structures, ballooning payments, or no-money down options, were part of the problem. That’s impossible for Mnuchin and the Trump administration, which has voiced support for rolling back the post-crisis rules designed to prevent these kinds of predatory loans from being made at all.

While Democrats are largely united in opposition to Mnuchin, it appears he retains the backing of the Republican senators he’ll need to take his job. A vote is expected this week.

This story was updated with additional comment.