Photos and campaign billboards capture the legacy of one of Africa’s most delusional autocrats

When The Gambia’s former president Yahya Jammeh first came to power in 1994 as a 29-year old army lieutenant after a bloodless coup, few Gambians would have guessed that by the time he left office 22 years later it would be as a corrupt and delusional leader hanging onto power.

When The Gambia’s former president Yahya Jammeh first came to power in 1994 as a 29-year old army lieutenant after a bloodless coup, few Gambians would have guessed that by the time he left office 22 years later it would be as a corrupt and delusional leader hanging onto power.

Over the years it became increasingly clear that Jammeh was losing touch with reality even as his country’s economy floundered. Young Gambians risked their lives crossing the Mediterranean to get to Europe in above average numbers for such a small population of less than two million people. Meanwhile, Jammeh went after his opponents, claimed to have found an herbal cure for AIDS, and promised to rule his country for a billion years.

His eccentricities became all the more obvious in his wardrobe choices. While he is best known in recent years for his all-white ensembles, Jammeh started out in military uniform before experimenting with a range of headgear and staffs in his early days as a civilian president.

But that didn’t make him any less dangerous to his countrymen and women who tried to stand up to his autocratic rule over five elections between 1996 to 2016. At least three of the four elections that he won were under questionable circumstances.

After consolidating power, it became difficult to step down even after publicly accepting defeat to president Adama Barrow, live on national television. He changed his mind days later, throwing his country into a political crisis that didn’t end until troops from neighbor Senegal, under the auspices of ECOWAS, entered the country.

With a legacy that ended so dramatically it may be too soon to close the book on what Jammeh’s 22 years meant for Gambians, but many celebrated his exit, especially activists who had campaigned for better democratic standards for years.

“The worst thing that ever happened to Gambia”

Most said that they would not remember the leader fondly. ”He was a repressive leader who thought he was the messiah and did all he could to stay in power by all means especially in the last 12 years of his rule,” says Aisha Dabo, a journalist in Banjul and a member of Africtivistes, a group of cyber activists promoting democracy in Africa.

“I will remember him as a tyrant and a selfish dishonest dictator, says Cherno Omar Barry, a former permanent secretary in the country’s education ministry. “His name makes me think of fear and then loathing.”

Raffie Diab, an entrepreneur in Banjul, describes Jammeh as ”the worst thing that ever happened to Gambia.” He added that the former president’s reputation for disappearing critics and opposition activists meant that many Gambians lived in fear.

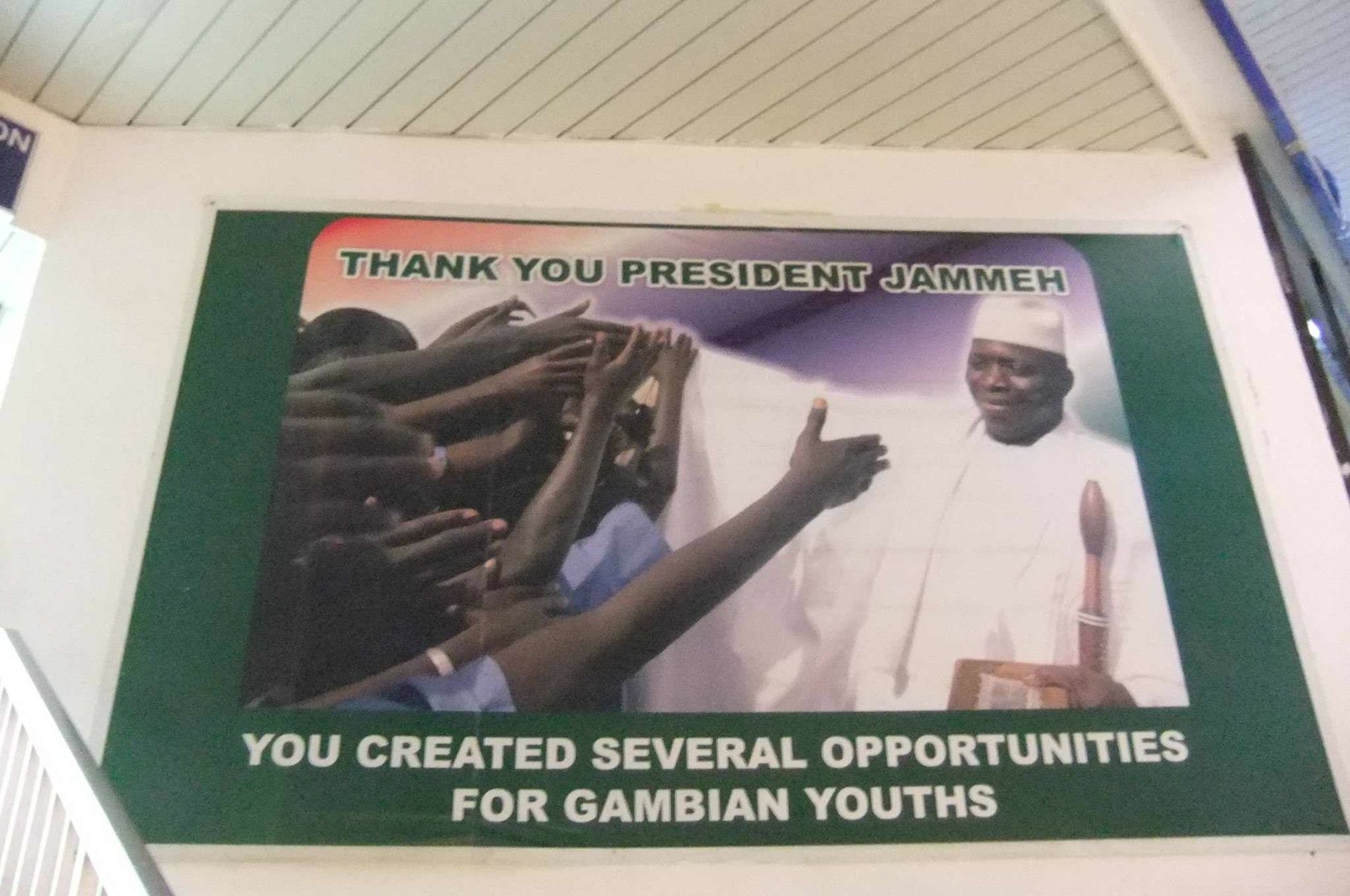

There’s one noticeable difference in Gambia since the departure of Jammeh. The posters and billboards featuring Jammeh’s face throughout the country have been taken down. Lamin Ceesay, 26, used to see these every day. “At some point I became used to seeing them,” he said. ”There used to be lots of his billboards… but for now all pictures and billboards of him are no more, even within public offices.”

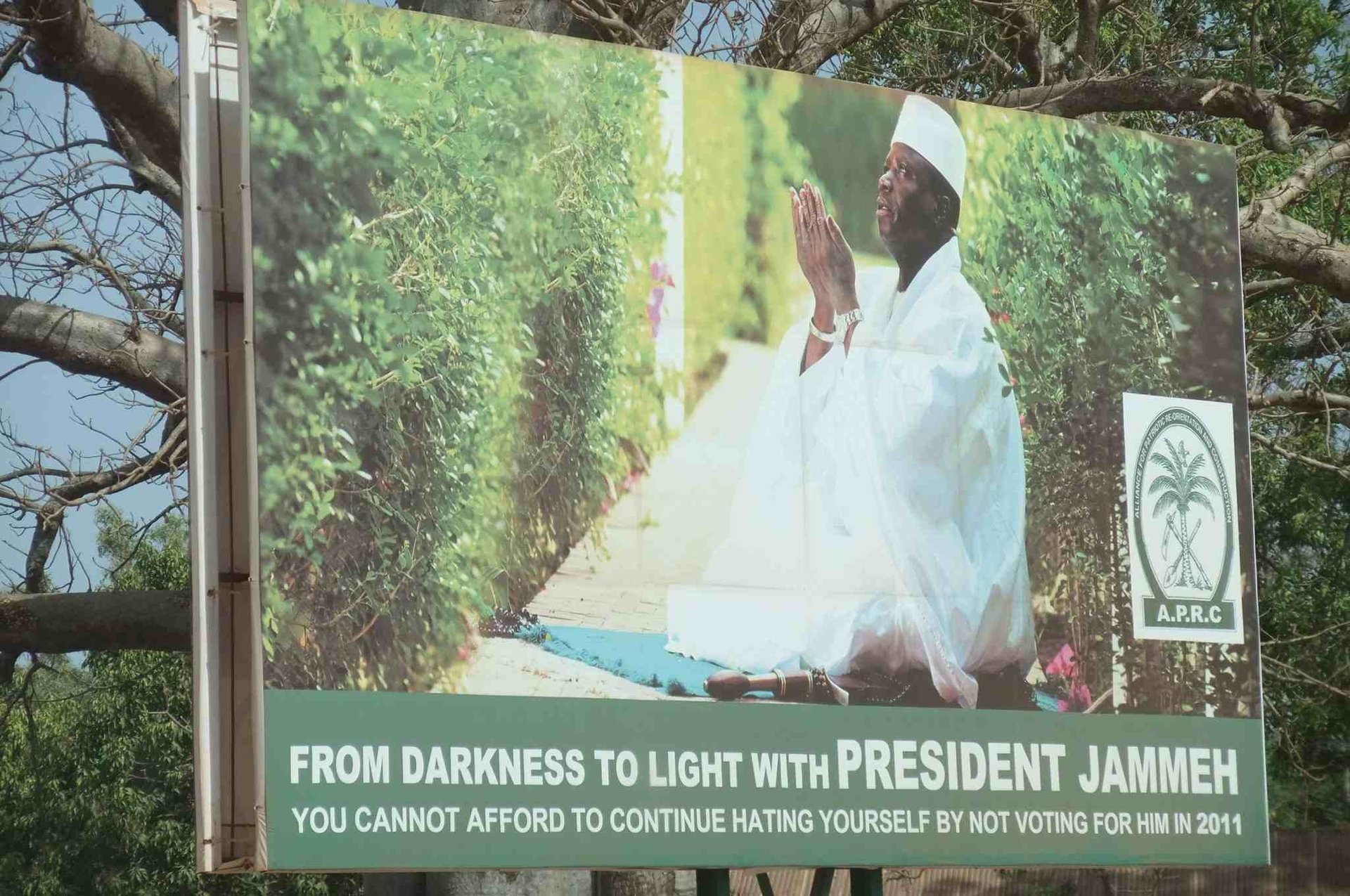

In 2011, Akino Shinagawa, a Japanese national visiting the country for work, was fascinated by Jammeh’s grandiose election campaign billboards. “I found the propaganda very cliché—this is what you would imagine to see in a country under a heavy dictatorship. I remember how scared the Gambian people seemed to be to talk about politics in public.”

While some of the claims in the posters seem over-the-top given the conditions of many ordinary Gambians. There’s an acceptance that there was some progress in Jammeh’s early years. ”In his early years, he was evil but he tried to achieve things in education and health,” says Dabo.

Ceesay notes positives during Jammeh’s reign: “He was able to achieve gender equality and empower women, also access to basic and secondary education and primary health care.” Infrastructure and roads also improved during his time, Ceesay notes.

As Shinagawa spent more time in Gambia she realized that people were not as cowed as she initially thought. “Many people never gave up their hope for change. I became convinced his regime would not last for so long. This prompted me to to take these photos.”

It’s a testimony to the oppressive feeling these billboards and posters dotted around the country must have given that as soon as it became clear he was going, ordinary Gambians took to tearing them down. ”He looted the country, actually he believed the country belonged to him and our resources were his own,” says Dabo. “I can’t wait for the day he will be prosecuted because there are many victims who are waiting for justice.”

For now, the mood is cautiously jubilant in Gambia. “I myself and everyone is so happy and proud to be a Gambian, says Ceesay. “I am optimistic that Gambia will be better but unless I witness it, I can’t be sure, because African leaders make empty promises.”